(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Some U.S. exports to Europe are more welcome than others. The next ocean-hopping trend could be large day-one gains for newly listed stocks — so-called IPO pops. If European initial public offerings made investors more money more often, they’d certainly become more popular. The risk is they end up being an undeserved free lunch for a favored few.

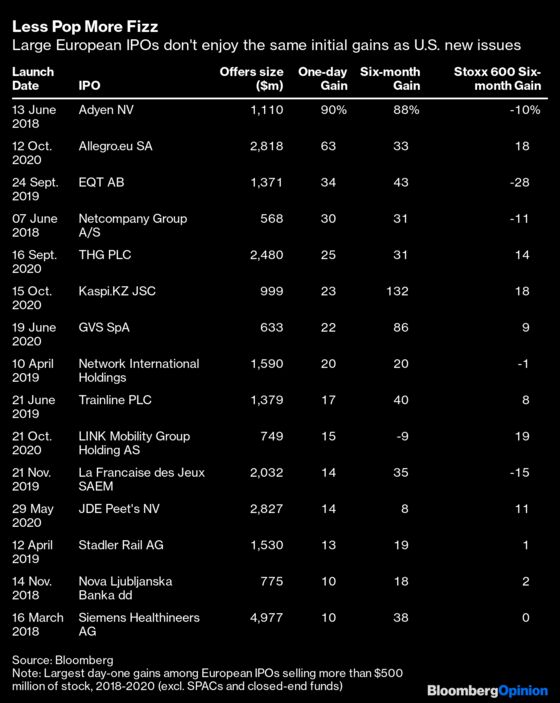

DNA sequencer Oxford Nanopore Technologies Plc closed up 44% on its first day of trading last week, ending the session valued at 4.9 billion pounds ($6.7 billion.) That’s a rarity. From 2018 to 2020, only two new European stock offerings raising more than $500 million climbed as high on debut, while the median average day-one gain was 4%, based on calculations using Bloomberg data .

With hindsight, Nanopore’s selling shareholders could have offloaded their shares at a higher price and still the deal would have been regarded as a success.

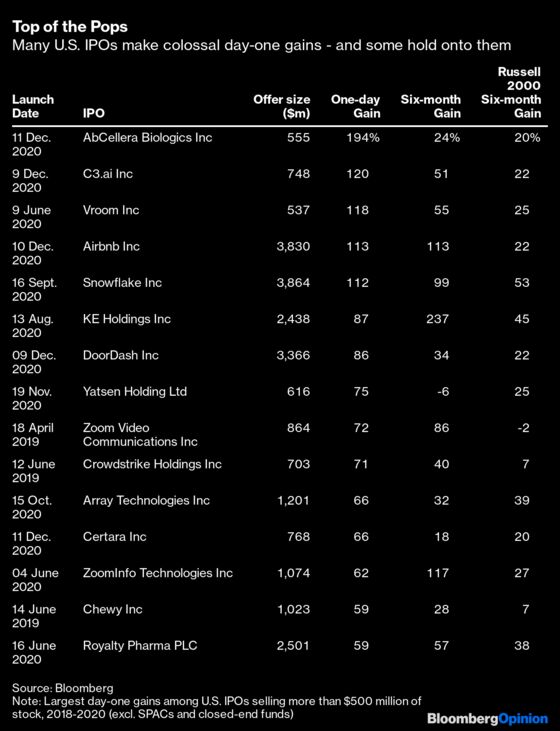

It’s a different story in the U.S. With the same sample criteria, 20 U.S. IPOs popped as much as Nanopore — about one-fifth of the total. The median average day-one gain was 20%. This was no flash in the pan. Judged on six-month performance, the average gain was 21%. Expand the sample to include smaller new stock issues and the performance numbers are even higher.

Convention and regulation explain the transatlantic divide. U.S. IPOs are akin to a marketing event. While selling IPO stock cheaply disadvantages existing owners at the start, the resulting pop creates an aura of success. Perhaps that makes it easier to sell the remaining shares in the future. Better to take a big discount on a small initial stock sale than risk a flop that renders the IPO damaged goods, or so the argument goes.

The well-known concern with the U.S. IPO market is that it essentially sees sellers give away value to buyers. That’s fueled the popularity of so-called direct listings, in which shares just start trading without a big block changing hands at a pre-determined price as in an IPO.

These contrasting approaches have a lot to do with how much — or rather how little — of the company must be sold in an IPO. Europe’s main listing venues typically demand a quoted company has at least 25% of its shares freely tradeable. If the IPO firm’s ownership structure is concentrated, perhaps because it belongs entirely to a single buyout fund, this minimum “free float” will have to be generated entirely by the shares sold in the IPO.

The more a vendor has to sell at the outset, as opposed to later on, the less willing it will be to take a cheap IPO price. In the U.S., free-float requirements aren’t percentage-based.

Nanopore was unusual in this respect. It had a fragmented ownership structure including several public-market shareholders before it went public. That meant it already satisfied London’s free-float requirements and was able to sell only 17% of itself in its IPO. Structurally it may have had more in common with a U.S. deal than first appears. It was a similar story with cybersecurity company Darktrace Plc, which set out to sell only 10% of itself in its small April IPO and popped 32%.

The U.K. regulator has been seeking views on cutting free-float requirements to 10%. In itself, that’s welcome as it will broaden access to the London market for firms looking to go public. If the owners of IPO companies then chose to sell less stock but more cheaply, U.K. new issues could well deliver Nanopore-style gains more often. In turn, that could attract more investors.

Fine, if those taking businesses public know what they’re doing. Still, it would be a shame if this became the new playbook. Investing is meant to be about risk, and that’s especially the case for an untested stock. Regular mega-discounts on IPOs would just turn the London market into a one-way bet for those few investors lucky, well-connected or pushy enough to get a cut of the deal.

The sample excludes closed-end funds and cash shells.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Hughes is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals. He previously worked for Reuters Breakingviews, as well as the Financial Times and the Independent newspaper.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.