(Bloomberg Opinion) -- After several decades on the defensive, rent regulation has been on the comeback trail in the U.S. lately. In Oregon, the state Legislature and governor approved a new law early this year that limits rent increases to 7% a year plus inflation. In California, the state Assembly passed a similar cap in May that’s currently in committee in the state Senate, and local rent-control measures have been popping up on ballots for several years now and sometimes passing. In New York, which has the country’s best-known and most extensive system of rent regulation (with allowed annual rent increases of much less than 7% plus inflation), the state Legislature and governor this month enacted a set of changes that will, among other things, put an end to thousands of New York City apartments leaving rent regulation every year when they become vacant.

Proponents of rent regulation say it protects tenants in expensive markets, keeping families and senior citizens in their homes and preserving neighborhoods from rapid change. Opponents argue that such laws do nothing to increase the supply of affordable housing and sometimes decrease it, while leading to declines in housing quality. Interestingly, both sides appear to be right: Empirical studies examining a major expansion of rent control in San Francisco in 1994 and its abrupt removal a year later in Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts, found that removing controls led to higher rents on previously controlled apartments but also increased investment in housing quality and supply, while adding new controls conferred benefits to the affected tenants and caused them to stay in their apartments longer but reduced the overall supply of rental housing, thus driving up rents on unregulated units.

New York City has had no recent change in rent regulation quite sweeping enough for economists to build such a quasi-experimental study around. But the state Legislature did make a policy shift in 1993 to enable landlords to remove apartments above a certain monthly rent (originally $2,000, this year $2,774.76) from rent regulation when they became vacant or their tenants passed an income threshold (originally $250,000 a year, this year $200,000). The New York City Council made it easier for them to do so in 1994, and the Legislature loosened the rules even more in 1997. This month’s legislation repealed these high-rent-decontrol provisions. The New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey conducted every three years on the city’s behalf by the U.S. Census Bureau allows us to track what happened while they were in effect:

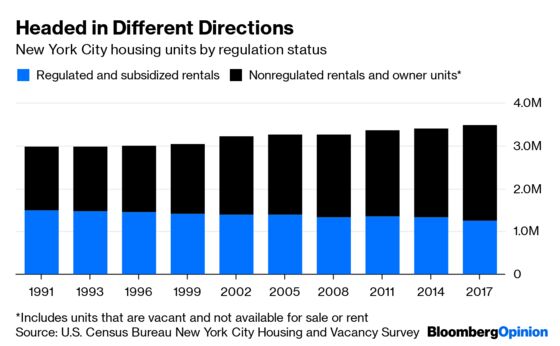

The number of New York housing units that aren’t subject to rent regulation has grown 49% since 1991; the number of regulated and subsidized units is down 16%. In 1991, the city’s housing stock was split about 50/50 between regulated housing and not; now 64% of units are unregulated. High-rent decontrol wasn’t the only cause of this shift, but it was a big one.

