(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As growth rebounds, consumer prices are rising around the world. While most major central banks are probably months away from tightening monetary conditions, especially given the contagious delta variant, many are starting to mull when to stop pushing so much stimulus into the economy. For the European Central Bank, though, any change in direction is more distant than for its peers.

The ECB has flagged that it will change its forward guidance at its meeting this week, after a policy review that gives it room to allow inflation to overshoot its newly cemented target of 2%. A likely change in emphasis to actual inflation outcomes, rather than forecasts, means the current relaxed stance will need to last for even longer. That could set the scene for a renewed outbreak of infighting between the central bank’s hawks and the doves.

The euro zone’s economic prospects remain more reliant on loose monetary conditions because of the relatively muted fiscal response from the bloc’s governments to virus-imposed lockdowns. As Christopher Jeffery, head of inflation and rates strategy at Legal & General Group Plc’s investment division, recently put it, “There is little enthusiasm for abandoning European fiscal orthodoxy anytime soon.”

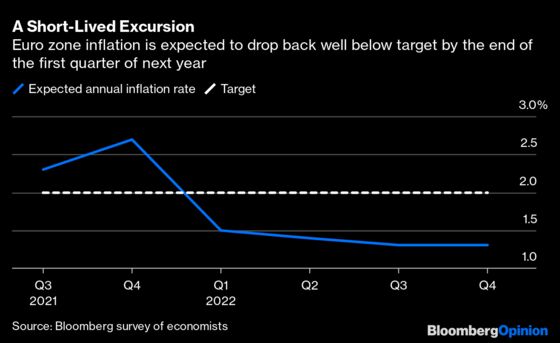

So the ECB’s tone is set to remain much more cautious about reining in its support programs. “We have to avoid tapering before the time comes that we’re really confident” that inflation will sustainably reach 2%, ECB Governing Council member Ignazio Visco told Bloomberg Television last week. Given the outlook for consumer prices to slump once again next year, that remains an aspiration at best.

In a handful of emerging markets, central bankers have already tightened. The monetary authorities in Russia, Brazil, Chile, Hungary, Mexico and the Czech Republic have all raised interest rates in recent weeks. It’s a timely reminder that rising prices bite faster and harder in poorer economies.

Among developed economies, the argument is mostly about when policy makers will take their foot off the accelerator, rather than when they’ll begin tapping on the brakes. But the debate about whether the current bout of global inflationary pressure will prove transitory or not is heating up everywhere, and rightly so.

The Bank of Canada, for example, last week reduced the scale of its bond purchases for a third time this year. It’s becoming less relaxed about its current attitude after consumer prices more than trebled since January, although it officially still expects to keep its benchmark interest rate unchanged at 0.25% through the middle of next year.

The Bank of England looks poised to make a quick switch away from maintaining the pace of its bond-buying program, with policy makers starting to shift to a more hawkish stance. Monetary Policy Committee members Dave Ramsden and Michael Saunders both suggested last week that they may be in favor of trimming the bank’s quantitative easing program in the coming months. An inflation rate that was expected to peak at 2.5% this year is now seen by some economists as approaching 4% before it calms back down. The alarm bells should start to ring in Threadneedle Street if prices are rising at twice the central bank’s target.

With U.S. inflation running at more than 5% last month, the Federal Reserve is coming under increasing pressure to consider curtailing its stimulus program. “I think we are in a situation where we can taper,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis President James Bullard told Bloomberg Television’s Michael McKee last week.

Cutting back on the pace of bond buying is a less aggressive withdrawal of stimulus than either shrinking central bank balance sheets or actually raising interest rates. But as the consumer price environment has shifted more rapidly than expected, so central banks have to become nimbler with their responses.

In New Zealand, for example, economists are starting to pencil in a rate increase as soon as next month. The spur? A surprise jump in the nation’s inflation rate to 3.3% in the second quarter, more than double the pace in the first three months of the year. It said on July 14 it will cease its bond-buying program by the end of this week.

That suggests the global central banking playbook currently anticipated by market participants, with bond purchases ending before official interest rates rise, still prevails. So investors should get plenty of warning before higher interest rates are on the cards, averting any bond market taper tantrums as policy makers scale back their support for fixed-income markets.

In Frankfurt, ECB chief Christine Lagarde has papered over the divisions between the bank’s hawks and its doves that have plagued the institution since the global financial crisis, but the wrangling is likely to resurface in the coming months. While its peers elsewhere start to return to a more orthodox stance, the euro-zone central bank needs its doves to continue to prevail unless and until the threat of deflation is finally vanquished. And that’s still a long way off.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Gilbert is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering asset management. He previously was the London bureau chief for Bloomberg News. He is also the author of "Complicit: How Greed and Collusion Made the Credit Crisis Unstoppable."

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.