Question Everything You Know About Bonds Versus Stocks

What is clear is that stocks’ sagging performance over the last two decades is a challenge to three burgeoning investing theories.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- While everyone was consumed with the coronavirus, something remarkable happened in U.S. markets: When March ended, bonds had outpaced stocks over the last two decades.

That’s right. The Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index beat the S&P 500 Index by 0.3 percentage points a year over the last 20 years through the first quarter, including dividends. As it turned out, investors would have made more money and lost less sleep if they had just stuck with boring old bonds.

It’s not supposed to work that way, as every investor has been told tirelessly. Bonds are for stability and stocks are for growth. The price of stability is lower returns relative to stocks, and the price of growth is higher risk relative to bonds. That trade-off between stocks and bonds is known in technical parlance as the equity risk premium.

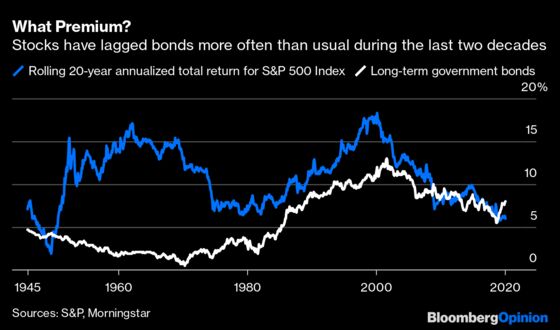

The premium was once shockingly reliable over long periods. From 1926 to 1999, the longest period for which numbers are available, long-term government bonds beat the S&P 500 just 2% of the time over rolling 20-year periods, counted monthly. And all those victories were clustered around a short period from 1948 to 1950, the aftershock of stocks’ tumult during the Great Depression.

But the equity risk premium has been less bankable since then. Bonds have beaten stocks 26% of the time over rolling 20-year periods ending in 2000 or later. While it’s not easy to draw neat causal lines around markets, there are some obvious contributors to bonds’ recent success. The historic decline in interest rates from record highs in the 1980s to record lows today has bolstered bonds. Also, stocks stumbled on an unusual succession of extreme shocks, beginning with the bursting of the biggest stock market bubble in U.S. history in 2000, followed by a near collapse of the financial system in 2008 and now a global pandemic that has shut down the economy.

What is clear is that stocks’ sagging performance over the last two decades is a challenge to three burgeoning investing theories. The first is that the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings, or CAPE, ratio, once a vaunted barometer of future stock returns, has lost its predictive power. From 1881 to 1999, the average CAPE ratio for U.S. stocks hovered around 15, according to numbers compiled by Yale professor Robert Shiller. When the CAPE drifted meaningfully higher during that period, subsequent stock returns tended to be lower than usual, and vice versa.

Then the CAPE seemed to break down. After the fierce bull market of the late 1990s, the CAPE stood at a record high of 44 when 2000 began, an unmistakably bearish signal. The S&P 500 was cut roughly in half during the ensuing market crash, but the CAPE bottomed at 21 in early 2003, still well above its historical average. Nevertheless, a new bull market took hold and, except for a brief period around the financial crisis, the CAPE has been higher ever since.

Those who waited for the CAPE to dip back below its historical average missed the bull market that followed the financial crisis, by some measures the second longest on record. And they’re still waiting. Not even the coronavirus has been able to subdue the CAPE, which now stands at 23.

Many investors have concluded from the last two decades that the CAPE has become more noise than signal. That now appears to be hasty. In addition to losing to bonds, the S&P 500 has returned 4.8% a year over the last 20 years through March, which is roughly half its long-term average. Perhaps the CAPE’s warning rang true after all.

A second and related theory is that intervention by central bankers is a boon for stocks. When the dot-com bubble popped in 2000, the Federal Reserve jumped in to dampen the fallout by gradually lowering short-term interest rates to 1% from 6.5%, a level not seen in the U.S. since the 1950s. Subsequent interventions have been more brazen. The Fed cut rates to near zero and purchased roughly $4 trillion worth of bonds during the financial crisis, the most ambitious stimulus effort in the Fed’s history. And in recent weeks, the Fed cut rates to near zero again and pledged to prop up bond markets, expanding its balance sheet to a record $6 trillion.

Many investors credit the Fed for keeping stock valuations elevated over the last two decades. Whatever one thinks of the wisdom of those moves, however, the results haven’t been a windfall for stock investors.

The third theory is that value investing is dead. While value stocks have historically paid a premium relative to growth, U.S. growth stocks have beaten value over the last 12 years and have held up better during the current downturn. For many investors, it’s a sign that value stocks can no longer be expected to pay. But if 12 years of underperformance for value relative to growth means that the value premium is dead, what does 20 years of underperformance for stocks relative to bonds say about the equity risk premium?

Not much, apparently. Investors have handed a net $36 billion to U.S. equity exchange-traded funds since the S&P 500 tumbled from its peak on Feb. 19, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. Still, it’s early days. With the CAPE perched at 23, more than double its financial crisis low, the market appears to be signaling that the coronavirus shutdown will be short-lived. But if it proves otherwise, bonds are likely to extend their lead over stocks, and investors may have to second-guess some newly embraced ideas.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.