(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Now that it’s clear populists, nationalists and assorted euroskeptics will hold little real power in the incoming European parliament, it’s important to analyze their specific gains and losses in last week’s election to see where the European project of continued trans-national integration, including monetary union, has problems and where it doesn’t.

To avoid having to argue terminology in every specific case, I’ve made up an inoffensive acronym for the populist, illiberal, nationalist and euroskeptic parties: PINE. Some of these political forces are members of one of three nationalist, populist and euroskeptical groups in the outgoing European Parliament – European Conservatives and Reformers, Europe of Nations and Freedom and Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy – and others aren’t. But they’re all from the same PINE forest because they challenge the EU establishment and its course of further integration at the expense of national sovereignty. The following analysis excludes extreme left forces that may also be against the European project because of their negligible influence and the small chance that they’ll make common cause with the stronger far-right flank.

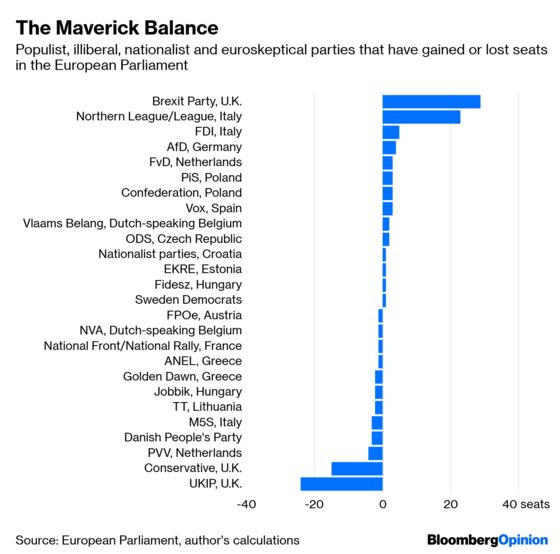

According to the new parliament’s seat distribution based on preliminary results, 15 PINE parties throughout the European Union made gains in the election and 12 lost seats. In total, they gained just 25 seats – 3.3% of the total of 751. Without Italy, they would have come out even with the 2014 result. In a small number of countries there has been no change in PINE support.

The rise of Italian nationalism and what one could call an anti-establishment revolution there make the country the EU’s biggest trouble spot for the next legislative period. It’s unclear what the bloc can do about it except wait for Italians to become disappointed in Matteo Salvini’s League (and the national conservative Brothers of Italy, or FDI, party) – something that might come with painful economic side-effects.

The U.K. is the other obvious problem, but perhaps a receding one – either because Brexit will eventually happen or because it won’t. Last week’s election delivered a net loss of seats to British PINE parties. The success of Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party was as spectacular as the downfall of his former project, the U.K. Independence Party, and the ruling Conservatives faced a catastrophic loss that doesn’t augur well for them in the next general election. All this is for the British voters to sort out, though: The EU can hardly help at this point and it’s wise for it to wait out the crisis.

Other than the two obvious hot spots, eastern Europe remains somewhat problematic for the “ever closer union” project because of the strength of Hungary’s Fidesz and Poland’s Law and Justice (PiS). These aren’t exactly euroskeptical parties, but they are focused on not giving up any more national sovereignty, and they’re resolutely illiberal. The parties work to defang the independent media and build up propaganda machines that make them immune to scandals (PiS survived a whole strong of them in the run-up to the European election) and they tighten the political control of the courts.

The longer they remain in power, the less likely that elections in these countries will be free and fair. In Hungary, it may be too late to do anything about it because the disunited opposition there cannot mount a convincing challenge to Fidesz. In Poland, the opposition has shown a higher propensity for compromise and alliance-building, and it may live to fight another day.

The nationalist populists and national conservatives also gained considerably in the Czech Republic. Although they don’t govern there, polls consistently show that the Czechs doubt the usefulness for their country of being in the EU. It’s an underappreciated challenge for the European elite: Although small, the Czech Republic, with a higher living standard than other post-Communist nations, is a key country to keep involved in building a stronger Europe.

Other than this, EU leaders have little to fear. Marine Le Pen has made no progress in France despite the Yellow Vest protests, which could have benefited her as an anti-establishment leader. In Spain, the gains of the nationalist Vox party have been offset by the success of Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez’s socialists. And in the German-speaking countries, a massive scandal involving Austria’s former vice-chancellor Heinz-Christian Strache has driven home the danger of courting the nationalists. It hurt Strache’s party, the FPOe, which underperformed in the European election.

One of the leaders of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party, Alexander Gauland, has speculated that Strache’s downfall has also depressed AfD’s support. Though the German nationalists gained seats compared with the 2014 election, their share of the vote is down compared with Germany’s last national election; but perhaps the Strache affair has less to do with that than the receding importance of immigration as a hot political issue in most of Germany except its easternmost part.

EU politics have always been a dense forest of different parties and interests, but after last week’s election, it’s predominantly leafy and green. The PINEs occupy less than a quarter of the total area, and that’s healthy for the ecosystem. Pessimists should take a walk in these woods, it’s guaranteed to get their spirits up.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Therese Raphael at traphael4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.