Sometimes Investors Should Just Run for the Hills

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- If you’re an investor whose money is with a benchmark-lagging active fund manager (and that’s the most likely performance scenario in this area of money management) should you hold or fold? Often the answer is to bail out as fast as you can, as customers of Neil Woodford have learned to their cost.

Unsurprisingly Cambridge Associates LLC, a company that earns its crust managing funds and advising investors, warns that hasty withdrawals may mean their clients missing out on potential profits. Less predictably, Cambridge’s own data demolishes its arguments for sticking with faltering stock-pickers.

Cambridge, which manages about $30 billion and advises institutional investors such as pension funds and endowments with assets worth about $390 billion, publishes a yearly report on the performance of equity managers around the world. The one for 2018 is dismal reading.

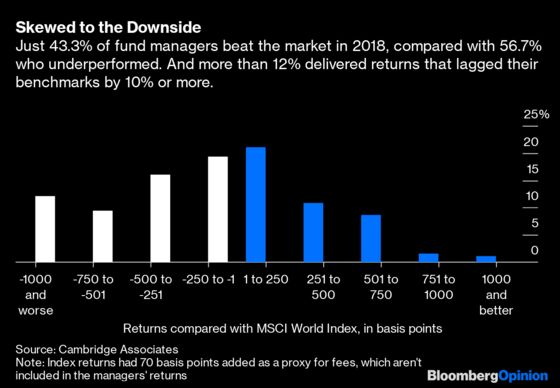

More than half of the 275 active fund management firms studied failed to beat their benchmarks last year. Just 11% outperformed by between 2.51% and 5%, while 16% lagged by the same margin. Most damning, more than 12% underperformed by 10% or worse. Just 1.1% delivered double-digit index-beating returns.

Woodford, one of Britain’s best-known investors, closed his firm this week after the administrators of his flagship fund fired him as its manager. His demise came after he loaded up on illiquid securities that proved too difficult to sell when investors demanded their money back. But his shift into unlisted and smaller stocks accelerated as he attempted to turn around the dismal performance of his portfolios.

So were investors right to stay with him? If all you read was the conclusion of the Cambridge Associates report, you might say yes:

Investors need to adopt a long-term view to get the best from active fund managers. A successful investing strategy requires very careful consideration before changing managers, even if that fund manager is suffering a period of poor performance.

The firm studied portfolio returns over the decade to the end of 2018, splitting the period into two five-year intervals. It celebrates the fact that 42% of the global equity managers who were in the bottom 20% between 2009 and 2013 subsequently rallied to rise to the top 40%.

What the text doesn’t say — but the data do — is that that the reverse was also true, with 47% of managers in the top 20% in the first five years sliding into the bottom 40% in the following half decade. How on earth could an investor know whether their particular underperforming fund would come good, or indeed whether their index-beating manager would slide down the rankings?

Rather than arguing, as Cambridge does, that the rebound of some managers proves “investors need to be patient,” surely it makes more sense to examine the market environment in which they were operating. That paints a different picture.

In the first half of the decade studied, the MSCI World Index roared ahead after an initial dip. Just being longer of stocks than indicated by the benchmark would have guaranteed outperformance in the five years through 2013. In the second half, however, life was much harder, with the MSCI’s performance basically flat for two years before struggling to build steam and eventually tailing off into a decline in 2018.

There will always be active managers who can beat their benchmarks. But telling in advance which stock-pickers will deliver sufficient outperformance to justify their fees versus a cheap index tracker seems like unattainable knowledge. The decision on whether to stay with a struggling manager would seem to rest mostly on whether the market conditions in which they beat their benchmarks will return.

But if you knew what markets were going to do in advance, you wouldn’t need to be paying someone to manage your money. You’d be enjoying your riches on your yacht, in the company of your crystal ball.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Gilbert is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering asset management. He previously was the London bureau chief for Bloomberg News. He is also the author of "Complicit: How Greed and Collusion Made the Credit Crisis Unstoppable."

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.