A Tale of Two Resource Giants Contains a Warning for Brazil

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- How the mighty have fallen. Petroleo Brasileiro SA, or Petrobras, was once the darling of Brazil’s stocks exchange, briefly worth as much as a fifth of the entire market early in 2009. It’s now languishing. Shares have fallen 16% this year despite a general rally for oil producers, and worse lies ahead.

Joaquim Silva e Luna, a former general and defense minister under President Jair Bolsonaro, has been named to the board and is expected to be appointed as chief executive officer, people with knowledge of the internal vote told Peter Millard and Vinicius Andrade of Bloomberg News on Monday. That will put the seal on a two-month fight to place a Bolsonaro loyalist in Petrobras’s top job, after a clash over fuel-pricing policy forced out his predecessor, Roberto Castello Branco, and caused the stock to lose about a quarter of its value in three days.

The contrast with Brazil’s other resource superpower is telling. Shares in iron ore giant Vale SA hit a record high last week after it announced plans to buy back about $4.9 billion of its own shares. With a market capitalization of about 96 billion reais ($17 billion), it’s now closing in on twice the 54 billion reais valuation given to Petrobras. Analysts expect Vale, for most of its existence the clear junior in terms of revenue, to earn three dollars this year for every dollar of net income that goes to Petrobras.

In a market where both crude and iron ore are buoyed by a reviving global economy, this view is the clearest indicator that the Petrobras model of mixing up state and corporate business — and, in the Bolsonaro era, throwing in the military for good measure — is a shortcut to failure.

On paper, the two companies have a lot in common. Both dominate one of Brazil’s key exports, and both are former state-owned companies with substantial listings on exchanges in Sao Paulo and New York. That’s where things start to diverge, though. While the government’s continuing 50.5% stake in Petrobras’s ordinary shares gives Brasilia complete power over decision-making, its long-standing control in Vale, guaranteed by a complex web of state pension funds and holding companies, has been whittled down almost to nothing. Apart from a state “golden share” guaranteeing Vale won’t switch into another line of business, the government these days has lost almost all influence in the boardroom.

That’s good both for Vale, and the state itself. The ties between Petrobras and powerful politicians prompted the mammoth Carwash anti-corruption investigation, which helped end the careers of Bolsonaro’s predecessors Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, Dilma Rousseff — herself chairman of the company between 2003 and 2010 — and Michel Temer, who took office after Rousseff’s impeachment.

Presented with a business taking in hundreds of billions of reais each year and controlled by the government, the temptation to embezzle money for advantage and influence proved irresistible. Vale has hardly had a spotless record in recent decades — it agreed in February to pay $7 billion in compensation after a 2019 tailings dam disaster killed 270 people, and former Chief Executive Fabio Schvartsman is facing homicide charges over the same incident. Still, in an era when it seems every major Brazilian company has been swept up in the wake of Carwash, Vale has never been treated as a secret cash machine for the political class.

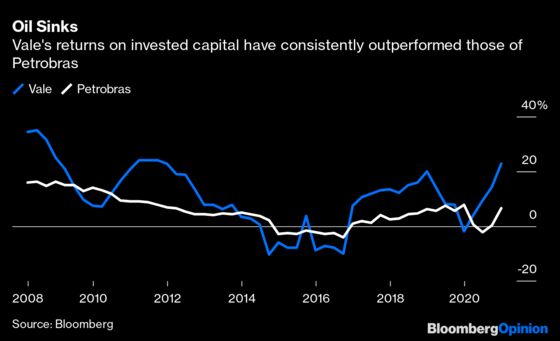

Keeping its distance from the politics has also meant that Vale has generally been pretty well-run. Its returns on invested capital consistently outpace those of its oily cousin, and track pretty closely with those of private rivals like BHP Group and Rio Tinto Group. Petrobras last posted returns sufficient to cover its capital costs in 2008. Vale has achieved that yardstick in nine out of 15 quarters since the 2017 restructuring that removed the main vestiges of government influence.

There’s a broader lesson in that. The most alarming nexus for conflicts of interest in Brazil these days isn’t where the political and corporate classes meet, but where politicians brush up against the military.

Bolsonaro has long spoken fondly of Brazil’s two-decade military dictatorship, under which he served as a junior officer. In recent weeks, the three heads of the armed forces and a host of senior officials have quit or been sacked, amid a push from the president for the military to take sides in his Trumpist campaign against coronavirus restrictions imposed by state governors.

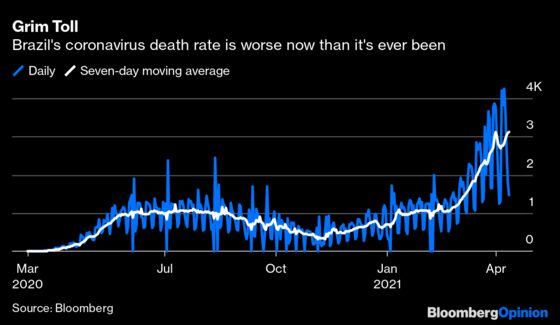

With Lula now potentially facing off against him in a presidential election due next year, and Brazil in the grip of the most deadly phase yet of its Covid-19 pandemic, erasing the boundaries between political and military power now may look as fatally tempting to Bolsonaro as blurring the lines between politics and business seemed to his predecessors. Citizens, as well as investors, must hope Brazil avoids that fate.

Lula’s conviction was dismissed last month but he's likely to face a re-trial over the same events.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.