Wall Street Bankers Will Have to Work a Little Harder

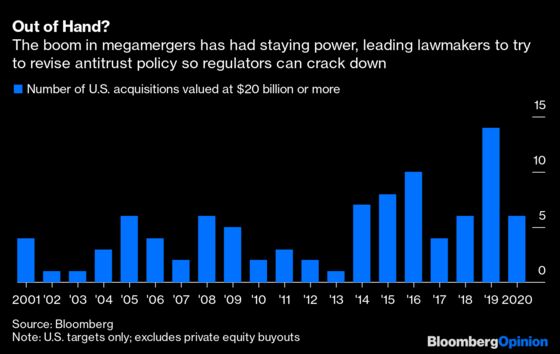

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The list of corporate megamergers permitted by U.S. regulators over the last decade is a jaw-dropping study in the failure of the country’s antitrust laws. It’s against this backdrop that Senator Amy Klobuchar’s proposal to overhaul competition policy is not only sensible, but urgent.

Klobuchar, a Minnesota Democrat who will lead the Senate’s competition panel, plans to introduce legislation that would give antitrust enforcers at the Federal Trade Commission and Justice Department greater power and resources to block potentially harmful mergers. Her proposal directly targets the biggest shortcomings of today’s laws and, importantly, would shift the burden of proof from the regulatory bodies to the companies. Because of the costs and time associated with that added burden, chief executives might be discouraged from even attempting the most visibly problematic deals.

Those who went ahead with a deal would face other significant hurdles. The Clayton Act of 1914 forbids transactions that demonstrably produce a reasonable probability of reducing competition, which essentially requires regulators to present a crystal ball at every case. Klobuchar would rewrite the rules to instead prevent any mergers that “create an appreciable risk of materially lessening competition,” where the mere risk of harm is enough and where “materially” is defined as “more than a de minimis” or trivial amount. Regulators also wouldn’t have to first define the market as they do now — a process that can trip them up in today’s world because the lines between industries have so blurred. Some businesses straddle a few.

The underlying motivation of most acquisitions is to gain some degree of pricing power, so you may be left thinking, will any deals get done then? Of course the answer is yes, but the stringency of Klobuchar’s bill may also be a political vulnerability. Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase & Co., and other investment bankers won’t take kindly to Democrats trying to quash their lucrative M&A matchmaking business.

Over the last decade, the top three advisers including JPMorgan helped complete more than $5 trillion of M&A — each. In fact, there have been so many big mergers in a relatively short time that it would seem as if some industries have run out of deal options. And so as investment bankers continue to hint at large backlogs, speculators are having to contemplate increasingly bizarre permutations. One analyst even recently posited that JPMorgan itself might buy Target Corp., one of the world’s biggest retailers.

The chief targets of the Democrats’ bill seem to be technology giants — such as Amazon.com Inc., Facebook Inc. and Alphabet Inc.’s Google that have come under scrutiny by Congress for abusing their power — as well as the most egregious cases of market concentration in other industries. Consider T-Mobile US Inc.’s takeover last year of Sprint Corp. It not only removed a key low-cost competitor and reduced the national wireless market to just three players (a concern overridden by the perception that the deal would advance America’s 5G interests). The deal’s smooth regulatory passage also set a troubling precedent allowing mergers between direct rivals in already highly concentrated markets.

Klobuchar’s rules would make the process of scrutinizing so-called vertical mergers more straightforward. A vertical merger is when the acquirer and target operate in different parts of the supply chain or different industries entirely. AT&T Inc.’s $109 billion takeover of HBO parent Time Warner Inc. in 2018 is one such example. The federal judge who allowed that deal to proceed felt that the Department of Justice’s case against it relied too much on speculation of consumer harm and not enough evidence that the outcome would in fact be harmful. Only now are we beginning to see the proof, as AT&T presses its advantage as a giant of the wireless industry to push its HBO Max streaming-video service — for example, by not having HBO Max usage count against AT&T customers’ data caps the way watching Netflix and Disney+ would.

Not having to define the market may make it easier for regulators to police the tech landscape, where a handful of companies wield immense power over the ill-defined “personal data” space while hiding behind other more forgiving market labels, such as advertising. Klobuchar’s plan also calls for civil fines for monopoly behavior, whereas recommendations made by the House antitrust panel led by Representative David Cicilline of Rhode Island go further in seeking to potentially break up dominant tech companies. That could make Klobuchar’s legislation more palatable to Republicans. What’s missing from both proposals is the need to modernize U.S. antitrust laws by outlining rules specifically governing how consumer data can be used, requirements for its safekeeping and how violations would be handled.

As for M&A broadly though, Klobuchar’s prescriptions look to be right on target.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Tara Lachapelle is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the business of entertainment and telecommunications, as well as broader deals. She previously wrote an M&A column for Bloomberg News.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.