California Allows Uber's Gig Economy to Live Another Day

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Defying expectations, California voters have approved Proposition 22, which exempts so-called gig economy companies — companies like Uber Technologies Inc. and Lyft Inc., as well as grocery delivery services — from a state law that requires them to classify their workers as employees. Instead, ride-hailing and food-delivery app companies will be able to keep their workers as independent contractors, meaning those workers get fewer benefits and won’t be required to earn minimum wage.

The ballot measure is sure to dismay advocates of higher labor standards. Strangely, it comes at a time when many states and cities are raising their minimum wage and requiring companies to give employees various other benefits. While the result might be simply a function of a well-run corporate ad campaign, it might also reflect a general anxiety about the future of cities. Gig economy services aren’t just a source of extra work; they’re coming to be an essential part of modern urban economies. And with those urban economies under threat, voters may be reluctant to jeopardize the fragile equilibrium.

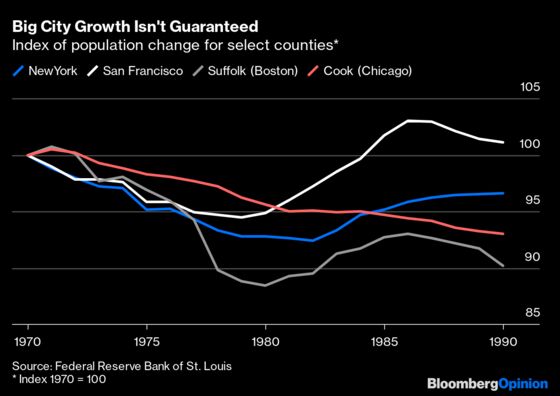

In the 1970s, many big U.S. cities lost population as workers fled to the suburbs:

The phrase “inner city” became synonymous with poor, neglected neighborhoods. But starting in the 1990s, the trend reversed. As economist Enrico Moretti documented in his book “The New Geography of Jobs,” many big cities became Meccas for educated workers in newly ascendant knowledge industries like technology, finance and biotech. These cities, which included coastal metropolises like San Francisco and New York City and Sunbelt hubs like Houston and Atlanta, benefited from what economists call clustering effects. With large concentrations of employees and workers, it was easy to find a job or an employee in these clusters. And everyday interactions between knowledge workers resulted in the spread of useful ideas from company to company.

Thanks to clustering, it became difficult for workers to resist the pull of superstar cities. High earners streamed back into urban cores. In due time, apps like Uber, Lyft and Instacart arose to cater to this new urban workforce. Since U.S. cities have been famously unwilling to invest in trains, ride-hailing apps emerged as a workable substitute, enabling upper-middle-class workers to get around San Francisco or Seattle or San Diego quickly without breaking the bank.

The superstar-city boom may have ground to a halt. Concerted efforts by local homeowners, aided by some misguided progressive groups, have hindered most cities in developing new housing, driving up rents to near-intolerable levels and slowing the population influx. Then the Covid-19 pandemic struck. Coronavirus pushed knowledge industries to make their workforces remote, driving mass adoption of technologies like Zoom. That may spark a long-term shift, in which tech and finance companies require only a portion of their workforces to be on-site going forward. Already rents are falling fast in San Francisco and many other high-cost cities:

This threat of knowledge-worker exodus means that superstar cities’ clustering effects no longer look so invincible. If tech employees can keep only a skeleton workforce in high-cost urban cores and send the rest out to cheaper locales — perhaps to newly densified inner-ring suburbs that offer many of the benefits of city life with fewer of the costs — then it means big cities like San Francisco can no longer rely on inevitable economic forces to keep their tax bases growing. Instead, they may have to once again fight to keep upper-middle-class workers in town, as they did before the 1990s.

And that means that canceling the gig economy would be a dangerous move. The push for higher labor standards is popular and important, but if it ends up pricing Uber, Lyft and other gig services out of reach for the upper middle class, it could make urban life less attractive for that crucial population. Without the ability to take moderately cheap rides around town, many knowledge workers might go remote, leaving cities with lower tax revenues.

Of course, cities could remedy this if they built dense, efficient networks of trains of the type that exist in New York City and in many Asian and European cities. But with construction costs much higher in the U.S. than in those other countries, and with anti-density forces firmly entrenched in local politics, there doesn’t look to be much chance of getting a Tokyo-style subway system in San Francisco or Los Angeles.

So in lieu of public transit, California voters may have decided to stick with cheap ride-hailing services as a second-best option for keeping taxpayers in town. Gig workers will continue to suffer a precarious existence, but the superstar-city model may live another day.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.