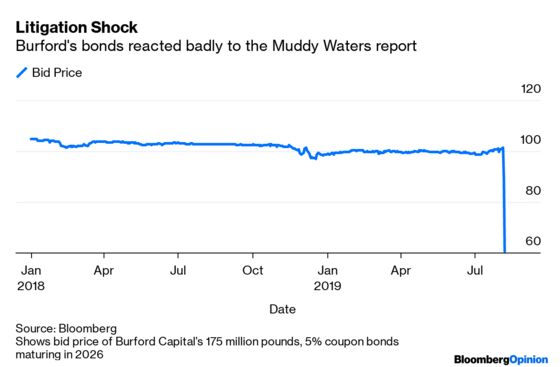

This week has been more sobering. On Wednesday the shares lost more than half of their value after Muddy Waters published a note casting doubt on the company’s seemingly stellar performance. Almost 2 billion pounds ($2.4 billion) of investor wealth has gone up in smoke since rumors of the short-selling firm’s interest first emerged on Tuesday.

That tells you shareholders think London’s more lightly regulated Aim market faces yet another potential accounting scandal. Retail investors who once queued up loyally to buy the stock have been badly hurt. Neil Woodford, the well-known U.K. fund manager who froze his flagship fund in June, is a major backer.

At the time of writing, Burford – which provides capital to clients pursuing commercial litigation – hadn’t had time to provide a full rebuttal of the claims made in the very detailed Muddy Waters report. But it said its returns were robust and that its accounting had been very detailed and consistent for many years. Its executives are mostly senior litigators so one might expect a fairly strong response later.

Still, the negative sentiment could be difficult to shift because Burford’s business is somewhat opaque and its approach to valuing legal cases is pretty subjective, something I explored in a column last year.

Such a sudden share price implosion will raise questions too about whether an inherently complicated litigation finance specialist is suited to the public markets, and if it is then how can it provide the necessary transparency – a shift to the main market might help. To restore confidence it also needs to comprehensively refute the allegations and rethink its unconventional corporate governance.

The crux of the problem is that rather than value its investments in fighting legal cases at cost, as some of its peers do, Burford uses an approach known as fair value accounting. The traditional notion of fair value is based on the price you could get for an asset – in this case a particular legal case – if you sold it in an open market. But how do you do this with a litigation? There isn’t a very active market for trading legal cases (although Burford has tried to create one), the cases can take years to conclude and the final outcome is inherently uncertain.

So-called unrealized gains – essentially cash that hasn’t yet been booked but which the company expects as a result of positive court rulings or settlement offers – have often made up about half of the company’s reported income in recent years.

Calculating Burford’s internal rates of return and returns on invested capital, which are important metrics for investors, also involves a degree of subjectivity about what should be included. Portia Patel of Cannacord Genuity, the only equity analyst with a sell rating on the stock, highlighted this in a note earlier this year.

The company’s auditors, Ernst & Young, acknowledge the risk that the fair value might be inaccurate. They try to remedy this by conducting external research and engaging independent counsel to double-check the assumptions. Still, the assessment of fair value by Burford’s management ultimately affects the earnings it reports.

The company says shareholders shouldn’t rely on earnings projections from research analysts because of how difficult it is to forecast accurately its investment income. So trust in the leadership is paramount for anyone investing in this particular stock. Unfortunately, Burford doesn’t help its own cause by having rather lax governance.

It’s unusual, to put it mildly, that the firm’s chief executive and co-founder Christopher Bogart is married to its chief financial officer Elizabeth O’Connell. Meanwhile, the company’s four independent directors have held office for the entirety of Burford’s near 10 years as a public company.

Burford doesn’t have much debt and more than $400 million of cash and equivalents provides a short-term buffer. However, its ability to borrow and raise equity capital cheaply – something it has done often to fund new cases and expand – could be tested unless it can calm nerves decisively. More independent board members would be a start.

With dividends reinvested

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.