He should know. Tesla Inc. had a devil of a time getting the Model 3 out of the tent, and there’s a long list of artfully teased products ranging from the Tesla Semi to the recently canned “Plaid+” that are notable chiefly for what might be called their extremely limited-edition status.

Lordstown Motors Corp. is experiencing this truth acutely. The electric-truck startup just issued a going-concern notice, less than eight months after listing via a special purpose acquisition company, or SPAC. The Endurance, Lordstown’s flagship model-to-be, must be developed, approved by regulators, produced at scale and then sold if the company is to actually endure. And the company doesn’t believe the almost $600 million it had on hand at the end of March will get it there.

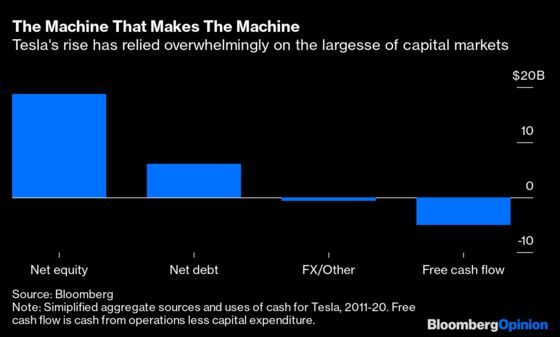

They may be on to something. Consider the company every electric vehicle maker or wannabe-maker aspires to emulate, in stock-price terms at least: Tesla. That company is now almost 18 years old and just racked up its first year of selling half a million vehicles. Here is more or less how it got there, in financial terms; its sources and uses of cash over the past decade:

None of this is especially weird. Just being an automaker is capital-intensive enough. Building one from scratch that attempts to shift the underlying technology is, in financial terms, madness.

Even now, while Tesla has begun to generate free cash flow — almost $4 billion over the past four quarters — the amount is small relative to its valuation and ambitions, and relies heavily on sales of regulatory credits (with some Bitcoin gains thrown in). Despite claims of being self-funding or self-funding-adjacent, Tesla still capitalized on last year’s mega-rally in the stock to issue more than $12 billion of new equity — half of all the outside capital it raised, net, over the past decade.

Tesla was blazing a trail in electric vehicles and targeted passenger vehicles, the biggest segment of the autos market. It’s one where well-heeled first-adopters are willing to pay six figures for something cool but unproven. Lordstown is following and has set its sights on commercial fleet pickups.

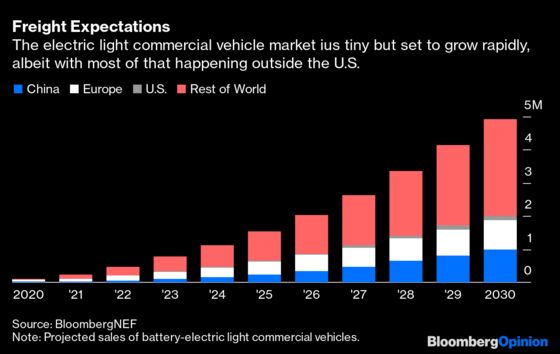

That is a smaller market, with about 10 million light-duty vehicles sold worldwide in 2019, versus 84 million passenger vehicles. In BloombergNEF’s latest outlook, released Wednesday, it foresees demand for fully electric light commercial vehicles rising almost 50-fold by 2030. However, the U.S. is a relative laggard compared to China and Europe.

This market is also fiercely competitive. Ford Motor Co., especially, is one to watch, with an electric version of its dominant F-150 truck due on the road early next year and a new hybrid compact truck priced at less than $20,000, the Maverick, unveiled this week.

Meanwhile, Lordstown is trying to differentiate itself by using hub-motors in each wheel. This is aimed at reducing parts and improving performance, but the technology is untested at scale, raising Lordstown’s own development risks and potentially putting off fleet buyers prizing reliability over innovation.

The only way Lordstown could even attempt this is with extraordinarily patient capital. Recreating that Tesla cash-flow chart for Lordstown, it would consist mostly of a big bar labeled “We got SPAC’d.”

Venture funds used to fund this sort of thing; Tesla was eight years old when it went public, compared with Lordstown’s ripe old age of two. Tesla’s own meteoric rise, amid a wider surge in green stocks, enabled the SPAC wave. Some $7.5 billion has been raised for electric vehicle-related companies via SPACs, according to Bloomberg NEF, and there’s another $11.8 billion being targeted (of which luxury car brand Lucid Motors Inc. accounts for more than a third).

Yet Tesla’s own history shows electrifying transportation depends heavily on cheap capital, government support or having a svengali like Musk running things. As incumbents such as Ford weigh in, they’re backed by the profits of their traditional vehicle sales.

This isn’t to say electrification is doomed once Treasury yields get back above (horrors) 2%. Despite the collapse in its stock price, even Lordstown isn’t necessarily done yet. There’s still roughly $10 billion of Advanced Technology Vehicle Manufacturing loan capacity at the Department of Energy, for one thing.

Still, Warren Buffett once mused that the smart investor a century ago would have “gone short horses” rather than try to pick the winners among thousands of then-new carmakers, most of which disappeared. Today’s SPAC-fueled race will by definition create unicorns that exist on a diet of third-party capital and will starve when that’s taken away.

Comment on the 1Q 2021 earnings call, though variations on this theme are a fairly consistent lament from Musk.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.