(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It was the shot (of inflation) heard round the world. The Labor Department said this week that its consumer price index surged 6.2% in October from a year earlier. The increase was the biggest since 1990, when oil prices soared in the months before the start of the first Gulf War. This was surely proof that not only had “Team Transitory” lost the inflation debate but that the U.S. was on the verge of becoming the next Weimar Republic! Umm, let’s slow things down a bit.

This is not about playing down the ill effects of high inflation. Consumer prices that are suddenly rising at a much faster rate disproportionately hurts those at the lower end of the income and wealth spectrum — a group that has only grown since the financial crisis more than a decade ago — as well as the elderly, who are likely living off their savings. Inflation can also be bad for businesses, especially if it eats into profit margins and causes consumers to pare back their spending because of sticker shock.

The good news is that the message being sent by the financial markets is that all the hand-wringing over inflation may be a bit premature. It’s not as if this latest CPI report was an outlier; the gauge started popping higher with the March data and has been elevated since April. And yet the stock market as measured by the benchmark S&P 500 Index has risen about 13% since April 12, the day before the March CPI report was released. The State Street Investor Confidence Index for North America, which is derived from actual trades rather than survey responses, is the highest since early 2016. That makes sense when you consider that companies are thriving. Corporate profit margins have expanded to some of the widest on record, showing that customers are ready, willing and able to absorb the higher prices being asked.

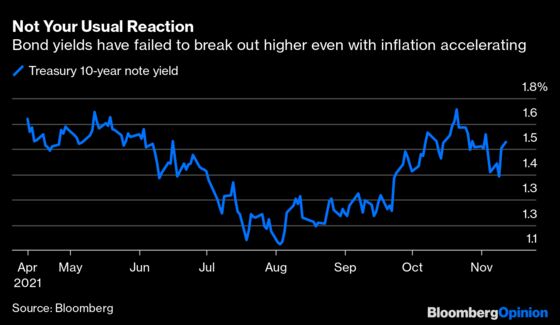

At 1.55%, the yield on the benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury note is actually down since April 12, falling from 1.67%. In 1990, yields — which help set rates for everything from mortgages to rates to corporate bonds — were above 8%. Of course, the Federal Reserve’s heavy involvement in the bond market goes a long way toward explaining why yields are so low. Even so, breakeven rates on five-year Treasuries, which are a measure of what traders expect the rate of inflation to be over the life of the securities, are only around 3.12%, which seems underwhelming given all the hyperventilating over the CPI report.

Foreign-exchange traders are also sanguine about the potential for high rates of inflation sticking around for longer than most anyone expected. Although the Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index has risen since April 12, as would be expected in a period of accelerating inflation, it’s up just 2.33% since then. Also, the benchmark is still below its average over the past five years.

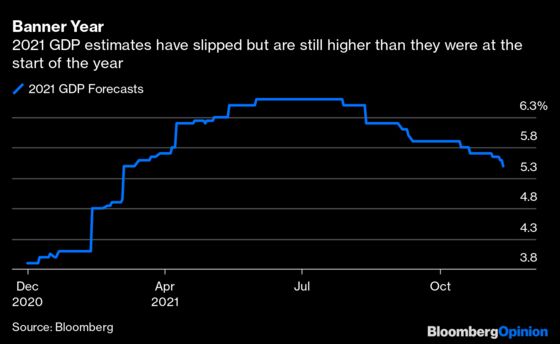

Economists have now had seven months to track and analyze the impact of higher inflation rates on the economy, and the result is a collective shrug. A monthly survey by Bloomberg News released Friday showed that economists don’t expect the next recession to start until 2025. Also, they don’t see much impact on the economy, which they forecast will expand at a very healthy 4.8% rate this quarter, down just one tenth of a percentage point from the October survey. The forecast for the first quarter of 2022 was bumped higher to 4.3% from 4%.

As for inflation, they expect the CPI to rise 3.6% next year. Although that is elevated for an economy that has become used to annual gains of around 2% or a little below in recent years, it’s down from the 4.5% expected for 2021 and nowhere near the rate needed to cause real economic damage.

It’s fair to dismiss such groupthink among economists given how wrong they have been forecasting since the start of the pandemic. But what’s harder to dismiss is historical context. Households are in perhaps their best shape financially in history. Their collective net worth as measured by the Fed rose by $23.2 trillion in the four quarters ended June 30 to $141.7 trillion. The all-time high for any one calendar year was $11.6 trillion in 2019.

Americans have also built up $2.7 trillion of excess savings since the start of the pandemic, according to Bloomberg Economics, about triple what it is normally. Tom Porcelli, the chief U.S. economist for RBC Capital Markets, calculated in a recent report that wages for the year are already about $400 billion higher than they would have been had the pandemic never happened, using a pre-pandemic baseline estimate. What that means is come the end of December, consumers could be sitting on almost an extra year of income gains.

Sure, financial markets could be too complacent about faster inflation. It wouldn’t be the first time the collective wisdom of investors underestimated some risk. But it’s hard to argue that households don’t have the financial wherewithal to absorb these higher prices for months to come. One test may come Tuesday when the Commerce Department releases its retail sales report for October. Economist don’t foresee a buyer’s strike, estimating a very healthy 1.1% gain, or more than three times the monthly average in the five years before the onset of the pandemic.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is the executive editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.