Inflation Is Just a Monster Under the Bed for Investors

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Economic recoveries are supposed to be a time of celebration for investors, and the recovery from Covid-19 now underway should be no different. The economy is growing again; business activity is picking up; deflation is a distant threat; cheap money is goosing the recovery; and stocks are surging on hopes of higher profits.

And yet, rather than cheer their good fortune, many investors appear to be tormented by the recovery’s potential pitfalls. One of the most feared scenarios is that inflation will spike, pushing interest rates higher and tanking the stock market. While it can’t be ruled out of hand, there’s little indication that a worrisome jump in inflation is coming.

Sure, in theory, the table is set for higher prices. Supply lines are strained. Congress and the Federal Reserve have spent or committed about $9 trillion to fight the pandemic, the largest stimulus and relief effort in history. And the personal saving rate has never been higher, so those who have prospered during this pandemic have money to spend. If inflation picks up, higher interest rates and lower stock prices could follow. Inflation and interest rates moved in close step during the 1970s, the last time the U.S. experienced a surge in prices. Also, the U.S. stock market is priced for perfection, with a forward price-to-earnings ratio only slightly below the peak of the dot-com bubble, so it’s vulnerable to bad news.

That may explain the nervous gasps in response to recent market moves. The 10-year breakeven rate, a widely cited gauge of expected inflation that tracks the difference in yield between nominal and inflation-protected Treasuries, rose modestly above the Federal Reserve’s inflation target of 2% recently, up from about 0.5% last March. Seemingly on cue, the yield on 10-year Treasuries climbed to 1.6% from 1% roughly a month ago. At the same time, once unshakable tech-related stocks have taken a small dive. The venerable NYSE Fang+ Index is down about 9%, and the Nasdaq 100 Index is off roughly 4% since mid-February.

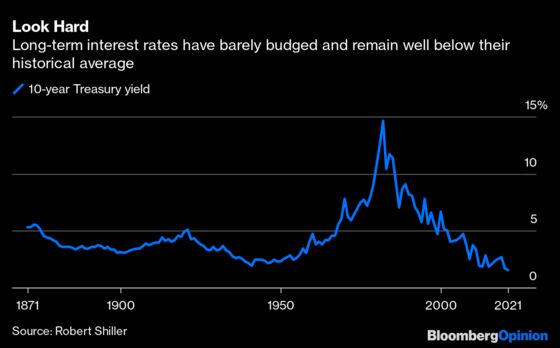

Pull back the lens, though, and those moves look benign. Consider, for example, that annual inflation has averaged 2.2% since 1871, according to numbers compiled by Yale professor Robert Shiller. In that light, the breakeven rate appears merely to have inched closer to the long-term inflation rate, which seems appropriate given that the economy is returning to normal, too. Meanwhile, the yield on 10-year Treasuries has averaged 4.5% over the last 150 years, so even after its recent move higher, the 10-year yield is still shockingly low.

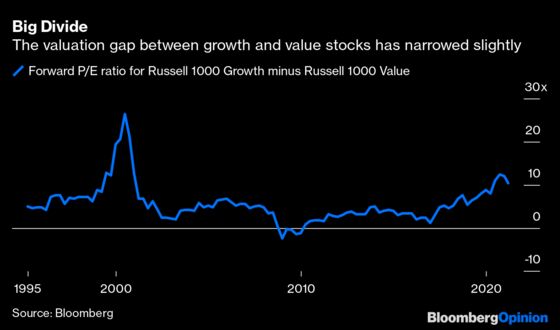

There’s not much to see in the stock market, either. While big tech shares and growth stocks more generally have stumbled, the broader market hasn’t moved. The Russell 1000 Index is little changed from its high on Feb. 12. And some stocks are surging — the Russell 1000 Value Index is up 5% over the same time. That divergence between growth and value is more likely driven by valuations than modestly higher interest rates. There’s been no correlation in the past between the level of interest rates and the valuation gap between growth and value stocks. But notably, the gap was among the highest ever recorded last year, so it was due to deflate. In any event, it hasn’t narrowed much.

In other words, despite all the fuss about inflation expectations, interest rates and stocks, little has happened so far. That’s important for investors to keep in mind because there’s no shortage of hucksters eager to sell them all sorts of expensive and unnecessary portfolio “insurance” against the coming scourge of inflation and resulting market turmoil. Amid the flurry of slick sales talk, it’s easy to forget that a simple, balanced, low-cost portfolio of stocks and bonds has served investors well in the past and has more than kept pace with inflation over time, even during the 1970s. To that end, investors who have binged on U.S. growth stocks and long-term bonds in recent years can strike a better balance by shortening the maturity of their bonds and expanding their stock portfolio, both within the U.S. and abroad.

If the 1970s is any guide, investors will have plenty of warning that inflation is moving in a worrisome direction. Inflation began to tick up long before reaching its twin peaks of 12.2% and 14.6% in 1974 and 1980, respectively. It first edged higher in 1966, doubling to 3.8% in October from 1.9% in January. After declining for several months, it gradually resumed its climb to 6.4% in early 1970. Those warning shots didn’t signal that higher inflation was sure to follow, obviously, but they alerted investors that inflationary forces were afoot. There is nothing remotely comparable going on today. The inflation rate was 1.7% in February, up from a dangerously low 0.2% last May but still well below the Fed’s target.

Another difference between the years leading up to the 1970s and today is that the Fed — indeed everyone — is on guard for a replay of that fearsome episode. Last time, the Fed didn’t intervene until the late 1970s, more than a decade after inflation reared its head. It’s not likely to fall behind the policy curve again, to paraphrase Mary Daly, president of the San Francisco Fed.

Inflation may yet become a problem, but that’s far from obvious. Keep an eye on the monthly numbers. If annual inflation rises meaningfully higher than its long-term average for several months, it may be a sign that inflationary pressures are building. Until then, the fear of inflation is a greater threat to investors than inflation itself.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.