QE Works. It’s Just Not a Slam-Dunk Recession Stopper.

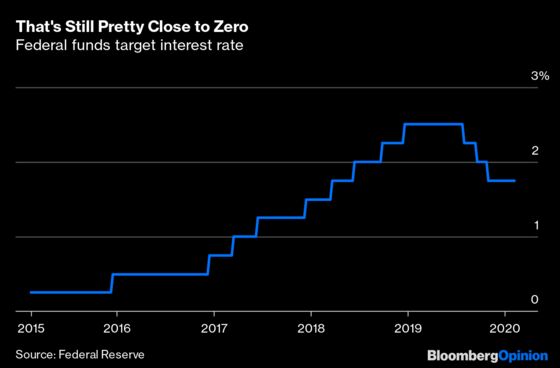

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The U.S. economy seems to have reached a comfortable equilibrium, with low unemployment and steady growth. But if and when a recession comes, the Federal Reserve is going to have to fight it. The traditional tool for stabilizing the economy — interest rate cuts — won’t do much because rates already are so close to zero that further reductions probably won’t make much difference:

Forward guidance — promising to keep rates low for a long time after a recovery — also probably isn't going to be very effective. Who believes what the Fed says today about what it will do in the distant future? And how much difference would that even make for the plans of the typical company or consumer?

That leaves some kind of quantitative easing — mainly purchases of financial assets such as long-maturity bonds — as the main option. But how well would quantitative easing work? Economists have struggled to answer this question. It’s not even clear how well QE worked last time. All we know is that a lot of QE happened and that a recovery eventually followed, but that doesn’t mean the former necessarily caused the latter.

Theoretically, there are a number of ways QE might have helped the economy during the Great Recession. One way is portfolio rebalancing: QE lowers interest rates on the assets similar to those that the central bank buys, which might push investors to seek to maintain their expected returns by pouring money into riskier assets such as stocks and high-yield bonds. This might make it easier for companies to borrow and invest. QE also might be useful because the Fed effectively acts as a lender of last resort to distressed borrowers; this was the case when the central bank took toxic real-estate-backed bonds off of banks' balance sheets after 2008. QE may also decrease leverage ratios for banks, allowing them to make more loans.

Theory alone is unlikely to tell us which, if any, of these channels is important. The models that are used to derive these predictions usually involve many unrealistic assumptions, so there’s no one model that obviously corresponds to reality. Instead, the best economists can do is assess the impact of QE on things like bank lending and corporate borrowing costs, assuming that things would work similarly in a future recession.

One way to assess QE is to look at how financial markets and the economy react to announcements of asset purchases. This is how economists typically identify the effect of standard monetary policy.

Drawing connections between Fed decisions and economic effects is harder than it sounds. QE announcements may have been anticipated by markets, so assessing the impact of a new policy requires making some assumptions about how surprised markets really were. Usually, economists do this by looking at how market prices — which give a good indication of investor expectations — react to Fed decisions over the course of a few minutes.

Another problem is that it’s always questionable whether a QE announcement has an effect because of the QE policy itself or because it signals a more dovish Fed attitude. In a 2017 paper, economist Eric Swanson tried to deal with this by comparing QE announcements with forward-guidance statements. He found that the former had a much bigger effect on corporate bond yields than the latter, suggesting that QE convinces the market that companies are going to be able to borrow more cheaply.

In a recent paper, economist Daniel Lewis compared the reaction to QE and other monetary-policy announcements with other asset-price movements on the same day. (This method also allows him to look at the differences between various rounds of QE, because not all QE is created equal.) Like Swanson, he found that asset purchases had a big effect on corporate borrowing costs.

Of course, there’s always the chance that asset prices react to QE announcements in the short term, but that these reactions fade over time. Lewis found that the effect persists to the end of the day, but months or years are a different matter. Swanson found that changes in asset prices persist for as long as four months after an asset-purchase announcement, though this requires making various additional assumptions.

These exercises show how hard it is to get solid, conclusive proof in macroeconomics. Even if all of these researchers’ assumptions hold, certainty is elusive; lower borrowing costs might not always make companies invest more. And changes in the economy since the early 2010s might make a future recession a different story. For example, if QE worked mainly by taking toxic housing-backed assets off of shaky banks’ balance sheets, it won’t be very effective in a future recession that doesn’t involve banks loading up on garbage bonds.

Although these papers (and others that found similar results) don’t make a slam-dunk case for QE’s effectiveness, they represent the slow accumulation of evidence in favor of the policy. In the next recession, QE will be — and should be — the Fed’s main line of defense.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.