It’s the Dagger You Don’t See That Kills a Bull Market

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- When you’ve been in this business as long as I have — four decades and counting — there are inevitably a few articles that you look back on with a grimace. For me, the cover story I wrote for Fortune magazine in October 1999 ranks right up there.

If Netscape’s public offering in August 1995 marked the beginning of the dot-com bubble, that October four years later marked the beginning of the end. In just three and a half years, the Nasdaq index had climbed nearly 200%. Stocks like Cisco, Dell, Juniper Networks, Yahoo and so many more rose into the stratosphere. (Cisco, for instance, gained 125,000% in the 1990s.) At the time, I lived in a hip college town in Massachusetts steeped in left-wing politics, yet my lefty neighbors were suddenly all talking about how much money they were making in the stock market.

So I decided to write a piece about how middle-class Americans had become obsessed with the market and how it was transforming investing. “Trader Nation,” the cover headline screamed. “At work, at home, all day, all night: Everybody wants a piece of this stock market.” My thesis was that individual investors were creating (to borrow from that cover language again) “a new set of rules.”

Oops.

Five months later the bubble burst. Those middle-class Americans, it turned out, hadn’t transformed investing after all; they had been caught up in a bubble and had lost a lot of money. No doubt there were those who saw it coming, but I wasn’t one of them. Neither were the millions of others. In theory, investors understood that dot-com prices were out of whack and that it had to end someday. Nonetheless, when it actually happened, people were caught by surprise.

It’s the same with the emergence of the coronavirus. As we begin this new week of market uncertainty, it’s worth remembering that when market conditions change, you rarely see it coming. This is partly because when we’re in a particular economic environment, especially one that has lasted a long time, we tend to forget that there was ever a time when it was different.

But it’s also because, more often than not, the thing that changes everything usually comes out of the blue — it’s a long tail event, or a black swan or whatever you want to call it — a risk so unlikely that it is beyond the realm of normal expectations. The coronavirus is a classic of the genre.

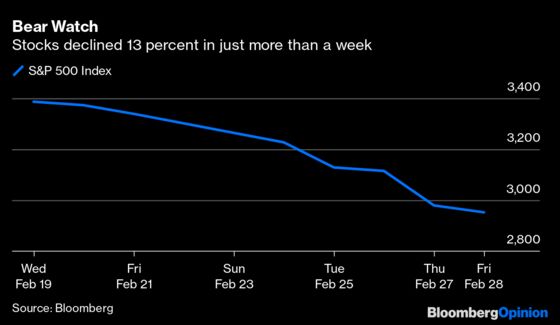

For nearly a decade, market indexes had been on an upward trajectory with only an occasional break. Then between Feb. 19 and Friday, the market dropped about 13 percent, putting it firmly in correction territory. Another week like last week and a bear market will be upon us. (Stocks did rebound on Monday.)

Did anyone see this coming? No. Even last December, when it first emerged that the Chinese city of Wuhan was suffering from an outbreak of the illness — and that the Chinese government had quarantined the city — it still didn’t seem possible that it could end a 10-year bull market. Again, we all knew it had to end someday — but nobody anticipated a pandemic might be the culprit.

In books like “Fooled by Randomness” and “The Black Swan,” Nassim Nicholas Taleb has made a nice living pointing out that Wall Street’s risk-management tools aren’t adept at anticipating black swans — not just pandemics, but tsunamis, nuclear accidents, assassinations and other rare catastrophes. The greatest risks, he believes, aren’t the ones you can see and measure but the ones you can’t see and therefore can’t measure.

But I think another factor is at play, which is the complacency that comes from living in a period that makes you forget that times were not always like this one. In the 1970s, the stock market was so dormant that BusinessWeek famously proclaimed “the death of equities” on its August 13, 1979, cover. The article noted that there were 7 million fewer shareholders than in 1970 and that chronic inflation “was destroying the stock market.” The authors wrote: “To bring equities back to life now, secular inflation would have to be wrung out of the economy.”

What BusinessWeek — and most of us — could barely comprehend was that inflation would ever be tamed. But Paul Volcker, who was appointed chairman of the Federal Reserve about the same time that article was published, did it. It took him a while, and he had to inflict a lot of economic pain on the country, but by August 1982 his actions led to a powerful 18-year bull market.

Or consider the subprime housing bubble. Mortgage underwriting standards fell away; Wall Street became addicted to buying and bundling subprime loans; homeowners abandoned safe and sound prime mortgages for subprime loans they couldn’t afford; ratings companies gave triple-A ratings to subprime mortgage bonds that were doomed to fail. All of these actions were predicated on the idea that housing prices could only go up — because, after all, that’s what they had always done. No one could imagine housing prices falling. And once they did, people on both Main Street and Wall Street were caught so unaware they had no time to prepare for the painful losses that would cost millions their homes, not to mention the failure of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers.

When Donald Trump was elected president, I was among those who thought his sheer economic ignorance would cause the market to crater. His use of tariffs as his weapon of choice would raise costs for U.S. businesses and consumers, which would be reflected in lower consumer spending and reduced profits. His disruption of cross-border supply chains would damage the economy. His eagerness to rid the country of immigrants would hurt agriculture, small manufacturing and other industries that relied on immigrant labor.

I was hardly the only one who thought this. The day after the 2016 election, Paul Krugman wrote: “So we are very probably looking at a global recession, with no end in sight.” But the Trump administration slashed corporate taxes while the Fed did its part to keep the market rising, and the Obama stock market morphed into the Trump stock market without a hitch.

It could be the thing we least expected that ends this bull market. Which just goes to show: You never know.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Joe Nocera is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He has written business columns for Esquire, GQ and the New York Times, and is the former editorial director of Fortune. His latest project is the Bloomberg-Wondery podcast "The Shrink Next Door."

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.