Priti Patel Is Going to Make Europe’s Migrant Crisis Worse

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Dangerous migrant crossings from France to Britain have reached record levels this year. U.K. Home Secretary Priti Patel promised repeatedly to solve the problem, but her plan to use U.K. border forces to push back small boats trying to cross the Channel has not worked and faces several legal challenges.

Now, with the tragic drownings of at least 27 young migrants, after calls for rescue were apparently ignored by both French and British coast guards, the public has noticed. A recent opinion poll by YouGov showed that four in five Brits rate the government’s handling of the crisis poorly; even three-quarters of Conservatives are unimpressed.

Crucially for the government, though, polls still show strong support for the draconian approach to migrants that Patel has been pushing. (This drops among younger people.) In July, the government introduced a radical overhaul of the asylum system in its Nationality and Borders Bill, sponsored by Patel. The bill, which could get its final vote in the House of Commons as early as next week, would increase the thresholds for proof required to gain refugee status, make it easier to deny legal protection to refugees, change the appeals process and criminalize the majority of those seeking asylum.

In other words, if the goal was to prevent deaths by drowning in the English Channel and create an asylum system that is both humane and fair, this bill is likely to achieve the opposite.

The bill has been roundly condemned by charities, human rights organizations, academics and even the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Its measures are variously performative, unworkable or contravene Britain’s own international commitments. The U.K. Law Society says its likely to “damage access to justice” and is incompatible with international law.

The most obvious way the bill seeks to stop illegal migration is by differentiating between those who arrive by “safe and legal” routes and those who chance the Channel. The former are fine, the latter are criminals. Some 80 amendments were tacked on to the proposed legislation on Wednesday, just after MPs had scrutinized the bill in the committee stage of the process.

Of course, that first door is pretty much bolted shut. Regulated routes for resettlement account for only about 4% of all asylum seekers globally, says Daniel Sohege, director of the pro-bono consultancy Stand For All and a specialist on international refugee law. In the U.K., those legal routes were closed during the pandemic.

Which means that the bill criminalizes migrants for doing the only thing they can to have a chance at asylum: “Any person who enters or attempts to enter the United Kingdom without legal authority shall be guilty of an offence.” Those found guilty could face up to 12 months in prison.

The bill broadens the existing definition of arrival without permission in a way that means asylum seekers could be prosecuted for reaching U.K. territorial waters before landing on British soil, says Sarah Overton, a researcher at the U.K. in a Changing Europe. That is likely a breach of Britain’s obligations under the UN Refugee Convention.

Some measures in the bill are so impractical that their presence seems designed for political signaling — for example, the idea of farming out migrants to a “designated place” for offshore processing. Denmark passed a similar law and has struggled to find countries willing to house the applicants. The U.K. has no existing agreements for doing so. It’s also an expensive way to handle asylum claims and likely to face legal challenge.

Patel says the new system is “fair but firm.” Firm sounds like a well-meaning school teacher. But the U.K’s treatment of asylum seekers rates poorly at every stage. New figures show almost 88,000 people are waiting for their asylum claim to be decided; less than 20% of applications are processed within the six-month goal set by the Home Office.

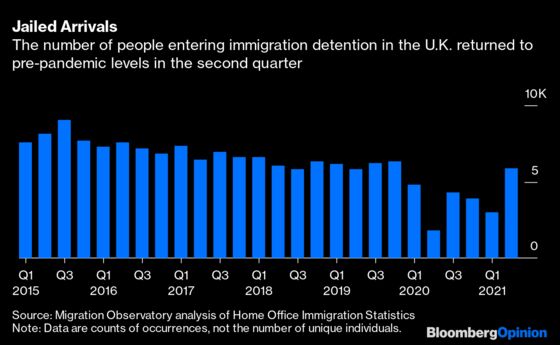

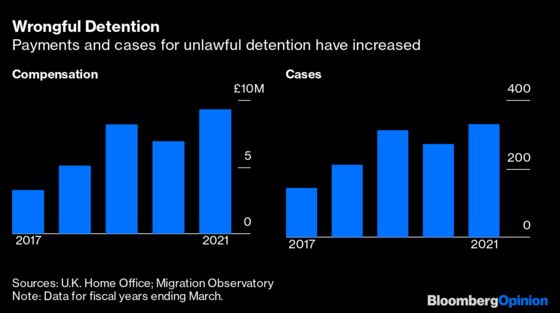

A UN Special Rapporteur said in 2018 that “destitution is built into the asylum system” in Britain, while an independent inspection of two asylum detention centers found an environment that was “impoverished, run-down and unsuitable for long-term accommodation.” The Home Office has been ordered by the courts to compensate increasing numbers for wrongful detention.

Anything that prevents people from drowning in the hopes of reaching freedom would be something to cheer. But efforts such as the Nationality and Borders bill are likely to encourage increasingly dangerous journeys and lead to more deaths, says Lucy Mayblin, a lecturer at Sheffield University. Sohege says the bill actually makes it harder for refugees to escape the grip of people traffickers once in the country.

On Wednesday, Parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights urged the government to change tack and prioritize safety at sea. Pushbacks and other measures “will not deter crossings,” the Committee wrote. “Current failures in the immigration and asylum system cannot be remedied by harsher penalties and more dangerous enforcement action.”

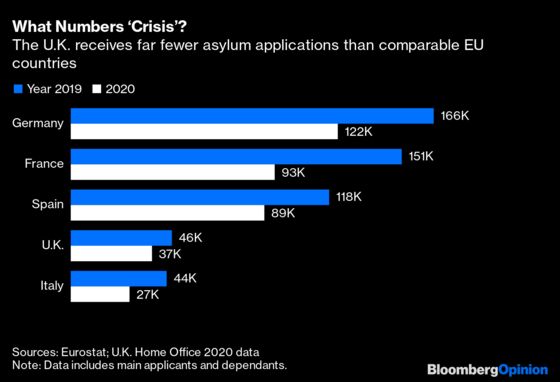

Though you’d never know it from the tenor of debate in Britain, there is no real migrant crisis in the country in terms of numbers. The U.K. ranks 17th in the European Union in asylum applications per capita. Some 64% of applications are successful, and about half of the unsuccessful applications are granted on appeal. While there are some migrants who are trying to improve their economic circumstances, the majority are actually fleeing a living hell.

Most people of Eritrea, the women in Afghanistan, and those in Sudan and Syria would be eligible for asylum should they find their way to lands where they can claim it. The vast majority don’t. Only 1% of the world’s refugees end up in Britain.

And yet, in Britain and elsewhere, immigration ranks high on lists of people’s concerns and featured heavily in the 2016 Brexit vote. The fact that asylum seekers are denied the right to work only makes them seem less desirable, especially to many who already worry about strained public services and rising taxes.

Yes, any discussion of migration has to acknowledge that there are limits to what a country can take. But with this new bill, the government is reinforcing a narrative that sees migrants as either criminal or burdensome.

It wouldn’t have to look far for examples of the contrary. Education Secretary Nadhim Zahawi accepted an award recently by noting his own remarkable journey. “How did a boy from Iraq end up on these shores without a word of English at the age of 11 and become the Secretary of State for Education,” he mused. “This is the greatest country of the world, my friends.”

It’s hard to go from celebrating Zahawi’s opportunities to condoning Patel’s new law without serious whiplash. Patel — whose own parents would likely have been kept out of the country under her new law — is right that there are no easy answers when it comes to migration. But as the new bill shows, she’s fine sticking with the easy way out.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.