(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The art world has seen a lot of crazy in the past decade. With trophy assets booming in a low-rate world that drives demand for safe havens, only the clubby world of the super-rich and the brand power of Leonardo da Vinci could turn a $1,000 art-auction bet into the $450 million “Salvator Mundi.”

The digital art world now represents a slice of that excess. Hyped-up cryptocurrency-fueled collectibles, known as non-fungible tokens, are in gold-rush territory: More than $2 billion in NFTs have changed hands in the first three months of 2021, according to NonFungible.com. Bored, wealthy millennials are all too eager to flash their cash online.

As NFT advocates explain what separates these collectibles from the average JPEG, there’s one argument that keeps coming back: Transparency of ownership and authenticity. Colorful memes and epic multiyear online art collages may be easily reproducible, but, in theory, the NFT’s digital signature — often pointing to a link rather than the image itself — is not. That’s what gets collectors’ pulses racing.

You might call this principle the crypto world’s Da Vinci Code. It’s a cliche by now that every NFT fan, from electronic duo Disclosure to the buyer of Jack Dorsey’s minted first tweet, has to invoke the Mona Lisa.

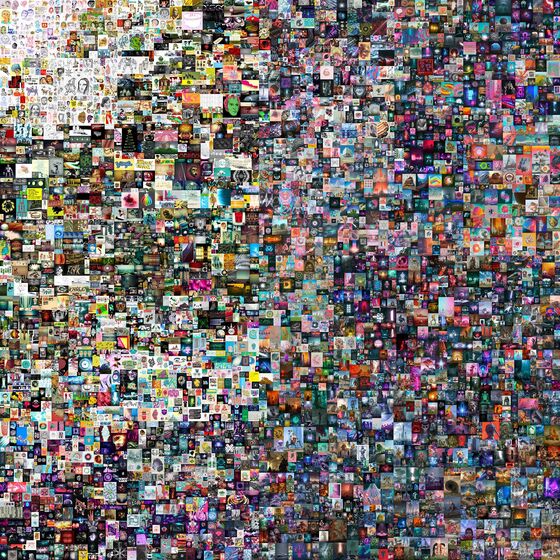

Just as the Louvre’s treasure has been pasted onto a gazillion postcards and posters without hurting the value of the precious original hanging on its walls, so NFT owners think their digital autograph will always have value. “The Mona Lisa is interesting because the physical piece represents the story,” said the buyer of Beeple’s digital magnum opus “Everydays: the First 5,000 Days.”

The irony of invoking the authenticity of an Old Master as a digital benchmark won’t be lost on fans of art critic John Berger, whose 1970s documentary series “Ways of Seeing” argued that the value of fine art in the age of instant photography had become all about authenticity.

Consider “Salvator Mundi,” deemed lost for years but authenticated by experts after its rediscovery in 2005, though not exactly unanimously. Even now, lingering doubts are making headlines again; a new documentary says they kept the Louvre from publicly giving its full seal of approval for a recent exhibition of the painting. The New York Times attributes the spat to pressure from the work’s Saudi owners to display it next to the Mona Lisa.

This matters because the more of the master’s original hand is deemed to be there, the more valuable it is. Hanging a painting by Da Vinci’s assistants in the royal yacht, or as the centerpiece of a new Middle Eastern cultural hub, isn’t quite the same.

Authentication is a battle waged through time and money. Yet the rhetoric of the NFT crowd sees art like Da Vinci’s as a permanent, eternal brand, and one perfectly reproducible on the blockchain. After all, this supposedly immutable ledger of transactions is promoted as a way to avoid squabbles over who painted what. But this isn’t a solution. NFTs often don’t point to an image but to a link, or metadata file, which still depends on the artwork existing separately on a server somewhere. We’ve already seen links go bad or digital images swapped out for others. NFTs’ lofty promises may not survive for 50 years, let alone 500.

The fragility of modern art isn’t a new concept. Preserving VHS tapes from the 1980s and 1990s is now a task for archivists. Maybe NFTs will be an incentive toward better digital storage, even as Beeple pushes back against the idea of physical art being more valuable: “I really wanna go legit, looking for printer recommendations," he joked. His work now hangs in a purpose-built virtual museum, perhaps a sign of the future.

Mona Lisa references don’t really clarify what exactly NFT buyers are getting. They also ignore the messy historical developments that led the Da Vinci portrait to become art’s global benchmark. It only really shot to fame in 1911, when it was stolen from the Louvre and sensationalized by the world’s press. Maybe it will take a theft of an NFT from a crypto-museum for investors to wake up to what's really valuable — even if it punctures bubbly prices.

The National Gallery’s later version was thought to be mostly the work of the artist’sassistants until 2010, when it was given a thorough restoration.

Saudi Crown PrinceMohammed bin Salman reportedly bought the painting via a surrogate at its record-breaking auction in 2017; the Times reports it belongs to the Saudi Culture Ministry.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lionel Laurent is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the European Union and France. He worked previously at Reuters and Forbes.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.