Powell and the Fed Have Zero Control Over the Long Bond

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Day two of Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell’s congressional testimony was much like the first. He reiterated Thursday that the economy is “in a very good place,” but that the central bank has room to lower interest rates to keep the expansion on track. As dovish as that may sound, the comments didn’t offer much comfort to bond traders – they had other things on their minds.

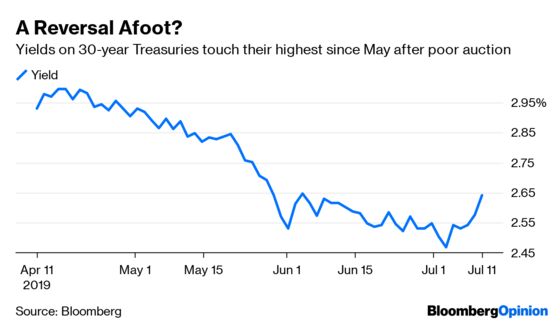

For the second time this week, the U.S. Treasury held a bond auction that met with less than stellar demand, triggering losses across all maturities and pushing yields on longer-dated debt to their highest since May. Investors submitted bids for just 2.13 times the $16 billion of 30-year bonds offered. To put that in perspective, consider than in the almost 50 auctions of that maturity since mid-2015, the bid-to-cover ratio has been lower just three times. Not only that, the yield of 2.644% was higher than the 2.618% the securities were trading at just before the auction, generating the highest so-called tail since early 2016 and confirming the weak demand. “Friendless long bonds abandoned at sale,” is how FTN Financial interest-rate strategist Jim Vogel titled his report on the auction. While short-term debt is highly influenced by the direction of monetary policy, longer-term securities are more sensitive to things like inflation and perceived creditworthiness. And in that regard, bond investors have plenty to worry about. The government said just a few hours before the auction that the core consumer price index, which excludes food and energy, rose 0.3% from the prior month, the most since January 2018 and enough to raise doubts about the notion that inflation really is dead.

There other good reasons for bond investors to be cautious on longer-term U.S. debt. The Trump administration is openly talking about how it would desire a weaker greenback, which for many is a sign that the U.S. is abandoning its long-held strong-dollar policy. Put another way, who wants to hold long-term, dollar denominated assets while the U.S. government is doing everything it can short of actually intervening to weaken the dollar? As for the creditworthiness of the U.S., the Treasury Department said after the auction that the budget deficit widened by 23% to $747.1 billion in the first nine months of the fiscal year. Prospects for faster inflation, a falling dollar and more borrowing isn’t a recipe for a bull market in bonds.

STOCKS SURPRISE

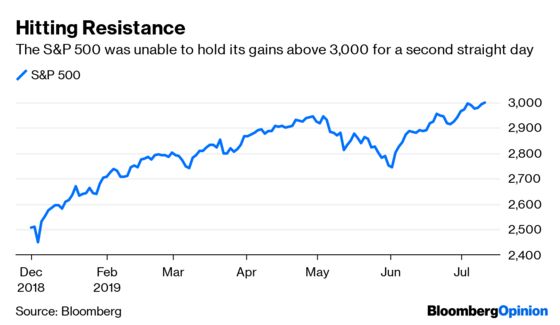

Although the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed on Thursday above the 27,000 market for the first time, the more important S&P 500 Index rose above 3,000 for the second straight day only to fall back to just below that level to 2,999.91 by the end of trading. Given how important falling bond yields have been to the rally in stocks, it was impressive that equities didn’t fall out of bed along with the Treasury market. The reason may be found in the CPI report. The thinking here is that if inflation really is accelerating, then perhaps companies will finally be able to pass on price increases to their customers, reversing the trend toward narrower profit margins. “The June CPI report vindicates Chair Powell's earlier assessment that some of the recent slowdown in inflation was at least partially due to transitory factors,” Bloomberg Economics’s Yelena Shulyatyeva wrote in a report. Profit margins for S&P 500 companies have narrowed from 12.6% in last year’s third quarter to a likely 11.7% for the second quarter, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. “The forecast for double-digit net income growth by this time next year won't happen without margin gains,” the strategists with Bloomberg Intelligence wrote in a report Wednesday.

