(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s hard to beat the unscripted theater of the Champions League, which pits Europe’s best soccer clubs and players against each other in a battle for sporting immortality and unimaginable riches. And, in fairness to the superstars, it’s been a particularly stirring tournament this year, with Liverpool and Tottenham Hotspur both coming back from the dead against Barcelona and Ajax to claim their places in the final.

Right now, though, there’s some equally arresting drama happening off the field. Manchester City, one of the world’s richest clubs and the recently crowned English champions, faces a potential ban from the elite European competition. Owned by Abu Dhabi’s Sheikh Mansour, the talent-packed team could be barred for one season if the adjudicatory chamber of governing body UEFA decides it breached financial rules designed to curtail excessive spending on players.

Last year, Der Spiegel published emails revealing allegedly inflated sponsorship deals that concealed where some of the club’s money was really coming from. UEFA investigators’ decision to refer the Manchester City probe for judgment suggests there is a compelling case to answer.

Should the adjudicators find against the club, rival teams and fans will be enraged by anything less than a ban. After all, why bother complying with these so-called Financial Fair Play rules (known to everyone in the game as FFP) if there’s no ultimate sanction? The Italian club Roma, for example, claims it sold top player Mohamed Salah to Liverpool because it wouldn’t have been compliant otherwise.

UEFA’s credibility would be shattered if it just gave Manchester City another financial slap on the wrist, as has happened in the past. Der Spiegel’s reporting showed how supine the governing body was when questions about Manchester City’s and Qatari-owned Paris Saint-German’s compliance arose previously.

Manchester City says the accusations of financial irregularities are “entirely false” and its accounts “are full and complete and a matter of legal and regulatory record.” It is unlikely to back down without a protracted fight.

While it won’t find much sympathy if it loses that battle (it seems a reasonable principle that competing teams should all follow the same rule book), there is another question here: Does FFP even work for the greater good of the game? I’d argue not. It has tended to enshrine the power of already dominant teams by hobbling the capacity of up-and-comers to spend their way to the top table. In future, it might be “fairer” to weaken or scrap the break-even requirement – which allows clubs to spend only what they make in revenue – and let club owners invest how they please.

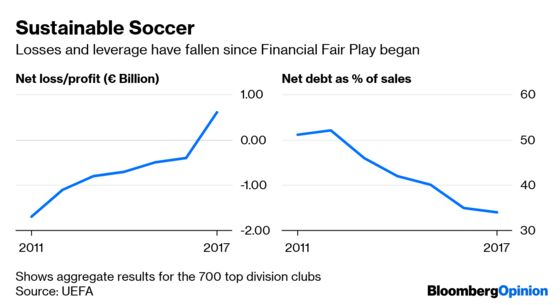

FFP was dreamt up after arriviste billionaire owners like Chelsea’s Roman Abramovich and Sheikh Mansour sparked an arms race for players. As salaries and transfer fees ballooned, a swathe of clubs made losses in the effort to keep up. Eight years since the system’s introduction, UEFA claims it has been a success and – superficially at least – the data seem to back that up. In the 2017 financial year, the 700 top division clubs in Europe made an aggregate profit for the first time and their balance sheets are in much better shape.

Financial rewards haven’t been shared around, though. The top dozen clubs have added 1.6 billion euros ($1.8 billion) of sponsorship and commercial revenue over the past decade, while the next 700 have added less than 1 billion euros between them, UEFA data show. Europe’s 30 leading clubs had combined revenues of almost 10 billion euros in fiscal 2017, half of all the sales generated by the continent’s top division teams.

Because of FFP, the clubs that bring in most revenue can spend most on players and wages, meaning they’ve a much better chance of qualifying again and again for the Champions League, whose 32 participants shared 2 billion euros of proceeds between them last season. In contrast, the fair play rules have made it harder for the large cohort below to catch up because a new owner can’t just inject a wad of cash – as Abramovich and Sheikh Mansour did back in the day. In effect, the big guns used FFP to pull the ladder up.

The English Premier League is still reasonably competitive (although Manchester City appears to be challenging that notion after winning it twice in a row), thanks in part to a collectively negotiated TV deal. But elsewhere national football has become horribly predictable, as this list of recent winners shows.

In short, instead of making football more equitable, FFP has helped make it more polarized and reinforced the power of already wealthy clubs. The system “kills competition and that’s bad for the game,” says Stefan Szymanski, a sports finance expert at the University of Michigan. As American sports fans – with their player drafts, wage caps and rich-team surcharges – understand, a lack of true rivalry is a very dull thing.

UEFA is thinking about reforming FPP and there’s no shortage of things it could do. Budget limits or U.S.-style salary caps sound appealing, but these types of intervention would invite a breakaway by the elite clubs. They are already angling to change the format of the Champions League to ensure most of them qualify automatically, thus limiting the number of qualification places to just a handful.

Another approach might be to give clubs that finish lower down a domestic league a greater share of the prize money or television receipts than the winners. However, in the U.S. similar rewards for failure have encouraged teams to deliberately lose games, in their cases to get better draft picks.

In truth, the ultra-capitalist approach of European soccer owners doesn’t really marry well with the surprisingly socialist tools used by the Americans to maintain an even playing field. So maybe it’s just better to let it rip. Softening or even getting rid of FFP altogether might be the easiest way to make things more competitive.

Would some clubs get into financial difficulties again? Almost certainly. It’s largely unheard of, though, for a leading club to go bankrupt and disappear altogether. There’s always somebody else willing to put in more cash, says Szymanski. For example, Italian club Parma went bankrupt in 2015, got relegated to the fourth division, then quickly fought its way back to the top again.

There’s no question that money already has too much influence over soccer, explaining the soulless atmosphere at many English top division games as clubs raise ticket prices and chase merchandise-loving global fans. But you can’t wind back the clock, and die-hard supporters can at least take comfort in the travails of maybe the world’s best-known soccer “super-brand:” Manchester United.

While that famous club is one of of the three biggest revenue generators in soccer, according to Deloitte, it finished a distant sixth in the England’s top division this season and failed to get past the quarter-finals of the European Champions League. PSG, Manchester City and Juventus, also failed to reach the competition’s semi-final, the latter despite signing mega-star Cristiano Ronaldo for 100 million euros. This year’s finalists, Tottenham and Liverpool, are paragons of modesty by comparison (although you’d hardly describe them as poor).

Throwing money at a soccer club still won’t buy you guaranteed success. Billionaires should be free to try though.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.