Credit Ratings Firms Were Asleep at the China Switch

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Don’t you hate that type: Always late to the game but, once there, they play so aggressively to make up for it that everyone else gets scared. That’s not good sportsmanship.

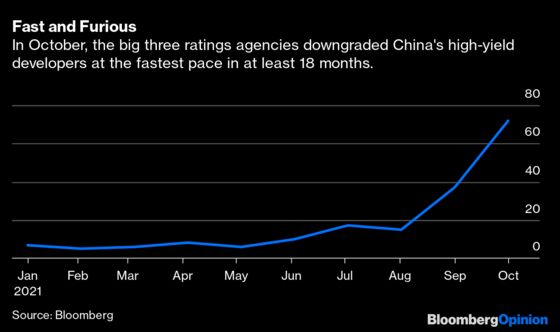

That describes what the big three international credit ratings firms are doing. Moody’s Corp., S&P Global Ratings and Fitch Ratings Inc. are downgrading China’s real estate developers at the fastest clip in over a year.

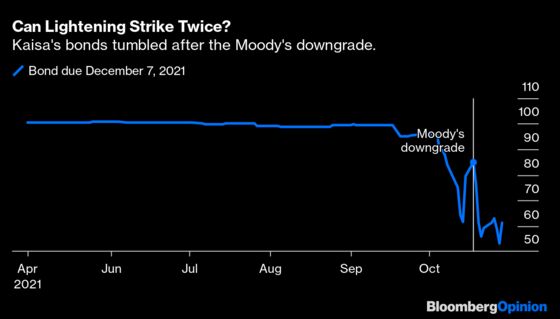

As downgrades escalate, traders panic. To meet their own compliance requirements, private banks rush to slash loan-to-value ratios of the degraded companies, triggering margin calls and prompting wealthy clients to sell at a loss. In this high-yield bond world, a lot of holdings were bought on credit by the ultra-rich who can borrow cheaply.

In recent days, to justify their actions, the firms pointed to developers’ mounting refinancing risks. But have they thought that this wave of downgrades may make it even harder for the issuers to refinance? On average, there is a 3 percentage point price drop to the issuers’ bonds two days after a rating action, according to HSBC Holdings Plc, which looked at 36 recent downgrades.

Take Shenzhen-based Kaisa Group Holdings Ltd. On Oct. 18, upon the Moody’s downgrade over its “refinancing risk,” Kaisa, the second largest issuer after China Evergrande Group, became the latest pressure point. The developer defaulted on its dollar-denominated debt in 2015 but nonetheless came back from the grave and miraculously cleared China’s so-called “three red lines.” Now, it is distressed once more thanks to the ratings firms. Lightning might just strike Kaisa twice. It’s almost a self-fulfilling prophecy.

To remain relevant, the ratings firms have to act, and act quickly. They are dealing with a worsening sentiment in China’s high-yield dollar-denominated bond space that started in early June. That’s when media reports spread that Beijing was looking into alleged related-party transactions between Evergrande and a regional bank it owned. By early October, we saw the worst selloff in at least a decade after Fantasia Holdings Group Co., one of the smaller developers, chose not to repay a bond, even though it had the money, or at least gave the impression of having it. In other words, the firms need to play catch-up to match their ratings to market pricing.

But one does wonder: Where were the ratings firms when the developers’ fate began to go sour? For many months, there was hardly any downgrade action despite the introduction of the three red lines policy in August 2020, which Beijing uses to decide who gets to borrow. In fact, we observed more ratings upgrades than cuts at the beginning of 2021. For instance, Moody’s upgraded Seazen Group Ltd. in January, while S&P followed suit in March. Seazen’s $400 million bond due next June now yields 16.7%.

Granted, China’s real estate developers are complex. Pinched by Beijing’s strict debt diet, developers did a lot of shadow banking, guaranteeing private bonds that are not on their balance sheets. Nonetheless, Fitch’s Oct. 4 decision to cut Fantasia’s ratings, complaining that “in a recent call” it heard “for the first time” about the existence of a $150 million private bond, is not good enough. We all know how to read balance sheets. We need ratings firms to dig up the dirt for us.

When the dust settles, the big three ratings companies need to do some soul-searching. What’s their role in the opaque bond world? Are they here to warn and inform? Or are they just going to exacerbate selloffs?

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.