Lower London Rents Are a Bad Omen for House Prices

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The traditionally buoyant London rental market has taken a hit — with the damage most readily apparent at the top. And the consequences for the city’s renters, landlords and home owners will be felt for quite some time yet.

One key factor behind the ailing rental market is the exodus of people leaving London — especially the highly paid and economically mobile — due to both the pandemic and Brexit. The Office for National Statistics estimates that, in the summer of 2020, 893,000 non-U.K. residents left the country. The government-funded Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence reckons the outflow was even higher, at 1.3 million, with more than half departing from London. That’s equivalent to around one in 12 leaving the city.

This has led to fewer tenants and a drop in rents. For people renting, that means more choices for housing and more room to negotiate on pricing. But there is little sign that cheaper rentals are attracting more people into the city. Many are still working from home, and a dearth of job opportunities for new grads means there’s little hope of the usual summer influx of new residents.

So landlords aren’t faring well. Skinny rental yields, across price points, have long been a feature in London — they’re lower here than in any other part of the country. (Rents in the capital may be high relative to earnings, but compared to the cost of the real estate you are occupying as a tenant, renting has been more attractive than buying for years.) Rental properties have often been held as more of a trophy asset, with owners comforted by the perception of liquidity and endless international demand pushing up the value of the real-estate. Now this illusion is faltering.

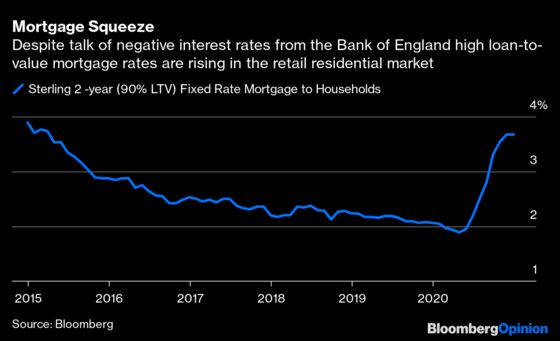

Zoopla data show that demand from private landlords to buy rental properties has dropped by over a half from five years ago. This has been exacerbated by a 3% higher stamp duty for second homes from April 2016 and sharply rising mortgage rates for high loan-to-value properties — effects that are felt most acutely in prime areas such as central London.

That’s why we’re seeing the most pronounced drops in rent in the highest price inner city boroughs of Kensington and Chelsea, Westminster and Islington. Meanwhile, the outer suburbs have been cushioned by a noticeable pandemic shift to bigger, more rural properties, driving up house prices elsewhere in the U.K. (Rents outside of London are little changed.)

Just as rents have fallen, property costs and taxes have been rising. Many owners are only now appreciating the impact as they complete their 2019/2020 tax returns for the Jan. 31 deadline. They are discovering just how much the scaling back of benefits, such as the deductibility of mortgage interest costs, is taking out of their bottom lines. And the extended government ban on tenant evictions during the pandemic is also eating into rental income, as now around 7% of renters are in arrears.

In short, being a landlord in London is not the attractive proposition it once was. Yet renting a slightly cheaper swanky apartment in a glamorous district still seems to be as out of reach as ever for most. The market will have to self-correct.

For now, the impact on property prices has been disguised by the stamp duty holiday, which has created an artificial rush to buy homes. However, with the prospect of future increases in capital gains taxes adding to rising costs, we’re likely to see more landlords sell their properties. They’ll have a hard time forgetting those losses from tenants unable to pay rent during the crisis. And more flexible approaches to work will probably keep demand to rent in the capital well below pre-pandemic levels. This means it could eventually get harder to rent.

So, instead of declining rents heralding a swift return of residents to London, they are most likely a portent of what is to come for the city’s property prices. Although there is some hope for renewed overseas demand — the Home Office expects over half a million Hong Kongers to potentially relocate over the next few years, with many coming to the capital — this will be gradual.

Never has it been clearer that London will always be a global city: It needs foreigners to thrive and survive, and that goes for property prices too.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Marcus Ashworth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European markets. He spent three decades in the banking industry, most recently as chief markets strategist at Haitong Securities in London.

Stuart Trow is a credit strategist at the European Bank for Reconstruction & Development. He is also a pensions blogger, radio show host and member of numerous retirement, finance and audit committees.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.