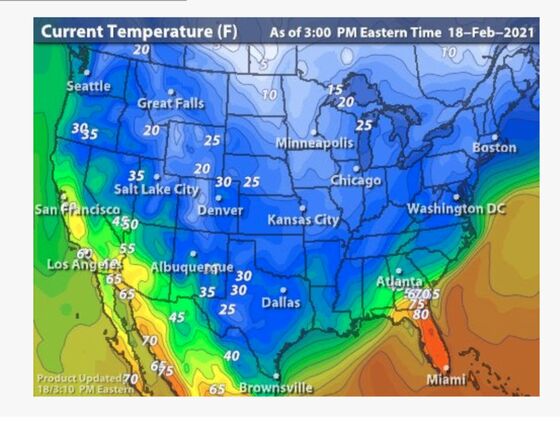

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Storms and frigid weather have walloped the U.S. this February. Millions in Texas lost power for days — in homes that aren’t prepared for the sort of cold we saw last week:

Come summer, those of us up north will likely be sweltering in temperatures that our un-air-conditioned houses weren’t built for. All of this taxes the power grid, which faces additional stress from climate-change induced superstorms.

Maybe it’s time to invest in some upgrades to our homes.

Home renovation has been a bright spot in the U.S. economy during the pandemic, with homeowners splashing out on home offices, new patios, even family theaters — and sending lumber prices soaring. But with more extreme weather on the way, more homeowners should be thinking about the home improvements you don’t see: insulation and power generation.

When we bought our first house, my husband and I saw only the potential of the wisteria-covered 1864 New England colonial. We didn’t see the boiler that was about to break; the total lack of insulation; or the drafty windows that, if not 19th-century vintage, were pretty darn close.

We learned fast. And, fortunately, our new house turned out to be just down the street from the Boston Globe handyman columnist, Rob Robillard, a contractor and carpenter. After peppering him for advice, the money we’d set aside for cosmetic upgrades — like renovating the jungle-themed bathroom, complete with a Kipling poem painted on the walls — was immediately reallocated to blow-in insulation, double-paned windows and a new furnace.

These upgrades may not have the Zillow appeal of a copper soaking tub, but they’re investments that pay off in lower heating and cooling costs, and make houses a lot more livable in a changing climate.

If you’re willing to do a wholesale renovation, tons of stuff can be done to improve a home’s energy efficiency. But most of us aren’t eager to start tearing down walls. So I called our old neighbor and asked him how he’d upgrade a house for extreme weather without making too much of a mess in the process.

Robillard says the easiest place to start is at the top: Insulate your attic. Homeowners tend to focus on walls and windows, but most heat is lost through the roof, because heat rises (duh). “This is definitely where you’ll get the most bang for your buck,” he says.

And before insulating the attic, check for air leaks. If there are holes drilled in the wall for power lines, or leaks around the chimney, seal those first, then insulate. Hire a professional or rent an infrared imaging camera from the local big box hardware store for about $50; on a cold day, the air leaks should be immediately obvious.

To insulate walls, blow-in cellulose insulation is relatively cheap and easy. Basically, specialists drill holes in the outside of the house, pump a bunch of shredded, chemically treated newspaper into the holes, and then seal them up again.

On that 1864 colonial, which was about 1,700 square feet, insulating the exterior walls cost roughly $4,000. After state energy incentives, the cost to us was only about $2,500. It probably saved us about $450 a year in heating costs, or enough to pay for itself after five years. One other benefit: Insulation completely stifled the road noise we’d gotten used to hearing.

Consider storm windows (say, $75 each) before replacing the entire window ($300-$500 each, before installation), especially if the existing windows are relatively new. (And don’t forget the storm doors, says Robillard.) But if you’ve got very old windows – the kind that rely on a rope, pulley and counterweight – replace them. The hollow cavities that house the counterweight are basically huge, heat-sucking voids. Replacing ancient windows will also improve the home’s resale prospects.

In addition to saving on heating and cooling costs, these modest insulation improvements can often net tax savings, rebates or other government-subsidized savings.

Climate change isn’t bringing only hotter summers and colder winters. It’s also bringing more-violent storms, making power outages a fact of life in many places. These aren’t just dangerous or unpleasant – they can be expensive, if lost power leads to frozen pipes and water damage. If like the average American, your home accounts for roughly a third of your total net worth, installing a generator should be seen as a form of insurance.

You have three options: cheap, expensive and more expensive. The cheap option is a small, portable generator that runs on gas or diesel. It will cost about $800-$1,500 at Home Depot, and you might need an electrician to install an outdoor outlet to let it connect to the house. A tankful of gas will get you about 6-8 hours of energy, just enough for a few hours of power here and there in an emergency. (Robillard suggests safely storing extra gas in case you need it.) This is a good option if money is tight and if you don’t mind fumbling around in the dark with tanks of gasoline.

The expensive option is a whole-house generator that will cost between $3,000 and $9,000 before any installation costs. These generators are wired to a house and connected to a source of fuel – like a propane tank – and switch on automatically if the power fails. If your town has had outages lasting multiple days, or you simply aren’t a very handy person, it’s a worthy investment.

Our current house has one – the previous owner was often away, and installed it to protect her two enormous white cockatoos. What seemed like overkill for two birds has turned out to be incredibly convenient and reassuring for two humans. We can go for days without power from the grid, and I don’t have to do anything to make it happen.

The more-expensive option is a solar-powered home battery like the Tesla Powerwall. These store power from solar panels on your roof. They help defray the costs of fossil-fuel powered electricity and act as a back-up battery for a home in the event of an outage. Total costs (including installation) start around $12,000, but that’s assuming the house already has solar panels. If not, those have to be installed, too.

While solar is getting cheaper all the time, it can carry hidden costs. For example, you need to make sure the roof can handle the additional load of the panels. Even thinking about roof work is expensive.

Another downside: House batteries generally don’t have enough oomph to cover all your energy needs, so in the event of an outage, you’ll have to make tradeoffs. On the other hand, I hear the feeling of superiority you get from owning a Tesla-powered house is priceless. And if there’s a way to make the most boring of home renovations sexy, I’m sure Tesla has figured it out.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Sarah Green Carmichael is an editor with Bloomberg Opinion. She was previously managing editor of ideas and commentary at Barron’s, and an executive editor at Harvard Business Review, where she hosted the HBR Ideacast.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.