(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The protesters occupying America’s streets are rightly outraged over the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and so many others, and the chronic brutality those deaths exemplify. But their anger also reflects another malaise: the disparate impact of the coronavirus crisis on the country’s Black population.

As the pandemic spreads, it is killing and impoverishing Black people at outsized rates. This is partly because generations of discrimination have left them disproportionately vulnerable and facing a terrible choice: Put their lives on the line by going to work, or lose their livelihoods.

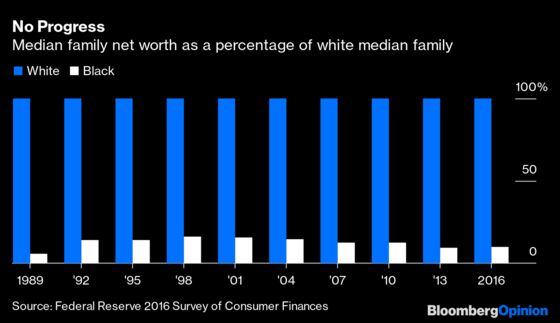

Even before the pandemic arrived, almost one in two Black people were in such precarious financial straits that they either couldn’t pay their monthly bills or would fall short if faced with a sudden $400 expense, according to the latest data from the Federal Reserve. The net worth of the typical Black family stood at just one tenth that of the typical White family, a gap that has hardly budged over the past three decades.

These underlying injustices have long demanded action. Now, they are rendering American society dangerously fragile at a time when unity is badly needed.

*****

How did race become a risk factor, so closely associated with people’s standard of living and susceptibility to a deadly pandemic? The process has by no means been natural or inevitable.

For Black Americans, 250 years of slavery were only the beginning. From emancipation through the mid-1900s, untold numbers in southern states were lynched, robbed of their land and property, or arrested, convicted and sold into forced labor — a precursor of the mass incarceration that still destroys so many Black lives. Those who fled north in the two Great Migrations of the 20th Century found themselves excluded from the government housing subsidies that created the White middle class and many of today’s suburban communities — to the point where one Detroit developer actually built a half-mile-long concrete wall to keep out a neighboring Black community. Instead, they were crowded into segregated neighborhoods, deprived of public investment and subjected to myriad forms of financial predation, including the land contracts of the 1950s and 1960s, the subprime mortgages of the early 2000s and the payday lenders, tax preparers and auto dealers of today.

Once a certain group of people has been set up to fail — once concentrated disadvantage associates them with zip codes, education, health, wealth and other characteristics — discrimination becomes pervasive and automatic. “Colorblind” policies exclude them, police profile them, employers shun them, credit algorithms reject them, all but ensuring a perpetual state of insecurity.

*****

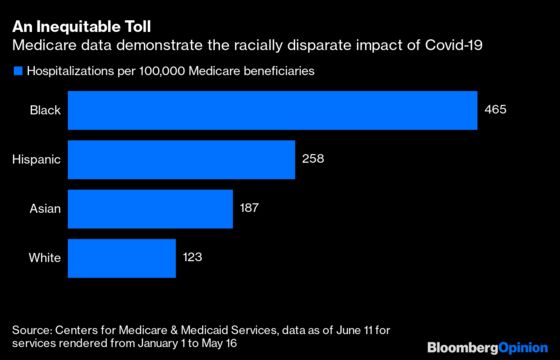

The coronavirus has made that insecurity even more deadly. National data are incomplete, so nation-wide generalizations are difficult. That said, analyses by county and age group, and in specific cities, suggest that the disease is hitting Black people much harder. Black Medicare beneficiaries, for example, have been hospitalized at a rate almost four times that of White beneficiaries, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. New York City, which as of mid-June accounted for almost a fifth of recorded U.S. Covid-19 deaths, reports that Black and Latino residents are perishing at age-adjusted rates at least twice that of their White counterparts. Similar trends have emerged in Chicago and Los Angeles.

Black workers’ roles in the job market have rendered them particularly exposed — part of what Dr. Anthony Fauci, the country’s top infectious disease expert, has called a “double whammy” of underlying health conditions and work-related hazards. They occupy an outsized share (more than 15%) of high-risk “front-line” jobs such as bus drivers, grocery-store cashiers and home health aides. They’re also less likely to be able to work from home, more likely to rely on public transportation and more likely to be employed in hard-hit service industries such as hotels, restaurants and retail stores.

