What China’s $30 Trillion Credit Pile Doesn’t Tell You

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Investors are at it again, sorting through the heap of China’s credit data.

Last month’s aggregate social-financing numbers, released Sunday, show the flow of new credit in (and around) the financial system fell 41 percent in February from a year earlier. Retail loans posted their largest monthly drop on record. Companies continued to struggle with working-capital financing; bonds were the main channel of funding.

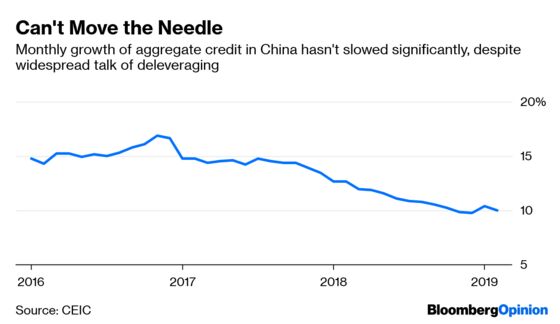

Looking for signals of economic recovery in such noisy data is a fool’s errand. Just a month earlier, the same figure surged 51 percent. The total stock of debt across the system remains 205.6 trillion yuan ($30.6 trillion) and is still growing at 10 percent, just below the average in previous years.

China has been through three credit easing cycles in recent memory: 2008 to 2009; 2011 to 2013; and 2014 to 2016. Each additional yuan of credit has become less effective as the debt pile grows bigger. Leverage pushes asset prices higher than they would be otherwise, meaning the drop is inevitably sharper, too. Dislocations rise and the hit to the real economy is severe.

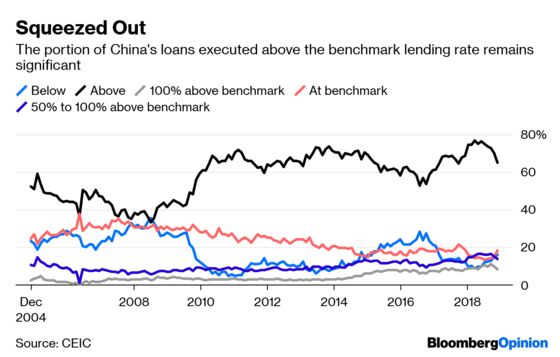

To address this, Beijing has been trying to deleverage its financial system over the past 18 months. The result has been a liquidity squeeze, which has choked off financing to companies that need it. Talk of disinflation is emerging. Defaults are rising.

Beijing’s recent stimulus plans have taken various shapes. This could imply that China is nearing the fourth round of a credit surge. When January data showed aggregate financing rose sharply, after two slightly slower months, analysts started whispering that the taps were opening up again.

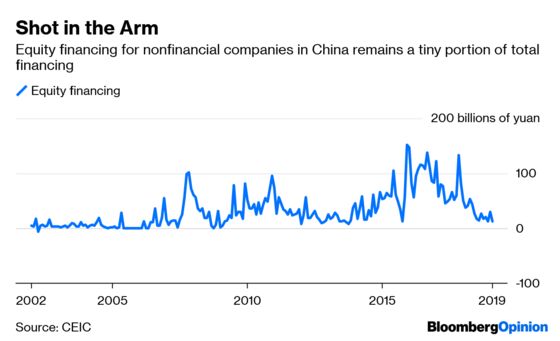

All told, it’s looking a lot more like the later stages of a typical credit cycle than the beginning of one. Private companies still aren’t benefiting from Beijing’s largess and account for just a tiny portion of bond issuance. Multiple efforts to encourage banks to start lending, including five reserve-ratio cuts over the past year, haven't moved the needle. Promised boosts to infrastructure spending, which have targeted railways and urban transit, are unlikely to stir much demand and activity. Two trillion yuan of tax cuts aren’t expected to give companies much relief, either.

Sure, an artificial and short-term lift may be within reach – with a few fiscal tricks, my colleague Shuli Ren has written. But until private companies’ confidence and balance sheets show signs of improvement, we won’t see any real upsurge in this cycle.

Officials continue to talk up their efforts to lend to small and medium enterprises. Nomura Research’s gauge of credit impulse – the change in new credit as a portion of GDP – has risen by just around 2.5 percentage points so far, with the economy far more leveraged. In previous up-cycles, it rose 30.2 percentage points (2009), 18.7 percentage points (2012), and 13.9 percentage points (2014).

Ultimately, pumping more credit into the financial system won’t help if the pipes are clogged. That’s why interest-rate cuts and other policy instruments aren’t flowing through, as we’ve explained here. In the current state of economic anxiety, what the system really needs is a big dose of equity financing to cushion the stresses, especially as bad debt write-offs have started to surge. Till then, hunting for clues in Chinese credit may lead nowhere.

For example, this measure accounted for 0.8 percent of GDP in February, almost half the amount in previous years. Buton a year-to-date basis, growth was on par with years past.

Broadly, the expansion and contraction of borrowers' access to credit over time

To further complicate matters, the difference between the balance sheets of state-owned companies and private firms has led to two credit cyclesin China.

Nomura defines and calculates this as the 12-month change in the ratio of the 12-month change in outstanding aggregate financing to the four-quarter rolling sum of nominal GDP. It says this is a more distinct leading indicator of the economic cycle.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Anjani Trivedi is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies in Asia. She previously worked for the Wall Street Journal.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.