Netflix Is Winning Streaming’s Own ‘Squid Game’

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Television fans have been willing to give just about every new streaming-TV service a shot. But “Squid Game” shows how Netflix Inc. has uniquely mastered the art of keeping its subscribers.

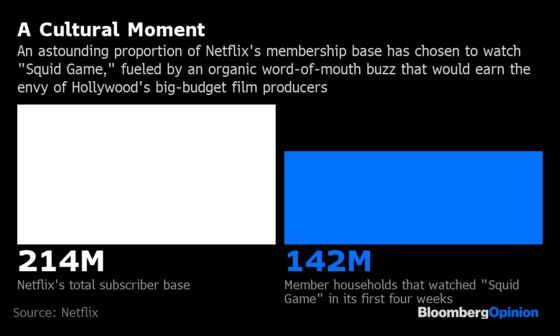

Netflix surpassed expectations Tuesday when it reported 4.38 million net new members for the third quarter, with a big boost coming from the Asia-Pacific region as the U.S. and Canada returned to growth. But even those results don’t fully reflect the “Squid Game” phenomenon of the last few weeks, which demonstrates perfectly how Netflix has turned serendipity into a dependable business strategy. It contrasts with the industry’s risk-averse fixation on familiar franchises and old reliables.

In mid-September, just before the quarter ended, Netflix released a Korean-language series featuring no globally recognizable actors and a violently dystopian storyline that was turned down by studios for years because it seemed too grotesque. And yet the enticement of a bizarre plot, mysterious title and hefty degree of FOMO has fueled “Squid Game” curiosity around the world, making it Netflix’s biggest series ever.

By early October, Netflix mobile downloads exploded. Apptopia estimates the app was downloaded 777,000 times on Oct. 4, the most so far this year. “Squid Game” has since been parodied on NBC’s “Saturday Night Live.” Imitation mobile games have topped the iPhone charts. And creepy series-themed costumes are expected to be everywhere this Halloween. “Squid Game” even showed up James Bond on his opening weekend in theaters. Because of the show’s success and a recovery from last year’s other Covid-19 production delays, Netflix projects app signups will accelerate to 8.5 million in the fourth quarter.

According to closely guarded internal documents that were unearthed by Bloomberg News this week, Netflix also estimates “Squid Game” has generated $891 million of “impact value.” What that means isn’t entirely clear: Netflix calculates something called an adjusted view share (AVS) based on viewership and the estimated value of those viewers; the lifetime AVS of a program becomes its impact value, Bloomberg reported.

That formula for deriving value in the absence of box-office ticket sales, advertising revenue or any other traditional measure of performance hints at how the industry may determine financial success in the future. It also shows how a series that might be seen externally as just a flash in the pan can instead be an important profit driver. For subscription services, the highest-returning investments are the productions that motivate a bored customer to get interested again rather than cancel.

In an attempt to translate Netflix’s metrics into a language investors can understand, Matthew Harrigan, an analyst for Benchmark & Co., estimated that the company acquired about 7 million members from “Squid Game.” Those users, should they never cancel, translate to $4 billion of value for Netflix, he wrote in a report earlier Tuesday. That’s equivalent to 1% of Netflix’s market capitalization.

Netflix has been criticized for not having enough enduring franchises like Marvel and Star Wars. Having those would certainly aid its efforts to expand into merchandise licensing, which is one of Walt Disney Co.’s highest-margin businesses. Still, while those franchises may have helped Disney+ get a lot subscribers out of the gate, its narrow focus could also limit the ultimate size of its subscriber base. Even for viewers who favor a specific genre, the overwhelming majority of their viewing time is spent on services with broad menus, according to a recent Parks Associates survey.

Netflix still expects free cash flow to break even this year. Even one of the stock’s biggest bears, Michael Pachter of Wedbush Securities Inc., estimates Netflix will generate an additional $1 billion of free cash flow each year to reach $9.4 billion by 2030. Disney’s business has thrown off about $6 billion a year on average for the past decade, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Streaming is an expensive business, and it will be difficult for Hollywood to replicate the favorable conditions that earned its riches in the era of cable TV and movie theaters. Now it’s all about keeping that one dangling subscriber from dropping off. Keep millions from doing so and companies like Netflix might reap billions.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Tara Lachapelle is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the business of entertainment and telecommunications, as well as broader deals. She previously wrote an M&A column for Bloomberg News.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.