DOLLAR POLICY

Trump will get a weaker dollar, just probably not as weak or as soon as he wants. Although the U.S. Dollar Index has fallen to 97.064 on Wednesday from this year’s high of 98.203 in April, the median estimate of currency strategists surveyed by Bloomberg is for it to drop to 95 by year-end. That would only put the gauge at its lowest since October – not enough to do a lot for exporters, considering it was below 90 in early 2018 and around 80 in mid-2014. As such, the new favorite parlor game in the currency market is speculating on whether the U.S. might intervene to weaken the dollar, and if so, how it might accomplish that feat. It wouldn’t be easy. The U.S. would likely need the help of other nations, because the $5 trillion-per-day market is too deep for unilateral U.S. action to have any impact. And given how quickly the global economy is weakening, the U.S. would be hard-pressed to get any other nation to help it push the dollar lower, as that would have the effect of strengthening their own currencies. The most effective move might be the simplest. All the U.S. would have to do is officially abandon the strong-dollar policy introduced in 1995, according to the strategists at Bank of America Merrill Lynch. Such a shift could be a “game-changer,” the strategists wrote in report Thursday. But that brings up another set of problems, such as international investors potentially shunning dollar-based assets and causing U.S. borrowing costs to rise. Was the 30-year bond auction Thursday a glimpse of the future?

EMERGING MARKETS PREFER EUROS

The euro zone economy is worse off than the U.S. and the Bloomberg Euro Index is down about 5.50% since April 2018. And yet, emerging-market borrowers are issuing debt in euros at a record pace to meet demand, another sign that perhaps investors might be shunning the dollar. Emerging-market sovereigns have collected 33.5 billion euros ($37.7 billion) from new bonds his year, more than the amount raised in any full year previously, according to Bloomberg News’s Srinivasan Sivabalan. Togo, the tiny West African nation with a gross domestic product that’s less than the annual revenue of 70% of the companies in the S&P 500 Index, was the latest to borrow in euros, joining countries including Saudi Arabia and Turkey. The dollar’s share of global currency reserves dropped to 61.8% as of the end of March from 65.4% at the start of the Trump administration, according to the International Monetary Fund. The euro’s share has risen to 20.2% from 19.1% in the same period. To be sure, emerging-market borrowers tapping the euro market to raise funds isn’t solely a currency play; it’s also about interest rates. The average yield on a Bloomberg Barclays gauge for emerging-market euro bonds is 1.67%, more than 3 percentage points lower than the rate on a comparable index of dollar bonds, according to Sivabalan.

RUSSIA ROILS THE WHEAT MARKET

The cost of bread may soon rise, and it’s all Russia’s fault. Wheat futures climbed the most in a month on Thursday after the U.S. Department of Agriculture delivered a bigger-than-expected cut to its production estimate for Russia, the top exporter, according to Bloomberg News. Scorching temperatures are signaling fewer exports out of Russia and Ukraine, which should also result in more U.S. shipments, the USDA said in its monthly World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates report. The agency lowered its forecast for Russian production to 74.2 million metric tons for the 2019-20 season, down from a previous outlook of 78 million. As a result, Russian wheat exports are expected to fall for a second year, the first back-to-back drop in at least three decades, Bloomberg News’s Megan Durisin reports. Fewer shipments from Russia is a boon for rivals. The USDA boosted estimates for sales from the U.S. and European Union.

TEA LEAVES

After the mild surprise in the consumer price index on Thursday, the producer price index set be released on Friday suddenly becomes much more interesting. It’s not that the report will have any bearing on whether the Fed will or won’t raise rates; but it could have implications for equities. For one, profit margins won’t benefit even if companies can sell their goods and services for higher prices if the prices they are paying for materials to make those goods and services are also rising by the same or greater amount, broadly speaking. The median estimate of economists surveyed by Bloomberg is for the government to say that that producer prices were flat in June from a month earlier, but increased 0.2% when stripping out volatile food and energy costs. They are expected to increase 1.6% from a year earlier, or 2.1% excluding food and energy. Both readings would be 0.2% below the readings for May.

DON’T MISS

Fed Satisfies Fewer and Fewer These Days: Mohamed A. El-Erian

Europe's Leaders Must Learn From the Greek Tragedy: Mervyn King

Here Come the Earnings Disappointments: Brooke Sutherland

Lagarde's ECB Is Running Out of Economists: Ferdinando Giugliano

A $15 National Minimum Wage Isn’t So Scary After All: Noah Smith

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is an editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.