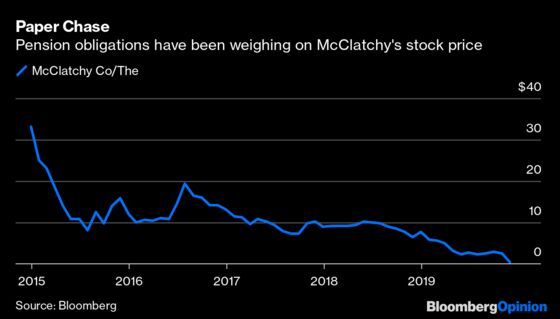

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- When I interviewed Craig Forman, the chief executive officer of McClatchy Co., last week, shares of the regional newspaper chain stood at 39 cents. Like its peers, it has struggled as print advertising has dwindled and subscribers have abandoned ship. Last month, the company said in a regulatory filing that it might not be able to continue “as a going concern” because of a pension overhang. That explains the depressed stock price.

Coincidentally, last month was also when Alden Global Capital LLC bought a 25% stake in another struggling media company, Tribune Co. As I’ve noted before, the Alden Global business model is to treat newspapers as declining assets and bleed them for cash until there’s nothing left but a carcass. It will no doubt be imposing its draconian business model on the Chicago Tribune, the Baltimore Sun and the other Tribune papers.

Meanwhile, in August, the New Media Investment Group announced that it was buying Gannett Co. and combining it with its GateHouse Media subsidiary, which instantly created the largest newspaper chain in the country. New Media is controlled by Fortress Investment Group, and its approach is not terribly different from Alden Global’s. People are starting to call papers owned by hedge funds “ghost papers” — defined by the New York Times as “thin versions of once robust publications put out by bare-bones staffs.”

Although they’ve had their share of layoffs, McClatchy’s 30 media properties, which include the Miami Herald, the Kansas City Star and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, are not ghost papers. A little more than a year ago, Julie K. Brown, a journalist at the Miami Herald, published an extraordinary expose of the convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein; that series sparked an outcry that led to Epstein’s arrest in July. In October, the well-regarded McClatchy Washington bureau documented a disturbing rise in the rate of cancer treatments at Veterans Affairs hospitals. And just a few weeks ago, the Kansas City Star published a powerful examination of Missouri’s public defender system.

“We are still determined to do essential journalism of genuine impact in our communities,” Forman told me in an email a few days before we met.

The “death of local news” has become a meme among journalists. According to a study by University of North Carolina researchers, 1 in 4 papers has shut down since 2004. Newspaper employment has been cut in half. Combined weekday circulation has shrunk from 122 million to 73 million. The New York Times ran a series of articles over the summer called “The Last Edition,” which examined “the collapse of local news in America.”

But Forman believes that, notwithstanding that 39 cent stock price, McClatchy can beat the odds and craft a model that will allow it to avoid the clutches of a rapacious hedge fund. In fact, he says, that’s what McClatchy is doing. That’s what I wanted to talk to him about.

To be clear-eyed about this, it will be not be easy. In 2006, with industry-wide circulation already in steep decline, McClatchy bought another regional chain, Knight Ridder, for $4.5 billion. When the deal was completed, McClatchy was saddled with $5 billion in debt. (The “ball and chain of debt,” Forman called it when we spoke.) The company has to pay $124 million into its pension in 2020 — cash it doesn’t have. In the first three quarters of 2019, its adjusted earnings were a slim $64.9 million. Its revenue has declined 27 consecutive quarters on a year-over-year basis.

On the other hand, McClatchy has reduced its debt from $5 billion to $700 million and has pushed off further payments to 2026. McClatchy family members haven’t received a dividend in a decade. And it is negotiating with the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. to take over its pension, which holds $1.3 billion in assets. These three moves — assuming the latter happens — will free up the cash McClatchy needs.

To do what, exactly? Forman’s goal is to complete a digital transformation that will allow McClatchy to thrive again by going from a business that relies primarily on advertising to one that relies mainly on digital subscribers, just as the New York Times and the Washington Post have done so successfully.

That may sound obvious, but no other regional chain has been able to accomplish it. That is partly because most of them were too busy cutting costs as revenue fell to spend the millions it would take to create a winning digital platform. And it’s partly because most of them lacked the scale to take full advantage of the ways digitalization could help revive them.

“It’s not just about putting your content on a website,” Forman told me. “Any digital effort has to be centralized.” A sophisticated digital platform is far too expensive for any one of McClatchy’s papers to do on its own — it has to be done companywide. If done right, it offers data analysis and analytics, targeting of potential customers, site personalization and so on.

Because McClatchy lacked a robust digital infrastructure during the 2016 election, “we mostly missed the Trump bump,” Forman said. The New York Times and the Washington Post have signed up millions of digital subscribers since the election. McClatchy hasn’t.

“We have newspapers in much of purple America,” Forman said, pointing to states such as Florida and Georgia where Democrats suddenly have at least a fighting chance. “That’s where the 2020 election is going to be decided.” This time, he wants McClatchy to be ready to offer digitized political news to a national audience hungry to consume it.

That may help on the margins, but for a company like McClatchy, the core subscriber is still going to live in the 30 metropolitan areas its papers serve. Forman told me that the top five categories McClatchy’s readers want are local opinion, breaking local news, sports, news-you-can-use service articles and investigations. That’s what his papers are trying to deliver. “You have to be essential to your community,” he said. The papers run by hedge funds have largely lost that ability because they are too thinly staffed. McClatchy is betting that high-quality digital journalism will be a winning strategy.

So far, McClatchy has 200,000 digital subscribers and nearly 500,000 “paid digital relationships,” which include print subscribers who have activated their digital accounts. This year, for the first time, its revenue is split 50-50 between subscriptions and advertising. But given that the chain’s total circulation is close to 1 million (1.3 million on Sundays), it has a long way to go.

“We’re in a race,” Forman told me. A race against the debt that will come due in six years. A race against the 2020 election that could boost its digital fortunes. A race to replace advertising dollars with subscription dollars while there’s still time.

Forman and McClatchy are running as fast as they can.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Joe Nocera is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He has written business columns for Esquire, GQ and the New York Times, and is the former editorial director of Fortune. His latest project is the Bloomberg-Wondery podcast "The Shrink Next Door."

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.