Americans Need to Learn to Live More Like Europeans

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It's become the conventional wisdom that the U.S. economy is built on Americans' endless appetite to buy lots and lots of stuff. Household consumption makes up about 67% of GDP. When the economy falters, we're told spending is our patriotic duty. But suddenly, Americans can’t spend like they used to. Store shelves are emptying, and it can take months to find a car, refrigerator or sofa. If this continues, we may need to learn to do without — and, horrors, live more like the Europeans. That actually might not be a bad thing, because the U.S. economy could be healthier if it were less reliant on consumption.

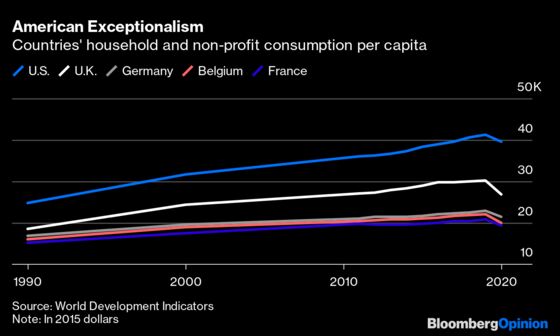

After all, Americans haven't always acted like this. We've entered an age of overabundance. We consume much more than we used to and more than other countries. Consumption per capita grew about 65% from 1990 to 2015, compared with about 35% growth in Europe. Household consumption makes up only about 50% of GDP in Germany.

And these numbers reflect big changes in Americans' lifestyle. The average U.S. home was 1,700 square feet in 1980, by 2015 it was 2,000 square feet, even though the number of people in the average household shrank. In 1980, 15% of households didn’t have a TV, now only about 3% don’t. In 2015, 40% of American households had three or more TVs, including 30% of households earning less than $40,000 a year! In 1980, only 13% of households had 2 or more refrigerators, in 2015 30% did — including many low-earning households. Clothing purchases have increased five-fold since 1980 and the average garment will only be worn seven times before it's disposed of.

Our spending habits slowed some during the pandemic but, despite all the shortages, they've come roaring back.

There are many reasons we’ve become a nation of shopaholics. We’ve become a richer country which means we spend more. Many goods have become cheaper and more accessible. That's partly because of technology that makes production more efficient. For shoppers, the Internet makes it easier to find more goods for the best prices without even leaving your home. The other big factor is we get more stuff from abroad, imports of goods and services as a share of GDP has nearly doubled since the 1980s. Lots of trade has been with countries like China and Mexico who have lower labor costs. Even American-made goods use parts that come from abroad. We experienced the vulnerabilities of a global supply chain in the last few years, but when it does work (most of the time) it means the U.S. can fully exploit the comparative advantages of trade and provide goods more efficiently, faster and for less money.

The pandemic revealed vulnerabilities of this hyper-efficient global market. Ports are backed up causing shortages — for the first time in many Americans’ lives. The odds are that eventually the port issues will be resolved (we hope). But there are reasons to believe the age of over-abundance is over. Even before the pandemic the U.S. government offered more subsidies and imposed more tariffs to encourage companies to produce more goods domestically, and the Biden administration wants to expand the effort to promote resilency. That may mean more goods are made in America, but over the long run less trade tends to mean less variety of goods at higher prices.

Meanwhile, the U.S. economic relationship with China becomes more uncertain each day. If it deteriorates further, that also tilts the U.S. toward less trade and fewer cheap goods. The future of trade is a big unknown, but if we turn inward, Americans won't be able to sustain the same levels of consumption.

Finally, if we are truly serious about protecting the planet, being a good global citizen will take more than driving an electric car or installing solar panels. It means consuming less so that we throw less away. Maybe that means getting by with only one refrigerator or avoiding fast, disposable fashion.

Americans tend to overspend or buy cheap substitutes rather than save up for longer-lasting, better-quality goods. That's a function of the accessibility of cheap goods, of having more space to store our purchases, and also of a culture where buying stuff feeds the empty part of our souls. European souls are not necessarily more fulfilled, they just find other, more eco-friendly ways to shut out the darkness — like going on a long bike ride.

In short, with higher prices, a more eco-conscious population and less trade bringing fewer cheap products, Americans may have to get used to consuming like Europeans. We will certainly not be deprived, but we will trim back our excesses, perhaps be more thoughtful about what we buy and purchase fewer, higher-quality goods.

What would that mean for the U.S. economy? European levels of consumption coexist with lower levels of growth. It feels like our voracious consumption is what fuels the economy. But that needn’t be the case. Long-term, sustainable growth doesn't come from going deep into debt to buy stuff we don't really need. It comes from technology and innovation, where we come up with new products and better ways of doing things. An economy based on consumption is not sustainable.

Tufts University business professor Amar Bhide argues that what’s great and unique about American consumption is openness to new products and new ideas. Historically, America was a nation of early adopters. This, not just volume, has been what has propelled American growth because it creates a vigorous marketplace where new products can find a market, experiment and improve. Buying smart, while maintaining an openness to new things, can be the foundation of a more sustainable and growing economy.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Allison Schrager is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. She is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and author of "An Economist Walks Into a Brothel: And Other Unexpected Places to Understand Risk."

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.