(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The number of refugees crossing the Mediterranean has fallen sharply since 2015, but the subject of immigration continues to scar public debate in Europe.

Parties of the far right, such as Italy’s League and France’s National Rally, argue that the European Union cannot afford to open its borders because jobs and welfare protection should go to natives first. Many economists argue the opposite, correctly in my view, saying that immigration is essential to helping to solve the EU’s demographic crisis.

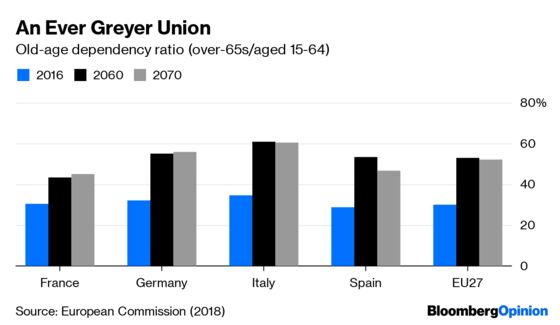

According to the European Commission’s 2018 “Ageing Report,” there will be only two people of working age for each retiree in the EU (excluding the U.K.) by 2060 – down from more than three in 2016. Young migrant workers will be necessary if Europe’s governments want to keep raising enough taxes to pay for hospitals, social care and pensions.

A debate at the yearly European Central Bank conference in Sintra, Portugal, provided useful evidence on this vexed question of whether immigrants are needed to help the EU stay young. The answer is that while their positive role shouldn’t be overestimated, there are few viable alternatives.

Axel Borsch-Supan, an economist at the Munich Center for the Economics of Aging, has looked in detail at Germany. He estimates that the old-age dependency ratio (the number of German retirees for each person of working age) will climb from about 0.35 to more than 0.60 between 2016 and 2060 if the country’s net migration stays at its long-term average of 200,000 arrivals per year. Keeping it constant at 0.35 would require an average net migration of about 1.2 million people a year for the next 15 years.

These projections appear to prove that Germany – and the EU more broadly – need many more migrants than are allowed in today. But politics won’t permit this. In 2015, Angela Merkel, Germany’s chancellor, opened the door to nearly 1 million refugees, winning global praise but prompting a backlash at home that has encouraged the rise of the far right Alternative for Germany (AfD) as an electoral force.

Merkel has since agreed to a refugee cap of 200,000 a year, and the number of registered asylum seekers has fallen from about 890,000 in 2015 to approximately 162,000 in 2018, according to Germany’s Interior Ministry. Of course, asylum seekers are only one type of immigration. Many people move for economic reasons. Overall net migration in Germany was slightly more than 400,000 people in 2017. While this is high by historical standards, it’s substantially lower than 2015’s 1.14 million increase. After the voter reaction to Merkel’s 2015 initiative, it’s hard to imagine Germany accepting many more newcomers than it’s doing now.

While politics stands in the way of immigration, the alternatives for defusing the demographic time bomb are unconvincing. Borsch-Supan believes that the replacement of labor with capital will boost productivity and help sustain economic growth even as the dependency ratio rises. But this won’t fill all of the gap. A new baby boom – which right-wing parties often advocate – would demand profound cultural change and would take about two decades to show any effects (the time for children to reach working age). In Germany, the total fertility rate would need to climb from 1.6 to 2.1 to stabilize the dependency ratio at 0.50 – well above where it is now.

Another argument in favor of immigration is that it could cause some interesting second-round effects, according to Anna Maria Mayda, an economist at Georgetown University. Her most interesting idea is that low-skilled immigrants can do childcare, housework and look after ageing parents, freeing up highly-skilled women to go back to formal employment. This would be especially helpful in countries like Italy with a low female labor force participation.

Studies have shown too that immigrants have a positive effect on innovation, which in turn boosts productivity – even though this depends on the skills of the migrant workers and may require substantial investment into education.

What’s inescapable is that Europe’s demographic problem can’t be solved with the amount of yearly immigration with which voters are comfortable. To adapt to their ageing populations many EU governments will have to pass unpopular pension reforms, further raising the retirement age, while companies will need to better accommodate older workers. But welcoming in more migrant workers will avoid even bigger generational imbalances. While Europe’s far right don’t want to hear this, it’s the truth.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Ferdinando Giugliano writes columns on European economics for Bloomberg Opinion. He is also an economics columnist for La Repubblica and was a member of the editorial board of the Financial Times.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.