Soccer Will Never Be Anything More Than a Vanity Play

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Owning a soccer team has long seemed a mug’s game — little more than a vanity project for the errant super-rich.

Until recently, that is. A new breed of owners with backgrounds in U.S. private equity is seeping into the beautiful game, particularly England’s Premier League, where club valuations have soared. Greater financial certainty has made teams a more appealing investment. But when it comes to seeking an exit, the same risks prevail.

A quarter of the Premier League’s 20 teams now have an owner in private equity. That ranges from Silver Lake’s 10% stake in City Football Group Ltd., the parent company for Manchester City Football Club, to Fortress Investment Group founder Wes Edens’s co-ownership of Aston Villa Football Club. Even more are circling. The Wall Street Journal and Financial Times reported last month that Todd Boehly, whose Eldridge Industries LLC owns a number of media companies and part of the Los Angeles Dodgers, made a failed bid to acquire Chelsea Football Club.

Owners are generally loath to discuss why they invest in a given soccer club. They prefer to talk about a team’s unrealized sporting potential than the ability to wring more money out of its fans. But the business logic looks pretty straightforward: apply some know-how to boost commercial revenue, particularly in Asia and the U.S., and hope that income from broadcast rights continues to soar.

The problem in soccer is that more revenue doesn’t always mean more profit. Take Manchester United Plc. The English giant’s sales ticked steadily upward over the past decade, rising 75% between 2009 and 2019 to 627 million pounds ($821 million). Profit has been harder to depend on, swinging from 5.3 million pounds in 2009 to a 48 million-pound loss the following year. The team, whose roster boasts French World Cup winner Paul Pogba and England defender Harry Maguire, posted a somewhat measly 19 million pounds profit in the last fiscal year.

While admittedly coinciding with a period of lackluster on-field performances, the team’s shares have underperformed the S&P 500 since their 2012 listing.

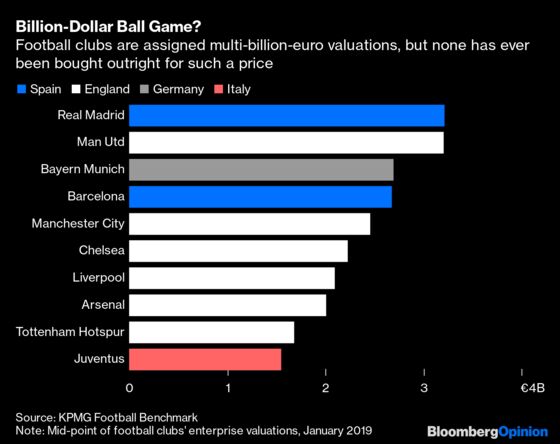

It makes investing in a soccer team that’s already near the top of the league table a difficult proposition. Chelsea owner Roman Abramovich is reportedly seeking 3 billion pounds for the club, which has won five league titles under his ownership. Given the profit it generated last year, that would mean annual returns of little more than 2%. And prospects for making more money off team jerseys, gear or specialized fan services are more limited at those major teams that have already spruced up their offerings as their sporting fortunes grew.

The greater opportunities are to be found in smaller clubs with unrealized potential. Aston Villa is a prime case in point. When Edens and the Egyptian billionaire Nassef Sawiris bought a 55% stake in the team for about 30 million pounds in 2018, they were acquiring a distressed asset scrapping for promotion from England’s second tier. But the risk was low given the upside for one of the biggest teams in England’s second-largest city, Birmingham. Just two years earlier the club had changed hands for twice that much money.

So far, the gamble has paid off after Villa secured promotion last year. Even after spending more than 100 million pounds on player transfers in an effort to fend off immediate relegation, Edens and Sawiris can expect the club to be valued at as much as five times that outlay if the team cements its Premier League status. Teams with a similar-sized stadium, fan base and history such as West Ham United FC, Leicester City FC and Everton are valued by KPMG at between 500 million euros and 600 million euros. So the worst-case scenario for Edens and Sawiris is that they perhaps lose 150 million pounds between them. Best-case, they can make a profit topping 400 million pounds. That’s a healthy risk-return profile. (When hedge fund titan David Tepper paid $2.3 billion for the NFL's Carolina Panthers in 2018, he did so safe in the knowledge the team (and therefore his income) would never be subjected to the vicissitudes of relegation to a lower league.)

In essence, it’s easier to justify acquiring a smaller, underperforming soccer club than a team already in the upper echelons. Crystal Palace and West Ham, two other clubs with PE investors, fit that profile. But while a theoretical enterprise value is all well and good, realizing that value by selling a team onto a new buyer can be a harder proposition. If commercialization has been optimized, what levers does a new buyer have to generate more value beyond the hope that broadcast revenues continue to trend upwards? Just ask Mike Ashley, the retail billionaire who has been trying to sell Newcastle United FC for more than a decade. Or Jim Ratcliffe, the chemicals billionaire who passed on the opportunity to buy a number of Premier League clubs, telling the Times of London recently that he “never wants to be the dumb money.”

For all of the professionalization of how soccer clubs are run, the implication is clear: Ultimately, the best way to secure the returns that private equity investors expect is to sell it to someone with cash to burn who is more interested in status than a return on investment. And that’s much the way it’s always been.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Melissa Pozsgay at mpozsgay@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Alex Webb is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Europe's technology, media and communications industries. He previously covered Apple and other technology companies for Bloomberg News in San Francisco.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.