If This Is Peak Inflation, What’s the Path Back to 2%?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- After the consumer price index data for October shocked markets, economists, the Biden administration and Federal Reserve officials, there was no chance the Labor Department’s release of November’s CPI on Friday would catch anyone unaware. Its proximity to the central bank’s coming decision only added to the suspense on what was dubbed “the new jobs day.”

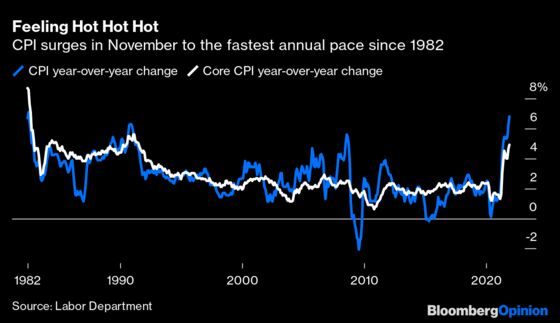

The top-line takeaway — that headline U.S. CPI rose at the fastest annual pace since 1982 — was never really in doubt. Instead, the more pressing question was whether inflation would keep up its blistering month-over-month increases, which, in Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s estimation, were supposed to have subsided. Instead, sharply higher prices across the board came roaring back in October, leading him to acknowledge in a conspicuous pivot that “it’s probably a good time to retire” the word “transitory.”

The swift acceleration in consumer prices continued last month. Headline CPI jumped 6.8% in November from a year earlier and 0.8% from October. Those figures were both about in line with estimates in a Bloomberg survey of economists. Core CPI, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, climbed 4.9% from 12 months ago, matching expectations, and 0.5% from October.

The initial reaction across markets — U.S. stock futures higher, Treasury yields lower — suggested some relief that inflation didn’t smash through estimates again. If the data came in as hot as before, CPI would have exceeded 7% and the core measure would have topped 5%. Still, matching expectations for the fastest consumer price growth in almost 40 years isn’t exactly a victory for policy makers or American workers. Friday’s data also provided a reminder that real average hourly earnings fell 1.9% from 12 months earlier.

Most economists agree that U.S. inflation is likely at or near its peak, with Bloomberg Economics expecting headline CPI to hover around 7% for several months, while the core measure may top out February or March around 5.5% to 6%. Even President Joe Biden on Thursday made a point to emphasize that “in the weeks since the data for tomorrow’s inflation report was collected, energy prices have dropped.” The pressing question, then, is how will it get back to the roughly 2% level that the Fed targets for price stability?

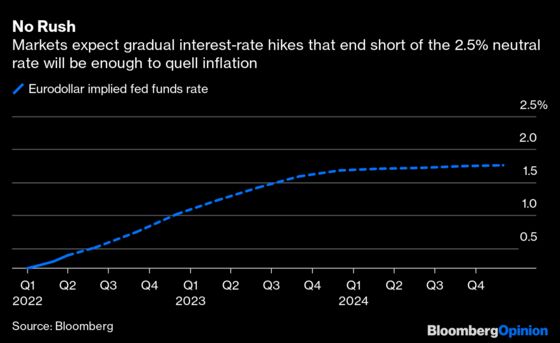

The most recent Bloomberg survey of economists shows an expectation for headline CPI to retreat to 3.7% in 2022 and then 2.3% in 2023, while the personal consumption expenditures index will slip to 3.2% and 2.2% in the next two years. In that same survey, respondents on average didn’t see the Fed raising interest rates until December 2022, and then three more times throughout 2023, which is roughly consistent with the path that central bankers sketched out in September.

That reflects remarkable confidence in inflation auto-correcting without much immediate Fed action. But the central bank will update its “dot plot” next week — and some are expecting big changes. Earlier this week, former New York Fed President Bill Dudley wrote a Bloomberg Opinion column detailing why he expects policy makers will forecast a median of three interest-rate increases next year, four more in 2023, and then a few more in 2024 to bring the fed funds rate to its long-run neutral level of 2.5%. Typically, once the central bank starts tightening, it keeps going until the fed funds rate is above the level of inflation.

I’m not convinced that Fed officials will rush to pencil in three interest-rate increases in 2022, up from less than one in its September forecast, especially after abruptly speeding up its tapering pace. More likely, the median will show two rate increases in 2022, leaving policy makers flexibility to move as soon as March if necessary, at which point they could lift their outlook for the rest of the year.

The risk to this gradual approach is that it could do little to nothing to alter the trajectory of inflation. It’s true that as Biden mentioned, there’s been some easing in energy costs, which should help suppress headline CPI. But just as that starts to fade, housing is starting to cause headaches. Rent and what’s known as “owners’ equivalent rent” both increased 0.4% in November from a month earlier, which comes out to an almost 5% annual rate.

According to David Wilcox of Bloomberg Economics, a former director of the Fed’s division of research and statistics, it might only get worse. The main parts of CPI that measure housing costs, which represent almost one-third of the overall index value, could be in the 6% to 7% range by the middle of next year, the highest in three decades. “Short of tanking the economy, there is little policy makers could do to prevent today’s increases in asking rents from feeding into headline inflation,” Wilcox wrote this week. “Their job will be to block a one-time increase in rents from stoking an ongoing process. That could necessitate larger rate increases.”

The Fed’s stated policy is to raise interest rates when inflation is at 2% and also “on track to moderately exceed 2% for some time.” Even if CPI is at or near its peak around 7%, that’s a long way from the stated level that’s consistent with price stability. Does the Fed get there with more aggressive action in the first half of 2022, when its three-part test to leave the zero lower bound will clearly have been met? Or, as it has for most of this year, will Powell and his colleagues talk a good game about how price growth will eventually slow without actually doing much of anything to tighten monetary policy?

Both paths are fraught with peril. The best thing the Fed could do would be to remain nimble. The quick pivot on its tapering pace in recent weeks was a good start, but lining up rate hikes will be a much tougher task.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.