Boris Johnson’s Message to Business Is Still Unprintable

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- When Boris Johnson famously said “f*** business” back in 2018, he was ostensibly referring to corporate lobbyists who weren’t getting his Brexit message. Businesses would have to adapt to the new Brexit reality, not the other way around.

For any who didn’t get the memo the first time around, this week’s Conservative Party conference in Manchester has been a refresher course. Faced with crippling shortages of truck drivers, care-workers, abattoir staff and other professionals, ministers have largely suggested it’s a failure of industry leaders to invest in a domestic workforce. Try harder, is the message.

Johnson warmed to the theme in a testy BBC radio interview Tuesday, saying businesses had been “mainlining” cheap EU labor for too long. And he doubled down in a crowd-pleasing conference speech Wednesday that breezed past what he dismisses as the short-term strains of the pandemic. Instead of mass immigration, he said Britain can now look forward to higher wages, higher levels of productivity and better working conditions.

That message shows just how long a shadow Brexit will cast over British policy, and how far the Tory Party has moved from the self-appointed guardians of “a nation of shopkeepers” under Margaret Thatcher. The eff-business stance has certainly been useful. While there’s never been much evidence that EU immigration led to reduced wages or employment opportunities for domestic workers, the Brexit campaign’s depiction of immigrant labor crowding out British workers hit home. Wages had long been stagnant by that time; giving voters both a diagnosis and a cure proved highly effective.

It’s no wonder now that Johnson — who will need to show at the next election that Brexit has brought benefits — is hailing wage increases as an early Brexit dividend or chiding companies for failing to prepare for tighter labor markets. His bet is that people will be happier about rising wages than they will be worried about supply shortages and higher costs of living.

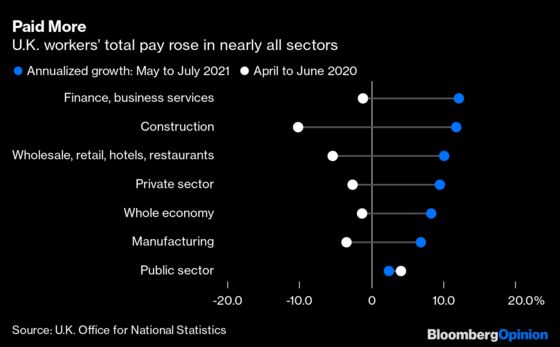

But prices are rising nearly as fast as wages and may soon outpace them. The Bank of England reckons underlying pay growth is running at around 4%, which is still ahead of inflation but not by much. Inflation too is expected to hit that level by the end of the year. While average pay, excluding bonuses, is growing around 6.8%, as the Office of National Statistics notes, that number is deceptive because it reflects base effects (where current levels are compared to unusually low pandemic levels) and compositional effects (fewer lower paid jobs mean a rise in average earnings).

If businesses do respond to Johnson’s call for more wage hikes, there are other risks. An inflationary spiral — where rising prices lead to higher wage demands — is one that Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey says he takes seriously even if he thinks current pressures will prove temporary. Maybe Johnson should too, given the impact a small increase in interest rates would have both on mortgage holders in this nation of home-owners and on government debt servicing.

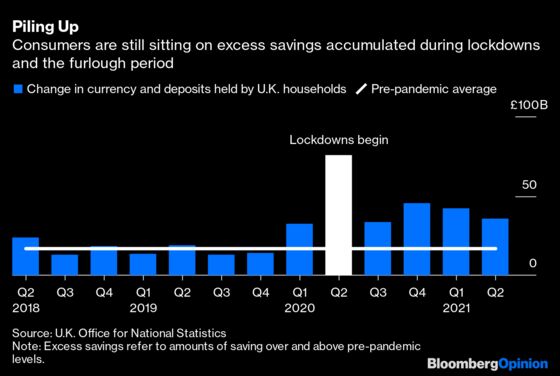

And the wage hikes are not evenly distributed across sectors. Those on lower incomes, disproportionately in the north of the country where Johnson took a large share of the 2019 vote, are likely to be hardest hit by rising energy prices, the end of furlough and the 20-pound ($27) weekly uplift to welfare payments. While consumers are still sitting on excess savings from the lockdown and furlough period, anticipation of rising prices will impact discretionary spending.

Johnson is a master of shifting blame and changing the subject. But far better for the government to work with businesses to drive up not just wages, but the supply side changes that would put Britain’s economy on a better growth trajectory and deliver the rebalancing he’s promised.

While economic theory says that people are paid according to the value of their labor, there is evidence to suggest that rising wages could have a positive impact on productivity. Workers may be more reluctant to leave well-paid jobs, reducing turnover costs, and more likely to reciprocate better remuneration with increased diligence. Companies may invest more in a workforce they want to retain and reward well.

But those are the easy yards. “What is clear to me is that for some jobs productivity is not the point,” says Kitty Ussher, Chief Economist of the Institute of Directors and a former Labour MP. “Examples are care, health and some parts of the retail and hospitality sector where it’s the quality of customer/patient interaction that matters, not necessarily the financial efficiency.” In that case, it’s crucial that those employed in lower-paid sectors are sufficiently skilled to get higher productivity jobs.

Closing Britain’s large skills- and training gap will require substantial government inducements, from infrastructure improvements to educational offerings. So far, the commitment has been piecemeal. Ussher notes that while the March budget included a new “superdeduction” for investment in plant and machinery, there is no similar incentive for the investment in human capital that businesses are being urged to make.

Companies looking at steep increases in energy, taxes, Brexit effects and other costs may also be more cautious about hiring and investing — especially if they suspect consumers hit by rising costs won’t be spending as freely, despite some pandemic savings. In its latest survey of company directors, the Institute of Directors found a 23 point drop in confidence between July and September.

Johnson’s dogmatic stance on immigration is only adding to pressures. Brexit gave Britain control of its borders, but locking out much-needed workers makes little sense (and offering a few thousand short-term visas hasn’t proved much of an inducement). “Many Brexiteers, myself included, have vocally advocated for liberal immigration, while those who want strong controls on immigration do not want a shortage of goods, a lack of carers or rampant price inflation,” Simon Wolfson, chief executive officer of the retailer Next Plc, wrote in the Evening Standard.

Wolfson rightly notes that higher wages are useless if there are no workers to fill the jobs. Businesses, he says, should be allowed to hire foreign workers provided they pay them the same wages as domestic workers along with a special visa tax, which would help the market correct for current shortages without disadvantaging British workers.

While few politicians speak directly about Brexit these days, it’s nearly always a presence in the room. It was the movement that brought Johnson to power; part of his governing project is to keep a certain flame alive to remind Tory voters of the wisdom of that decision. It’s creating ongoing problems in Northern Ireland and Brexit tensions threaten to exacerbate the energy crisis since the U.K. relies on France for some of its power supply.

Businesses may seem a useful whipping boy for the supply-chain pressures that clouded what Johnson hoped would be a celebratory conference in Manchester. But when the theatre of conference season is over, he will have to listen more than lecture if he’s to find better solutions to unleashing the supply-side of the economy.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Therese Raphael is a columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. She was editorial page editor of the Wall Street Journal Europe.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.