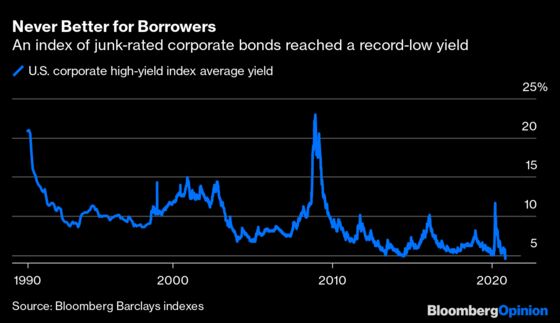

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The junk bond market’s magic number is 4.56.

First, the average yield for the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. corporate high-yield index plunged the most in seven months to 4.56% on Nov. 9, easily breaking the previous all-time low of 4.83% set in June 2014. Then, data compiled by Refinitiv Lipper found that investors poured $4.56 billion into U.S. high-yield bond funds in the week ended Nov. 11, the seventh largest inflow ever and the largest since June. It’s a strange coincidence, no doubt, though both figures would seemingly indicate that traders are getting increasingly comfortable with owning debt from some of the riskiest companies, even as Covid-19 outbreaks and hospitalizations escalate across America and the globe.

I’m skeptical of this latest junk-bond rally, and not just because yields have bounced back up from the record lows set on a day of unbridled Covid-19 vaccine optimism. The all-in 4.56% yield on a $1.52 trillion index comprising more than 2,000 separate bonds of various credit quality is deceiving in more ways than one.

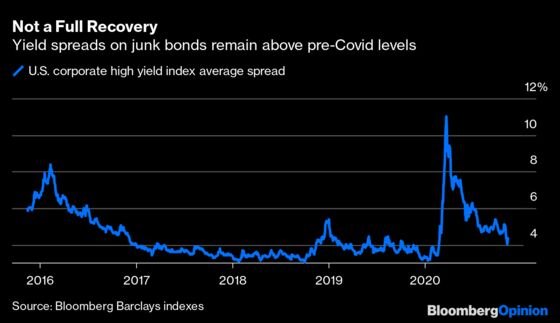

For starters, credit investors tend to focus primarily on the yield spread above U.S. Treasuries. The average maturity of the high-yield index is 6.4 years, so the seven-year Treasury note is a decent benchmark. That rate has climbed to 0.64% from as low as 0.355% in early August, but the current yield is still well below historical market levels. From that perspective, it’s only natural that all-in yields on junk bonds would be lower as well. But the average spread, in contrast to yields, still hasn’t recovered to pre-Covid levels.

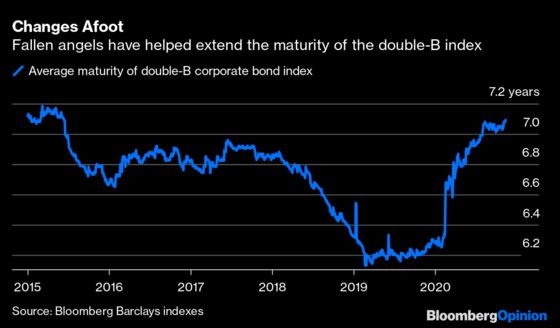

There’s also the undeniable fact that indexes can change — often dramatically — during periods of intense credit pressure. As Bloomberg News’s Katherine Greifeld noted last week, three of the five largest companies in the high-yield index are behemoths that entered the year with investment grades but since became “fallen angels.” Those three — Ford Motor Co., Occidental Petroleum Corp. and Kraft Heinz Co. — are still rated in the double-B tier. And investors see Ford and Kraft in particular as relatively safe bets: Ford bonds due in 2026 yield just 3.5%, while Kraft Heinz debt with a similar maturity yields just 2.4%. The increased proportion of these higher-rated junk bonds would seemingly bring down the overall index yield.

But even that doesn’t quite tell the entire story. Because investors are typically willing to lend money to investment-grade companies for decades, while shortening the leash on junk-rated borrowers, the proliferation of fallen angels has pushed the average maturity on the double-B portion of the high-yield index to its highest level since 2015. That’s because it now includes Kraft Heinz debt due in 2042, 2045, 2046, 2049 and 2050, plus Ford bonds maturing in 2046 and 2047. When looking at those securities, yields don’t look quite so low. Ford’s longer-dated bonds yield 7.27%.

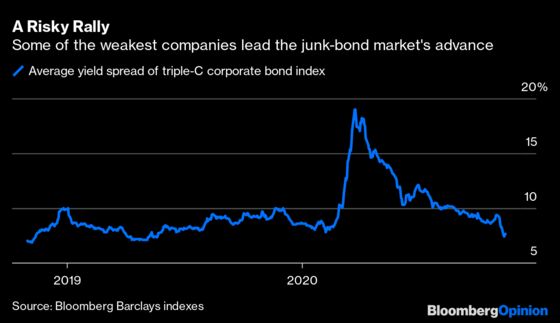

Then there’s the most volatile part of all: The triple-C rated component of the high-yield index. These bonds collectively make up just about 12% of the broad index. But when spreads compress by a whopping 70 basis points in one day, as they did Nov. 9, and almost 200 basis points in a week and a half, that’s going to leave a mark. Shockingly, while spreads in higher-rated portions of the speculative-grade market remained elevated relative to the start of this year, spreads on triple-C debt last week touched the lowest since May 2019, and nearly reached a point unseen since late 2018.

It’s hard to get a clean read on what exactly is happening here, given the propensity for turnover in this part of the index. For example, WeWork Cos. bonds maturing in 2025, which yield almost 20%, recently left the triple-C index after Fitch Ratings dropped their grade to CC from CCC. The debt is now the eighth-largest part of the index of corporate securities on the brink of default. Meanwhile, bonds due in 2024 from Six Flags Entertainment Corp., which were previously part of the single-B index, are now in the triple-C index after a S&P Global Ratings downgrade in late September. They yield just 5.6%.

Put together, it’s too soon to declare an all-clear for highly leveraged companies just because top-line yields have dropped so much. Obviously, it doesn’t hurt to have borrowing costs near all-time lows. Investors need only look to debt and stock offerings from travel businesses such as American Airlines Group Inc. and Carnival Corp., and energy companies including Continental Resources Inc. and Antero Midstream Corp., as evidence that the capital markets are helping firms across industries prepare for hard months ahead before a Covid-19 vaccine is widely available.

It’s risky, though, to assume that the shakeout of highly leveraged businesses is over and done. As I wrote last month, junk bonds aren’t going to save every company from going bust — liquidity is important, but so is solvency. Perhaps the most crucial lesson of all, however, is that the bond market isn’t a monolith, no matter how many billions of dollars of debt change hands through portfolio trading. That means a number like 4.56% can only convey so much.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.