(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Some 18 months on from staring into the abyss, Scott Sheffield of Pioneer Natural Resources Co. is gazing into the clouds.

In April 2020 the shale CEO was calling, in vain, for the Texas Railroad Commission to impose production quotas to deal with the oil crash. Today, with oil around $80 rather than $20, Sheffield says instead the industry can self-police with unusual rigor — no matter how high oil goes:

“Everybody’s going to be disciplined, regardless whether it’s $75 Brent, $80 Brent, or $100 Brent,” Sheffield said. “All the shareholders that I’ve talked to said that if anybody goes back to growth, they will punish those companies.” (as quoted in the Financial Times.)

Whether his prediction of discipline holds or not, Sheffield’s comments capture an important shift in oil that predates Covid-19 but was undoubtedly accelerated by it: The more unpopular oil gets, the more expensive it becomes.

That doesn’t apply to demand, which is being given new impetus by higher natural gas prices. But on the supply side, things have changed. A few weeks ago, Chevron Corp. CEO Mike Wirth told Bloomberg News that, when it comes to growing production:

There are two signals I’m looking for and I’m only seeing one of them … We could afford to invest more. The equity market is not sending a signal that says they think we ought to be doing that.

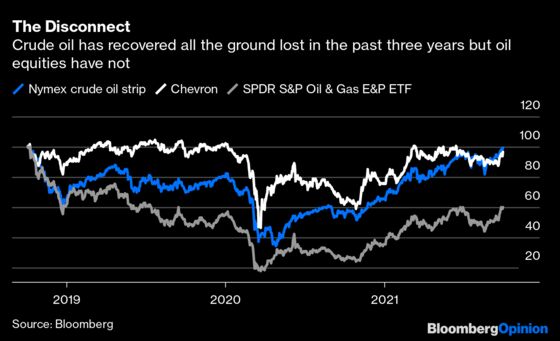

Oil is back to where it was three years ago, when the U.S. oil rig count was about double today’s level. Chevron’s stock has also recovered to October 2018 levels, yet Wirth still feels constrained (Pioneer has made up all that ground, too). As for the broader sector, though, it is definitely in a different place.

Back before the 2014 crash — the last time oil executives felt able to say “$100” without fear of being struck by lightning — high oil prices were justified on the basis of cost inflation. Too many dollars chasing too few rigs and roughnecks, essentially. Today, there’s a lot of unemployed roughnecks around. The problem is too few dollars chasing them. The industry’s cost of capital has gone way up.

The reasons for this fall mainly into two buckets: lingering investor distrust due to the excesses and losses of the prior boom and concerns about oil’s future in general. The latter incorporates efforts by the Biden administration to slow drilling, although that looks more like an issue for the future. Certainly, private E&P operators don’t appear to be too constrained today, if their rig counts are any guide.

The broader ESG push is having an impact, though. Wirth’s comments came on the heels of a new set of low-carbon targets for his company. Meanwhile, a green specter hung over Royal Dutch Shell Plc’s recent $9.5 billion disposal of its Permian-basin assets to ConocoPhillips. What caught my eye was Shell selling at an eye-watering implied free cash flow yield, on 2022 estimates, of 20% and promising to pay out the proceeds. Meanwhile, Conoco pitched the deal to its own shareholders at a yield of 10% (based on projections for the decade at $50 oil). Clearly, the ESG burden falls unevenly. Yet both companies felt compelled to reiterate discipline, backed by double-digit capital costs.

With OPEC+ meeting Monday, the timing of Sheffield’s comments was hardly accidental. He added the current oil market is “really under OPEC control.” Yet OPEC+ appears unwilling to respond with more supply, with oil prices jumping again Monday morning as a result. Its secretary general chided “activist investors” last week for deterring spending on new production. This rather elides the structural weaknesses of many OPEC+ members, including deterrents to more private investment.

The bigger point, though, is that despite high energy prices and talk of crisis, both OPEC+ and the U.S. shale sector aren’t rushing to add more supply. It’s possible to interpret this as an effort to derail green agendas, but that feels unnecessarily conspiratorial. Rather, the cost of oil has increased, but for reasons above the ground rather than below.

The flood of dollars into shale for much of the past decade suppressed the price of barrels, just as cheap money suppressed the price of ride-sharing or flexible office space. Fracking is more efficient than it was 10 years ago, but investors now demand more, a lot more. Similarly, the costs of maintaining and repositioning petrostate economies mean the famed low-cost production of OPEC+ members isn’t quite as low cost as advertised.

This may all yet change. Sheffield’s prediction of discipline holding even if oil hit $100 looks especially dubious. Moreover, at that point, it is the damage to economic recovery, and thereby oil demand, that may decide things rather than the considerations of suppliers.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.