Markets Without Havens Are Becoming All Too Real

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In Lewis Carroll’s classic children’s book, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass, Alice says, “If I had a world of my own, everything would be nonsense. Nothing would be what it is because everything would be what it isn't.” For financial market participants, that world Alice envisioned has become a reality.

After almost two decades of quantitative easing by the world’s major central banks, investors find themselves deep down the rabbit hole. The more than $16 trillion of bond and stock purchases by central banks since the financial crisis alone has artificially boosted asset prices. Although these purchases bolstered confidence in the financial system, they failed to achieve their primary goal, which was to spark faster inflation.

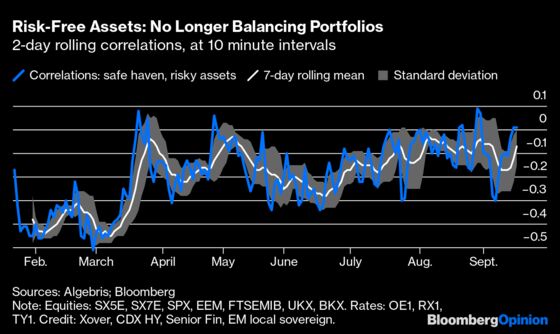

Another important thing has happened, and that is haven-like assets are no longer much of a haven. We have witnessed some rather unprecedented market moves in recent months, with government bonds falling along with equities with increasing regularity. In a repeat of 2018, the correlation between haven and risky assets went positive at times. This should really come as no surprise. With central bank purchases flooding the financial system with cash, the "buy everything" trade was the right thing to do.

But if all financial assets move in tandem, true portfolio diversification becomes hard to achieve. At the least, a traditional portfolio made up of 60% equities and 40% bonds is no longer a valid strategy. A market where everyone buys or sells at the same time is a fragile market. It is fine as long as monetary policy remains expansionary, but when inflation finally starts to accelerate and central bankers turn less accommodating, like in 2018, then investors in all types of assets run for the same exit at the same time.

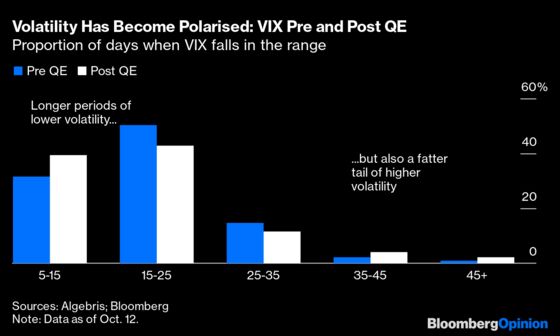

Although volatility has collapsed in the era of quantitative easing, in those periods when it has increased, it has generally risen unusually fast and created much pain for investors. Take the CBOE Volatility Index, or VIX. Even though it is more likely to stay below 20 these days, it is twice as likely to surge above 40 when it does rise. It doesn’t help that passive investment strategies make up half of all share trading, twice as much as 10 years ago, meaning there are fewer humans at the helm to make rational decisions when markets go haywire.

What’s more, market makers hold a tenth of the trading inventories they had in 2007, according to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. As a result, they are unable to act as a sort of market shock absorber during periods of rapid price swings like they had in the past. That combined with capital flocking in and out of the same trades means markets are breaking down more often.

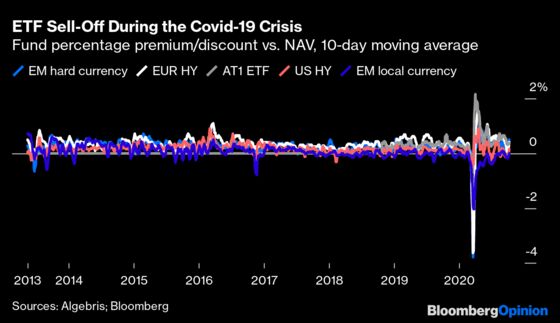

A good example comes from March, when exchange-traded funds owning investment-grade corporate bonds experienced price declines exceeding 10%, dropping 4% to 5% below their net asset values. Worried that the episode might cause credit markets to stop functioning, the Fed stepped into the markets to buy corporate debt for the first time.

How can investors navigate turbulent markets and survive at a time when there is nowhere to hide? The first step is to adopt a “barbell” approach to portfolio construction. This means stocking up on assets considered to be of mild risk and a few “rock star” bets that can outperform a portfolio fully invested in low-risk assets, which are already priced for perfection due to central bank purchases. A static portfolio invested in cash and corporate bonds rated double B, or just below investment grade, has generated more excess return over U.S. Treasuries over the past five years than one fully invested in triple B bonds, given the same initial yield.

The second step is to hold more than enough cash, as much as a quarter or even a third of a portfolio. In fragile markets with scarce trading liquidity, cash gives investors an invaluable opportunity to buy assets in a fire sale, when everyone else is running for the exit.

The last step is to understand that active management can provide benefits. Many years of quantitative easing have created many “zombie” firms, or companies that would otherwise be out of business if not for central bank largesse. Going forward, certain business models may prove unsustainable, with the Covid-19 pandemic accelerating the reckoning. Already, distressed issuers in the global junk bond market have jumped to 8.3% of the total from 3% pre-pandemic, despite markets climbing back to their January highs. Understanding which sectors and firms are tomorrow’s winners and losers will be a key driver of performance going forward.

Perhaps the most important question is whether markets will ever come out of the rabbit hole. The answer is not likely as long as current policies remain in place. The U.S. elections in a few weeks will determine how the policy tide will turn. Tax cuts from the Treasury Department and asset purchases from the Fed during the current administration boosted stock prices and corporate profits but failed to improve productivity and wages. A sustainable recovery calls for broad-based support to the real economy, including individuals and small businesses.

An economic plan focused on the real economy and public services, like the one proposed by Democrats, may bring growth back to the states and minorities, which have been left behind. This may generate faster inflation, leaving Wall Street without a Fed “put” for all assets. Over time, however, it is more likely to make the economy and financial markets stronger.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Alberto Gallo is a portfolio manager at Algebris Investments, where he runs the Algebris Global Credit Opportunities fund.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.