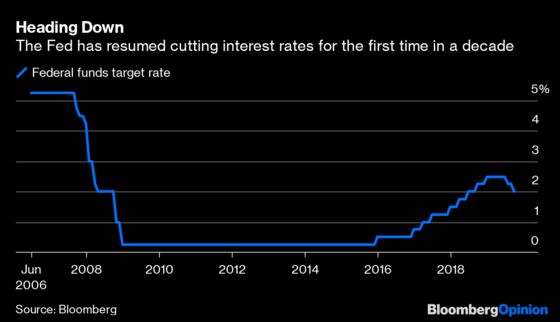

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Odds have swung heavily in favor that the Federal Reserve will cut interest rates again at the end of this month even with Friday’s news that the U.S. unemployment rate dropped to a 50-year low of 3.5% last month. Central bankers are focused on the risks to future outcomes and will tend to pay less attention to lagging indicators such as the unemployment rate as they consider their next move. Thinking more broadly, the data overall is not showing enough strength to justify a holding rates steady.

In the wake of the September Federal Open Market Committee meeting where policy makers reduced their target rate for overnight loans for the second time since July, I believed that, assuming the data held up, the Fed would be on hold with the odds tilted toward a rate cut. The data, however, has been less resilient than hoped and as it stands now pushes the Fed in the direction of a rate cut.

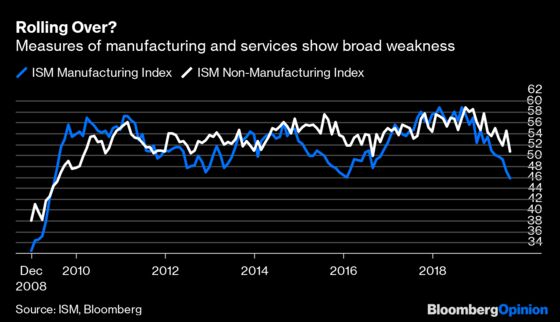

The Institute for Supply Management’s report last week showing manufacturing activity in September fell to a 10-year low set the tone by revealing that factories are under substantial pressure from weakening global economic growth. The part of the index measuring new export orders has fallen to levels associated with past recessions. And we all know that in addition to the challenge of slower global growth, firms are also struggling to cope with the trade war, a saga with no end in sight.

Manufacturing, of course, is a small part of the economy relative to services. But last week showed that the service sector is also buckling. The ISM’s non-manufacturing index also revealed widespread weakness. New orders fell to 53.7 from 60.3, still in expansion territory but closing in on the 50 mark that is the dividing line between expansion and contraction.

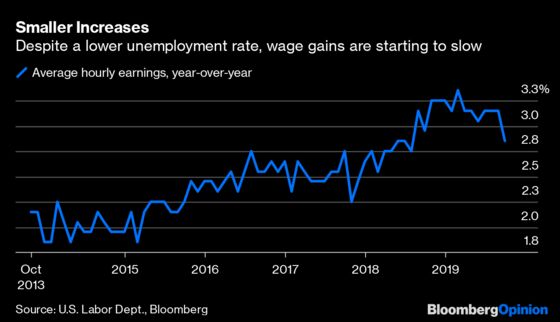

The employment report further substantiated concern that the economy did not regain its momentum as the third quarter drew to a close. While job growth remains solid at a monthly pace of 157,000 over the past three months, it has decelerated from a three-month pace of 245,000 at the beginning of the year. The Fed would likely be happy with such a number absent the downside risks to the outlook. Those risks, however, suggest substantial possibility that job growth will decelerate further in the months ahead.

The drop in the unemployment rate to 3.5% will raise some eyebrows at the Fed. The more hawkish policy participants will worry that they risk overheating the economy with lower rates. But it is hard to make that argument when wage growth remains tepid, with average hourly earnings rising 2.9% in September from a year earlier, the smallest increase since July 2018. Also, inflation is still bouncing along below the Fed’s 2% target.

In fact, the drop in the unemployment rate gives increased weight to the very low estimates of the natural rate of unemployment. Fed Vice Chairman Richard Clarida recently said that he believes estimates of sustainable unemployment below 4% are plausible. In such a world, 3.5% unemployment does not prevent an additional rate cut given fading economic momentum. Moreover, the unemployment rate is a lagging indicator; the fact that it is falling does not necessarily imply all is well with the economy.

In may seem odd that the Fed will cut rates a third time when the economy is, as Fed Chairman Jerome Powell and others describes it, “in a good place.” The core voting members on the FOMC, however, seem inclined to cut rates until they are confident they have offset the negative forces weighing on the economy.

Isn’t the 50 basis points of rate reductions that have already been implemented enough to keep the expansion alive? Maybe, but given the proximity to the lower bound, persistently low inflation, and a desire to continue reaping the benefits of low unemployment, the Fed will error on the side of another rate cut. Steady data to improving data would be necessary to stop that cut. As of the first week of October though, the data flow is steady to worsening, holding the odds of a cut very high.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Burgess at bburgess@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Tim Duy is a professor of practice and senior director of the Oregon Economic Forum at the University of Oregon and the author of Tim Duy's Fed Watch.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.