(Bloomberg Opinion) -- There are those who complain that the U.S. has lost a lot of its regional distinctiveness. “It wasn’t just the coffee shops — bars, restaurants, even the architecture of all the new housing going up in these cities looked and felt eerily familiar,” journalist Oriana Schwindt wrote last year after voyaging through every state. “Oh, and breweries. Thousands of breweries, springing up in recent years like mushrooms after a rain.”

These observations generally accord with what I saw during a cross-country trip of my own last year. In the case of breweries, they’re also backed up by some pretty amazing statistics. There were 7,450 breweries in the U.S. in 2018, according to the craft-beer trade group the Brewers Association, up from 1,574 in 2008 and 89 in 1978. The number of jobs at breweries jumped from 26,380 in 2008 to 77,902 in 2018, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

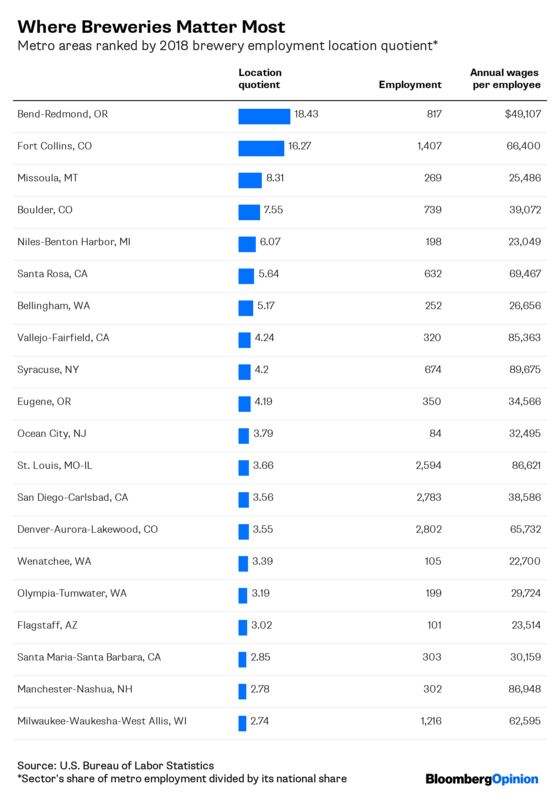

There is, however, still regional variation to be found. Yes, every city has a microbrewery and/or brewpub now, but some cities have a lot more microbreweries relative to their size than others. As I was looking through the above-mentioned BLS data for a Bloomberg Businessweek charticle about the brewery boom, I realized there was a handy way to sort this out: the “employment location quotient” that the BLS provides for states, metropolitan areas and counties in every industry. It measures an industry’s share of total jobs in an area divided by its share nationwide. In Bend-Redmond, a scenic and fast-growing metro area (estimated 2018 population: 191,996, up from 157,733 in 2010) just east of the Cascade Range in Oregon, one is effectively 18 times more likely to run into a brewery worker than in the country as a whole.

These data are from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, the hyper-detailed jobs report that the Bureau of Labor Statistics compiles from state unemployment insurance data. The QCEW doesn’t get nearly as much media attention as the survey-based monthly employment report because it comes out with a six-month lag, but man, is it illuminating. One important caveat: The QCEW gets so detailed that the BLS often has to suppress data so as not to reveal employment and wage information that can be traced to a single employer. Brewery employment data from the Chico, California, metropolitan area, home to the country’s third-largest craft brewer, Sierra Nevada Brewing Co., are suppressed. The largest craft brewer, D.G. Yuengling & Son Inc., is in Pottsville, Pennsylvania — which isn’t in a metropolitan area; plus, the BLS suppresses its county’s brewery employment data.

So the above table isn’t definitive, but it still gives a pretty good picture of where the brewing boom is concentrated: scenic Western cities, and some other places. Bend-Redmond boasts the 10th-largest craft brewer, Deschutes Brewery Inc., and 29 others, according to Beer Me Bend. Metro Fort Collins has the fourth-largest craft brewer, New Belgium Brewing Co. Inc., an outpost of the top U.S. brewer overall, Anheuser-Busch, and at least 35 other breweries, according to the BLS. The metropolitan areas that are home to the top-selling non-craft U.S. beers — Denver (Coors), Milwaukee (Miller) and St. Louis (Budweiser and the other Anheuser-Busch beers) — all remain major beer employment centers, although Denver owes its status as the nation’s No. 1 metro area for brewery jobs at least as much to the more than 100 non-Coors breweries in the area. (Anheuser-Busch is owned by Belgium-based Anheuser-Busch InBev SA/NV, Coors and Miller by MillerCoors LLC, the domestic arm of Denver-based Molson Coors Brewing Co.)

Pay tends to be higher at big breweries than at small ones, in part because all of Anheuser-Busch’s 12 “flagship breweries” are unionized and most of MillerCoors’s are. All the metropolitan areas with annual brewery wages of $80,000 or more in the above chart are home to major Anheuser-Busch breweries.

In the craft-beer mecca that is metropolitan San Diego, which according to the San Diego Brewers Guild currently has 128 breweries, wages are low but employment has more than doubled since 2014. The area was No. 2 in brewery jobs in 2018 and seems destined for the top spot. The giant Los Angeles metropolitan area is No. 3 but didn’t come close to making the above chart; it has a brewery employment location quotient of less than 1.

Brewing is of course not what one could call a huge industry. Even in the beer-sodden Bend-Redmond area, breweries account for only 1% of total jobs; nationwide, it’s 0.05%. But the BLS QCEW Data Viewer can also be used to look at bigger industries and broader categories, and discover some important things about U.S. economic geography. I recommend trying it out yourself if you’re interested, but I plan to do separate columns on what the latest QCEW data (released early this month) reveal about employment in finance, health care and a couple of other sectors. Also, if you’re into consuming artisanal beverages and such, you really should visit Bend, which also has high employment location quotients for coffee and tea manufacturing, medicinal and botanical manufacturing, and mobile food services.

Coming Saturday: The most finance-heavy local economies.

Having gone on similar road trips in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when most of the country’s downtowns seemed near death, I see these developments in a more positive light than Schwindt does. But that's another story.

The "flagship" is to differentiate them from the many craft breweries the company has acquired in recent years, most of which aren't unionized.

For time series you're better off on the QCEW databases page.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.