Libor Should Die With a Whimper, Not a Bang

The deadline for finance to stop using Libor is fast approaching and almost everyone is cutting it close, writes Mark Gilbert.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The deadline for the finance industry to stop using Libor is fast approaching, but markets remain wedded to the discredited and soon-to-be discontinued suite of interest rates. Regulators may need to become fiercer in overcoming the institutional apathy toward new benchmarks, or risk troublesome market dislocations.

By the end of the year, banks are supposed to cease writing new financial business that uses the London interbank offered rate as the basis for calculating borrowing costs across different currencies and maturities. But there’s a massive legacy of contracts outstanding still attached to the rates; the U.S. Federal Reserve estimates that $223 trillion of financial products are tied to dollar Libor alone.

The demise of Libor became inevitable because of two issues — one practical, one reputational. First, as the wholesale funding market between banks evaporated in the wake of the global financial crisis, it starved the system of the underlying transactions needed to judge what the cost of money should be. Mark-to-market became mark-to-made-up.

Second, lawsuit after lawsuit has found that the traders that supplied the reference rates were rigging their submissions to enhance their profits. Banks have paid more than $9 billion in fines for lying about Libor.

Regulators in different jurisdictions have recommended alternative so-called risk-free reference rates , including the Sterling Overnight Interbank Average rate in the U.K. and the Secured Overnight Financing Rate in the U.S. But Libor interest rates are still deeply embedded in the fabric of finance.

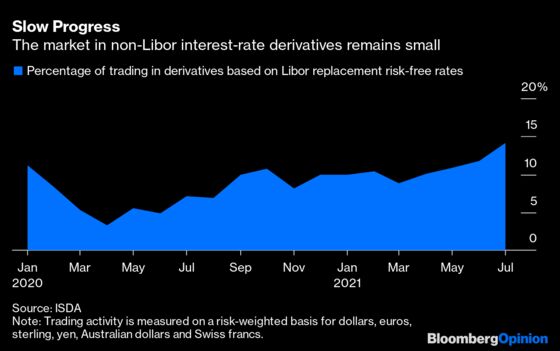

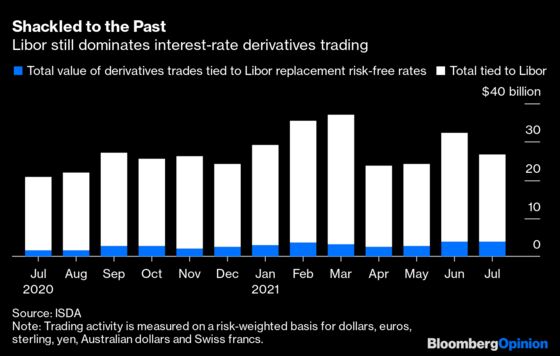

In the global interest-rate derivatives market, contracts tied to Libor still account for more than 85% of all trades, according to figures compiled by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association. While the percentage based on other benchmarks has increased in recent months, progress remains slow.

Libor is by far and away the dominant reference rate. On a risk-weighted basis, the old benchmark accounted for almost $23 billion of the $26.6 billion of derivatives traded last month. On a notional basis, just 12% of July’s $127 trillion of interest-rate derivatives trading was associated with the replacement rates.

It’s not just the derivatives market that’s dragging its feet. Libor is intertwined throughout the commercial system and still sets the borrowing costs for a swathe of products, including corporate loans, that are stuck using the old benchmarks.

Chatham Financial, a Pennsylvania-based consultancy firm, recently surveyed 100 corporate treasurers overseeing annual revenue of $1 billion to $25 billion. It found that 39% were “completely unsure” if they needed to take action in preparation for the end of Libor.

Earlier this week, U.S. regulators including the Treasury, the Federal Reserve and the Securities and Exchange Commission said they’re concerned that nonfinancial companies aren’t being offered alternatives to Libor in commercial transactions. “The transition is at a critical juncture,” they wrote in a joint letter to the Association for Financial Professionals and the National Association of Corporate Treasurers. “We have stressed the importance of reference rates built on deep, liquid markets that are not susceptible to manipulation.”

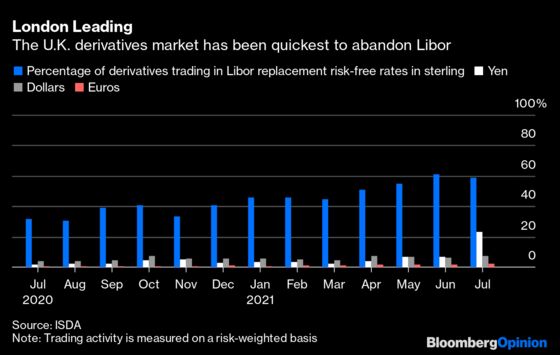

Geographically, one market is further ahead than its peers. In the U.K., non-Libor derivatives trades surpassed those tied to the old benchmark in April for the first time. And last month, almost 60% of trading in the sterling market was in contracts tied to alternative benchmarks. That still leaves a lot of activity tied to sterling Libor with less than five months to go until it’s supposed to die. But it’s progress.

As the guardians of Libor’s home market, U.K. regulators have been leading the charge to abandon the tarnished benchmark, and those numbers suggest they’ve been more successful than their counterparts elsewhere by adopting a more threatening stance. In March, for example, the Financial Conduct Authority and the Bank of England suggested that progress on moving to new reference rates should be “part of the performance criteria” for determining bankers’ bonuses.

Inertia has proved to be a powerful disincentive to shifting away from the existing benchmark alignments. But the risk of contracts unraveling, hedges failing or interest-rate mismatches fracturing commercial arrangements increases as Libor’s endgame gets closer. Market overseers should consider a sterner approach to ensure that Libor expires with a whimper, not a bang.

Bloomberg Index Services Limited, an affiliate of BloombergL.P., the parent of Bloomberg Opinion, is the official vendor calculating spread adjustment and other fallback calculations on behalf of ISDA. It also calculates the Bloomberg Short-Term Bank Yield Index, an alternative to SOFR.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Gilbert is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering asset management. He previously was the London bureau chief for Bloomberg News. He is also the author of "Complicit: How Greed and Collusion Made the Credit Crisis Unstoppable."

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.