(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Two months ago, I wrote a column with the headline “Don’t Expect Mortgage Rates to Drop Much More.” At the time, the average for a 30-year fixed loan was near its record low of 3.23% but still much higher than what might be expected, given the going yield of 0.7% on benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasuries.

Even as mortgage rates continued to slide in the following weeks, to 3.15%, then 3.13%, I was confident that my thesis would hold up and the spread between the two rates would remain historically wide. After all, the 10-year Treasury yield had dropped by eight basis points during that time as well.

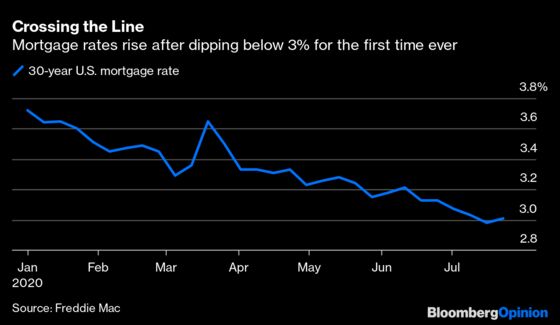

July was shaping up to be a different story. In the three weeks through July 16, the 30-year mortgage rate tumbled in each period, from 3.13% to 2.98%, marking the first time in 49 years of Freddie Mac data that it fell below 3%. Treasury yields, by contrast, had only dropped by a few basis points. The difference between the two was on pace to reach the narrowest since February, before the coronavirus pandemic. Perhaps I underestimated the mortgage market’s ability to recalibrate.

Then, at last, it hit the 3% wall. Mortgage rates in the U.S., as measured by Freddie Mac, increased last week for the first time since early June, climbing to 3.01%. Bankrate.com’s measurement also ticked higher, to 3.15% from a record-low 3.13%. All this, even though Treasury yields were grinding ever-lower.

So what is going on here?

At a high level, housing demand is unusually strong. Purchases of previously owned homes posted their largest monthly advance on record in June, according to data last week from the National Association of Realtors. Meanwhile, purchases of new single-family houses raced to an almost 13-year high in the same month, exceeding all economists’ forecasts. Those data points were backed up by quarterly results from PulteGroup Inc. that showed home orders for June jumped 50% from a year earlier, led by a spike in first-time buyer interest. Given that the company tends to focus on more expensive homes than its peers, it supports the theme of white-collar workers who previously rented in large cities opting for more space to work remotely in the suburbs.

On top of that, homeowners have shown a renewed interest in refinancing, with the share of refis as a percentage of total applications climbing to a 10-week high as of July 17, according to MBA data. The rate falling below 3% might have “set off alarm bells” for those who hadn’t been paying attention before, Mark Vitner, senior economist at Wells Fargo Securities, told Bloomberg News’s Prashant Gopal. In March, the droves of people looking to lower their mortgage rate created a backlog and allowed originators to retain pricing power. They could very well be holding firm now at 3%, especially if they’re scaling back their risk tolerance given the uncertain economic outlook.

It’s hard to prove definitively that 3% is a “line in the sand” in mortgages, particularly when interest-rate records are shattered across financial markets (see investment-grade corporate bond yields at 1.89%, for instance). But one way to test this theory is by incorporating yields in the mortgage-backed securities market, in addition to the 10-year Treasury rate. As William Emmons, lead economist with the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’s Center for Household Financial Stability, wrote in a report last month, this creates two distinct spreads that reflect both the retail and wholesale portions of the overall mortgage market:

Most mortgage originators — especially those that are not banks — operate like brokers or dealers in mortgages. That is, they keep one eye on the wholesale market — the prices paid by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac for mortgages — and the other eye on retail mortgage-market conditions. This is known as the “originate-to-distribute” model of mortgage lending, in contrast to the “buy-and-hold” model of mortgage lending that was the norm 50 years ago.

