(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Big banks are rolling in free cash, but investors are struggling to believe that some of them will ever hand it over. They should take another look.

Fifteen of the biggest U.S. and European banks have piled up more than $125 billion of excess capital after the first nine months of 2021. Profits soared after a spell of record corporate dealmaking, rallying financial markets and fading fears of debt defaults. But for a time, lenders were blocked from buying back shares or paying dividends.

Now, even though these billions are apparently free to be dished out to shareholders, some banks trade as if investors haven’t noticed.

Take UniCredit: The Italian lender reckons that by the year’s end it will have 2 percentage points more equity capital on its key measure of balance sheet strength than it wants or needs. That excess is currently worth about 6.6 billion euros ($10.4 billion), money that ought to be paid to shareholders.

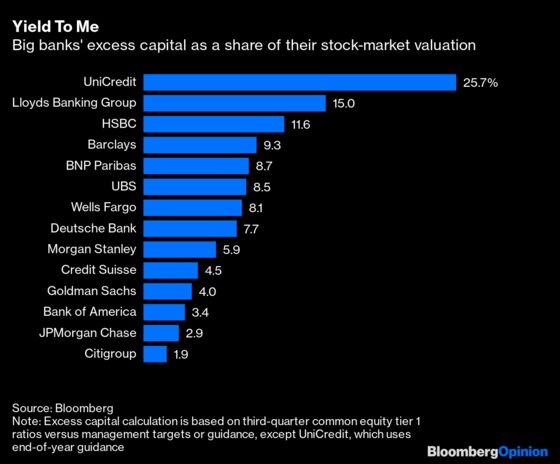

But the bank trades at a hefty discount to its forecast book value: The excess capital is worth more than one-quarter of its stock-market value. In other words, UniCredit is trading with a potential cash return yield of nearly 26%.

That is exaggerated but not exceptional. Looked at the same way, Lloyds Banking Group of the U.K. has a potential yield of 15%; Britain’s HSBC yields nearly 12%; Barclays, BNP Paribas and UBS are all around 9%.

At the other end of the table, JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Citigroup Inc. both yield less than 3%, though for different reasons. JPMorgan has more than $14.5 billion in excess capital, the second most after Wells Fargo & Co., but it trades at the highest valuation, nearly two times forecast book value. Citigroup trades at a European-style discount to book value but has much less spare capital than peers.

The industry ended up with all this money because protecting capital has been the obsession of regulators and banks since the financial crisis of 2008. Known as common equity tier 1 in its most reliable form, this capital is there to soak up losses. More capital means banks are less likely to beg for bailouts.

When the Covid-crisis hit, banks doubled down on protecting common equity capital by diverting billions of last year’s profits into provisions for an expected wave of losses on bad loans. With this year’s recovery many of those provisions are being released, especially in the U.S. and U.K. Banks are now earning last year’s profits and this year’s together.

So why do investors trust some banks to pay out this cash and not others? In some cases, the capital could evaporate; in others, it’s more about skepticism or uncertainty or both.

U.S. banks have been quicker to restart big buyback programs — although Europeans have begun to lift payouts too — and most have billions of dollars left. Morgan Stanley, for example, had something like $11 billion of spare capital at the end of the third quarter. (Unlike some peers, it doesn’t target a specific capital ratio, but Chief Executive Officer James Gorman has given rough ranges on analyst calls.)

But the bank trades at a high-looking yield of nearly 6% for this money and that’s because it said at third-quarter results that more than half of this excess will be consumed by capital-rule changes it is adopting, which will standardize some measures of risk, inflating the size of some banks’ balance sheets. At Goldman Sachs, the same rules are expected to cut about one-third of its current excess.

It’s a similar story at BNP Paribas and Societe Generale, where European capital rule changes that set minimum capital levels for some exposures are expected to eat up large chunks of current spare capital.

At UBS, another high-yielder, there is more than $5.5 billion of excess, but the Swiss bank and its investors are awaiting a court to rule on its appeal of a multibillion euro fine in France.

High yields are a bit more of a puzzle at the British banks, especially Lloyds, which is sitting on about $7 billion. It expects to take regulatory changes in its stride, and it has among the highest returns on equity of any big bank so far this year – even if we strip out provision releases. This illustrates just how unloved British stocks are among investors.

And what about UniCredit, the highest yielding of the lot? Well, it has a lot to prove. Much of its excess could be burned in European rule changes — it hasn’t yet given guidance. Also, CEO Andrea Orcel, a former investment banker, has to show he won’t prove trigger happy on takeovers.

Investors already trust U.S. banks to hand back spare capital quickly and efficiently. But there are billions potentially to come out of some European banks too. Investors should look again at just how cheaply some of those potential paydays are trading.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Paul J. Davies is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering banking and finance. He previously worked for the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.