At the same time, many Black Americans have been among the last to benefit from federal aid — if they benefited at all. The Internal Revenue Service distributed relief checks of $1,200 per adult and $500 per child, but struggled to track down millions of people who earn too little to file a tax return, or who lack bank accounts — groups that are both disproportionately Black.

More broadly, the pandemic is deepening the disparities that have made disadvantaged communities vulnerable. Local businesses may never recover, particularly given how hard it has been for them to access Paycheck Protection Program funds. The shift to online school is setting back kids who lack the equipment and space they need to study. And people who had no formal work to begin with are falling even further into poverty.

What to do? Let’s begin with the simple things, aimed at alleviating the immediate distress of the people most in need.

A temporary expansion of federal food stamp benefits, for example, would be an excellent way to reach those whom the Cares Act has missed, including the unbanked and the deeply poor. Emergency rental assistance could help people stay in their homes after eviction moratoriums end. More federal funds could help state and local governments reduce backlogs of people applying for emergency benefits.

It’s essential that people be able to access medical care, stay away from work when they’re sick, quarantine safely and care for their loved ones. To that end, Congress should design relief funds in a way that encourages states to expand coverage for Covid-19 related medical expenses under Medicaid. It should extend paid sick and family leave to the tens of millions of U.S. workers still not fully covered, in part by applying that requirement to companies employing more than 500 people. And state and local governments, with federal support, should provide space in dormitories or hotels for people who need a temporary place to self-quarantine or escape an infected household.

*****

Immediate aid alone, though, won’t address the original malaise: the deep inequities that divide the nation by race. That will require a much more fundamental reckoning, and a much more ambitious effort to rectify historical injustices.

First come basic rights and freedoms. The government should commit itself to gathering and publishing the data needed to recognize discrimination wherever it arises, including in credit, employment, procurement, suffrage, arrests and convictions. It should also reorient and redouble its efforts to defend civil rights: for example, by reforming the criminal justice system, eliminating disenfranchisement through voter-ID laws and roll purging, enforcing rules designed to end exclusionary neighborhood zoning rules, and requiring implicit bias training wherever its authority extends.

Second, we need to reverse the damage done. America undermines its own prosperity by shunting people of color into dead ends of concentrated disadvantage. A well-coordinated remedy for this could start with a large federal investment aimed at turning around the country’s most disadvantaged communities, using programs that have proven effective in improving health, education, public safety and employment — and gathering more evidence that will allow government spending across the country to be directed toward what works. Examples include increasing access to free Pre-K, expanding training and apprenticeships, providing incentives for lead abatement, and upgrading infrastructure to improve resilience and quality of life. Such initiatives should coincide with broader reforms, such as making affordable health care available to all and a quality public college education effectively free for the lowest-income students.

Third, we should knock down the obstacles that lock in wealth disparities. From generation to generation, it’s hard to get ahead if you lack the resources to weather a small shock, let alone to provide a boost or a backstop for your children. Yet a combination of federal policy and more subtle discrimination have excluded many people of color from the two main vehicles of wealth creation: homeownership and entrepreneurship. Here, too, there’s no single fix. Building more low-income housing for purchase will increase supply and reduce prices. Connecting the unbanked with free or fairly priced accounts, and updating credit-scoring models, will make more people eligible for loans. Enforcing fair-lending laws and supporting Community Development Financial Institutions, which focus on underserved communities, can ensure that people get the credit they qualify for. Providing down-payment assistance, and allowing federal housing vouchers to be used for mortgage payments, can help people build equity. And providing entrepreneurs with targeted microloans, mentorship networks and effective one-stop shops to help access credit, navigate bureaucracy and bid for government contracts can help them to start and grow businesses.

The crucial elements of this effort must be persistence and care, an overarching determination to identify and expand the measures that demonstrably help. The benefits should flow broadly — to Black Americans, to all people who find themselves on the wrong end of discrimination and, ultimately, to the entire country, by allowing more Americans to realize their full potential.

No doubt, the pursuit of such an agenda will be a monumental national undertaking. Yet if this crisis has demonstrated anything positive, it is that Congress is capable of agreeing on unprecedented measures, and mustering trillions of dollars, when facing the abyss. The profound divisions in American society are even more threatening than the pandemic that has exacerbated them. They deserve to be taken no less seriously.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Whitehouse writes editorials on global economics and finance for Bloomberg Opinion. He covered economics for the Wall Street Journal and served as deputy bureau chief in London. He was founding managing editor of Vedomosti, a Russian-language business daily.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.