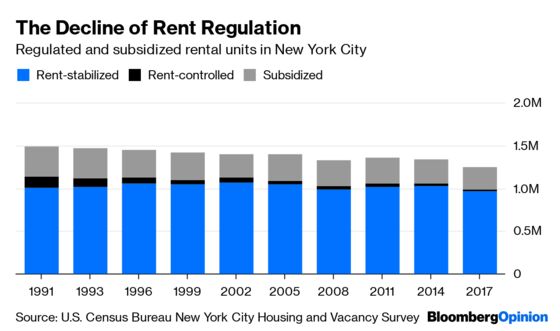

Rent regulation in New York consists of “rent control” and “rent stabilization” (though it exists in other parts of the state, I’m going to focus on New York City because that’s where the overwhelming majority of the regulated apartments are). Under both systems, rents can be increased within limits — which under rent control are determined by the largely incomprehensible Maximum Base Rent system and under rent stabilization are set annually by the New York City Rent Guidelines Board, which voted Tuesday night to allow increases of 1.5% for one-year leases and 2.5% for two-year leases in the 12 months starting in October. On average, rent-stabilized apartments cost about one-third more than rent-controlled ones. Rent control dates to the 1940s, applies only to buildings constructed before Feb. 1, 1947, and as of 2017 covered only about 22,000 units occupied either by people who’ve been in them since 1971 or by qualifying family members (kids, mainly) who succeeded them. Rent stabilization applies to buildings constructed before 1974, plus newer ones whose owners took advantage of tax breaks for new construction (the Section 421-a program) or extensive renovation (the J-51 program). Rent-controlled units also convert to rent-stabilized when they become vacant.

Rent control is dwindling away, as it is meant to do. The number of subsidized units — public housing plus several other kinds of government-backed apartments — fell by 27%, or 94,632 units, from 1991 to 2017. The number of rent-stabilized units has been far more stable, declining just 4% since 1991, although that still amounts to 44,142 fewer units.

The subtractions from the rent-stabilized housing stock in the above chart are partly offset by additions, most from the tax-credit programs. In 2017 and 2018, thanks to a permitting boomlet right before the expiration at the end of 2015 of the 421-a tax credit (a new version, called Affordable New York, was approved in 2017), there was actually a net gain in the number of stabilized apartments. But there was a net loss in every year before that, and high-rent decontrol has since 2000 been by far the biggest cause, although 2011 legislation that tightened the rules for landlords seems to have slowed things down a bit.

So what’s going to happen now? I would guess that the number of rent-stabilized apartments in New York will continue the upward trend of the past two years thanks to the end of high-rent decontrol and Mayor Bill de Blasio’s push for more affordable housing. But I’m skeptical that there will be all that noticeable an increase in the number of apartments that a household earning the city’s median income of $60,879 can reasonably afford: The number of government-subsidized units has been, as already noted, in steady decline, while the median monthly rent of apartments that joined the rent-stabilization rolls in 2018 (again, usually in exchange for a tax credit) was $3,000, or 59% of median household income.

The removal of vacancy decontrol will presumably reduce incentives for owners to push rent-regulated tenants out: As the New York Times detailed in a two-part series last year, some large landlords had developed aggressive “eviction machines” of legal actions and other tenant harassment to free up apartments for deregulation. It will also, along with changes in the law that limit rent increases due to major capital improvements, presumably reduce incentives for landlords to maintain and improve apartments, possibly reversing the long upward trend in New York City apartment conditions that saw 52% of renter-occupied units have no maintenance deficiencies in 2017, up from 38% in 1991.

Does this represent a reasonable trade-off for tenants? The consensus among economists, dating back at least to Milton Friedman and George Stigler’s famous 1946 pamphlet “Roofs or Ceilings? The Current Housing Problem,” has been that the overall economic costs of rent regulation outweigh the benefits to the tenants who are protected by it, and that affordable-housing policies focused on subsidizing tenants would be more effective. I’m sympathetic to this view, and was so even before I became (disclosure alert!) the indirect landlord of several rent-regulated New York tenants, but I have also come to believe that it’s pretty naive. Current tenants understandably prefer status-quo guarantees to hypothetical future subsidies, especially since — as is apparent in the long decline of of subsidized housing in New York — such subsidies seem to be even harder to maintain politically than rent regulations are. Rent regulation survives in part because the more efficient remedies that economists propose just don’t have the votes.

A 1995 California state law sharply restricts what local governments can do about rents, though, and voters last fall turned down a statewide ballot measure that would have overturned it.

Vacancy decontrol has been far more common than high-income decontrol, with 160,292 units leaving rent stabilization since 1994 due to the former and 6,455 due to the latter.

That is, my wife and I have been shareholders since 2013 in the cooperative association that owns our apartment building and the one next door, and also owns the remaining rent-regulated apartments within (this is contrary to standard New York City practice, in which an outside "sponsor" owns the regulated apartments).

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.