Puerto Rico’s Messy Bankruptcy May Get Even Messier

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Even for a longtime observer of the U.S. municipal-bond market, it has been tough to keep up with the play-by-play of Puerto Rico’s unprecedented bankruptcy.

After all, it has already been more than four years since the commonwealth’s governor first declared its debt unpayable and said investors should prepare to sacrifice. Congress passed a law called Promesa in 2016 that allowed Puerto Rico to seek bankruptcy, and in May 2017 it did just that. A federal board overseeing the island’s finances has been gradually working with various stakeholders to reach an agreement. On Sept. 27, the board took what appeared to be a crucial step by releasing a full-fledged restructuring plan that laid out how much bondholders and retirees stood to lose.

In an ordinary bankruptcy, it would now be a straightforward question of whether pensioners and creditors agree to the terms and what tweaks might be needed to get to the finish line.

But this is Puerto Rico. Rather than approaching the endgame, this week could wind up dealing a setback to the foundation of the restructuring process.

The U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral arguments on Tuesday in a case brought by Aurelius Capital Management that challenges the constitutionality of the federal oversight board. The issue revolves around a provision known as the appointments clause, which specifies how “officers of the United States” are selected for their positions (nominated by the president, confirmed by the Senate). When Congress enacted Promesa, it stipulated that the oversight board was an entity created within the commonwealth and therefore not part of the federal government, so it didn’t have to appoint members in the usual way.

Promesa states that neither Puerto Rico’s governor nor its legislature can control or supervise the oversight board. The elected officials also can’t enact statutes that would hamper the board’s ability to work through the bankruptcy. Without getting into strict legal arguments, it does seem somewhat odd for a “territorial entity” to have no accountability to the leaders of the same territory.

A federal district court dismissed that argument, basically stating that Congress has sweeping authority when it comes to U.S. territories and can structure governmental entities and appoint officers accordingly.

Yet that hardly convinced the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. “The district court was certainly correct that Article IV conveys to Congress greater power to rule and regulate within a territory than it can bring to bear within the fifty states,” the judges wrote in their opinion. However, “we do not view these expanded Article IV powers as enabling Congress to ignore the structural limitations on the manner in which the federal government chooses federal officers.” The oversight board members, they said, are indeed U.S. officers. And because they weren’t nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate, the current board violates the appointments clause.

Aurelius, which was famously part of a group of holdout creditors that refused to reach a deal during Argentina’s debt crisis, asked the court to invalidate everything the oversight board has said and done so far. After all, its members were unconstitutionally appointed.

But even the appeals court refused to go that far:

“We fear that awarding to appellants the full extent of their requested relief will have negative consequences for the many, if not thousands, of innocent third parties who have relied on the Board's actions until now. In addition, a summary invalidation of everything the Board has done since 2016 will likely introduce further delay into a historic debt restructuring process that was already turned upside down once before by the ravage of the hurricanes that affected Puerto Rico in September 2017.

...

Our ruling, as such, does not eliminate any otherwise valid actions of the Board prior to the issuance of our mandate in this case.”

Even if the Supreme Court agrees with this ruling, it might not be as damaging as it could be for the board’s progress: After the appeals court ruling, President Donald Trump opted to nominate the same seven members now serving on the board for Senate approval.

But then there’s the restructuring proposal itself. Released last month, it seems like a lesson in shared pain. It would cut the commonwealth’s debt and other liabilities by 60%, to $12 billion from $35 billion. As for government employees, those with pensions that pay less than $1,200 a month wouldn’t be impaired, while those earning more than that (about 40% of retirees) would have their benefits cut by 8.5%. Those losses could be restored if Puerto Rico grows faster than anticipated. For now, the plan would reduce the $54.5 billion pension obligation to $45 billion.

Favoring pensioners over bondholders is nothing new. But perhaps the most interesting part of Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy plan is how the board is continuing to push the idea that it can simply wipe out $6 billion of general obligation bonds from 2012 and 2014 because selling them in the first place breached the island’s constitutional debt limit. I wrote in January about how that outcome could prove critical for the next big muni-market default, wherever it may be.

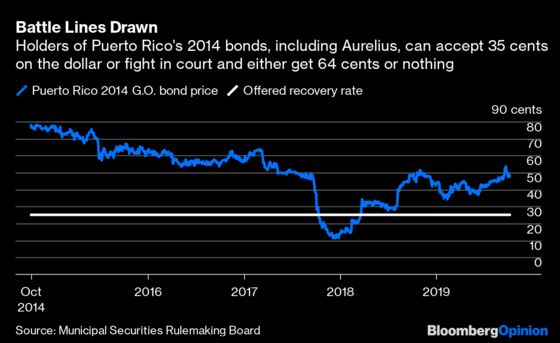

The board clearly thinks its threat has merit, judging by the paltry recovery rates it’s offering to investors. While G.O. bonds issued before 2012 would recoup 64 cents on the dollar, 2012 and 2014 vintages would get just 45 cents and 35 cents, respectively. If holders of 2012 and 2014 debt turn down the deal, they can try to fight for the same recovery as the rest of the bonds in court, though if they lose they’d get wiped out entirely. The stakes are high: The 2014 Puerto Rico debt is still trading at about 60 cents on the dollar, and Aurelius is one of the primary owners.

All the while, the commonwealth has paid about $400 million in legal and advisory fees, according to an analysis from Debtwire. The island’s population decline continues, with about 133,500 people moving from Puerto Rico to the mainland in 2018, according to census data. Last week, protesters gathered in front of the governor’s mansion in San Juan and what they thought were the private homes of oversight board members to voice opposition to the cuts to some pensions. Puerto Rico Governor Wanda Vazquez said she didn’t support reduced benefits but wanted the board to finish “as soon as possible.”

Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy has always been messy, but years later, it seems just as chaotic, if not worse. Assured Guaranty Ltd., in an Oct. 2 statement, said it doesn’t support the board’s restructuring plan though noted that “an end to the Puerto Rico debt crisis is in sight.” All it would take, the bond insurer said, is “consensual resolutions and accurate financial data, and not by attempting a cramdown on investors who have supported the island for decades.”

In other words, Puerto Rico doesn’t seem anywhere close to the end of this unfortunate chapter in its history.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.