(Bloomberg Opinion) -- A high-end luxury Lucid Air electric sedan comes replete with a glass roof and more than 500 miles of driving range. With zero tailpipe emissions and oodles of interior space, it’s quite the $169,000 package.

Even though the California start-up behind the Air won’t start customer deliveries until later this year, its many admirers are betting it can mount a serious challenge to Tesla Inc. and Germany’s luxury automakers.

It’s not just the cars that come with a big price tag. The company, to be known as Lucid Group Inc., could be valued at around $37 billion once it begins trading on Nasdaq next week after its merger with Michael Klein’s special purpose acquisition company Churchill Capital Corp. IV. Shareholders approved the transaction on Friday after a 24-hour delay to gather sufficient votes. That would mean Lucid is worth around two-thirds the market value of Ford Motor Co., which sells more than 5 million vehicles in a normal year. Fisker Inc., another pre-revenue electric vehicle start-up, is worth “just” $4.8 billion.

Lucid has channeled all of the excitement around a post-combustion-engine world first championed by Elon Musk, who’s leadership of Tesla Inc. helped make him the world’s second-richest person. Even before Lucid starts generating revenue, it’s also shaping up to be quite the wealth-creation machine for company and SPAC insiders.

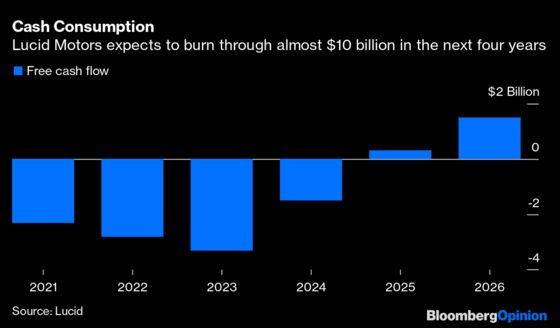

Though it boasts some impressive technology and experienced managers, Lucid still has a great deal to prove. As of last month, it had reservations for barely 10,000 vehicles worth around $900 million in revenue. This is dwarfed by the almost $10 billion in cash the company expects to burn through in the next four years, in part because it’s ambitiously decided to build vehicles itself at a plant in Arizona. As Musk would attest, making cars is hard and very capital intensive.

Like Tesla, Lucid has a huge following among amateur investors, many attracted through online platforms like Reddit. Some have already had their fingers burned speculating with Churchill stock. I’d caution them against getting too carried away once Lucid’s gets its own stock market ticker — LCID.

In financial terms, Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund is the clear winner so far, thanks to a more than $1 billion investment announced in 2018. The Public Investment Fund will have a more than 60% stake in Lucid valued at around $23 billion. Not bad for a country whose wealth stems from the oil products electric vehicles will gradually displace.

There are almost $170 million in “transaction expenses,” implying large fees for various financial institutions who worked on the deal. That’s practically a rounding error compared to Churchill, the SPAC sponsor led by Klein, a former Citigroup Inc. investment banker. It paid a little more than $40 million for shares and warrants that are now worth around $1.6 billion. Some are subject to performance hurdles and none can be sold for 18 months. They’ll likely be shared between Klein’s firm, M Klein & Co., other financial partners and a Churchill “brain trust” that includes former Apple design boss Jony Ive and former Ford CEO Alan Mulally. Churchill declined to comment.

After exercising existing stock options, Lucid boss Peter Rawlinson will own 12.9 million shares valued at around $300 million. The former Tesla engineer could yet make a great deal more: An executive share plan will provide him with restricted stock that the prospectus conservatively values at $556 million. They’re subject to time- and performance-based criteria that he’s well on the way to meeting. He’ll get the whole amount if he remains in the job for four years and Lucid’s market value doubles. Lucid declined to comment

Though much of this wealth exists only on paper for the moment, it explains why seemingly everyone in the world of business and finance wants their own SPAC. There have been fewer initial public offerings of blank-check firms lately due to heightened scrutiny from regulators and some high profile flops. But the hundreds that have gone public already are on the hunt for mergers, often targeting electric-vehicle companies, in part because retail investors go giddy for them. The Lucid deal is the poster child for the riches they hope to make.

The SPAC transaction provides Lucid with $4.4 billion, a sum it’s likely to burn through in a couple of years. The company doesn’t expect positive cash flows before 2025 and the prospectus notes it will need to raise additional funds through equity or debt.

Capital isn’t the only potential constraint. Germany’s automakers have woken up to the potential threat posed by upstarts like Lucid and have unveiled impressive luxury electric models such as the Mercedes-Benz EQS, Porsche Taycan and Audi e-tron GT. This week Mercedes-Benz vowed to spend more than 40 billion euros ($47 billion) this decade to electrify its lineup.

For now Lucid is entirely focused on the relatively small market for luxury sedans. Its second electric model, a sports utility vehicle, won’t arrive until the end of 2023.

Churchill’s shares soared as high as $65 back in February amid a speculative fervor that’s partly receded — they now fetch barely one-third as much. If maintained, that $37 billion valuation will allow Lucid to issue more stock cheaply, if required. But at these levels it’s vulnerable to a further pullback if there are manufacturing hiccups or other disappointments. Above all Lucid needs to show it can turn paper wealth into hard cash.

Thevaluation is based on 1.6 billion shares outstanding after the merger.

The five market value hurdles are: $23.5 billion, $35.25 billion, $47 billion, $58.75 billion and $70.5 billion. They're assessed according to the average market capitalization over any six-month period and will be forfeited if not achieved in five years.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.