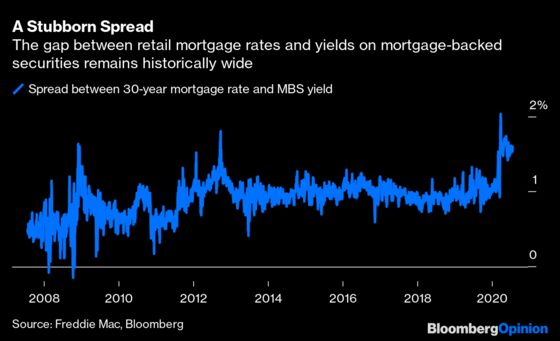

The retail mortgage market generally is very competitive, so the difference between the Freddie Mac Survey 30-year mortgage rate (the retail price) and the yield on Fannie or Freddie mortgage-backed securities (the wholesale price) reflects the gross profit margin available to a mortgage originator. This must cover marketing costs, short-term financing costs, other overheads and compensation for risk; net profit is what is left over.

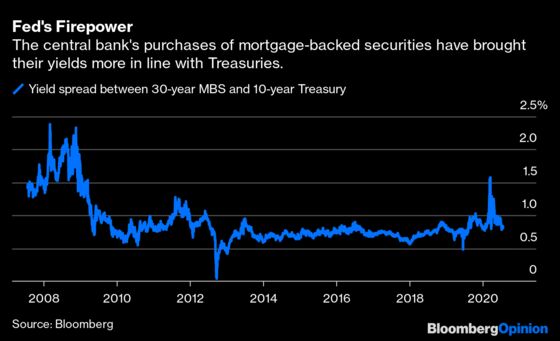

Even without knowing the exact fixed costs, it’s clear that for whatever reason, mortgage originators have not gone back to business as usual by any stretch. That’s in stark contrast to the MBS market, where the Fed is actively buying billions of dollars of debt each month to bring yields in line with their historical spread to Treasuries.

Here’s a chart dating back to 2007 that shows the spread between the headline 30-year mortgage rate (3.01%) and the benchmark 30-year MBS yield (1.43%). At about 160 basis points, it remains almost twice the historical average and higher than just about any time during the record U.S. economic expansion:

By contrast, here’s the spread between that same 30-year MBS yield (1.43%) and the 10-year Treasury yield (0.59%). Thanks to swift central bank intervention, that difference is now just 84 basis points, lower than the historical average and a smaller gap than what was seen in the final months of 2019:

In that June report, Emmons at the St. Louis Fed concluded that the historically wide primary-market spreads should revert to a more normal level “in the near future,” which could push the 30-year mortgage rate down 50 basis points or more. Instead, that gap has widened slightly since mid-June, while the secondary-market spread has dropped by about seven basis points.

Now, it’s still early days in this most unusual economic downturn, and perhaps it’s only a matter of time before mortgage originators capitulate and steadily offer rates lower than 3%. But the business has never faced long-term U.S. yields this low before. It’s telling that the lowest coupon on a 30-year MBS is still 2%, while the U.S. Treasury has auctioned 30-year bonds with 1.25% coupons for months.

JPMorgan Chase & Co. Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon, in typical fashion, launched into a monologue against mortgage regulations during the bank’s second-quarter earnings call earlier this month. He said the reason mortgage rates aren’t 1.6% or 1.8% “is because the cost of servicing and origination is so high, it’s obviously got to be passed through — it’s high because enormous amount of rules and regulations are put in place that do not create safety and soundness.”

On the one hand, the subprime mortgage crisis is still fresh in the minds of the Fed and other financial regulators, so it seems unlikely to expect a drastic loosening of rules around lending. And yet lower mortgage rates are a crucial way that easier monetary policy reaches the American public. The central bank’s asset purchases have mostly done what they can by normalizing that secondary-market yield spread between MBS and Treasuries.

That suggests the next leg lower in mortgage rates would have to come from originators settling for less than 3%. It’s hard to imagine that happening on a widespread level, given the murky economic outlook. Banks, for their part, are clearly bracing for turbulence ahead, with some $35 billion set aside for bad loans.

Put it all together, and the conclusion is the same as it was months ago: Barring an unexpected change in regulations or a way past the coronavirus pandemic, this looks as if it could be about as good as it gets for mortgage rates.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.