Jobs Report Makes a March Fed Rate Hike Nearly a Done Deal

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Only a few hurdles remain before it’s safe for bond traders to assume that the Federal Reserve will start raising interest rates in March. The U.S. economy just cleared a big one with the latest report on the labor market.

Yes, the top-line payrolls figure failed to live up to lofty expectations, with U.S. employers adding just 199,000 workers in December, compared with the median estimate of a 450,000 gain in a Bloomberg survey of economists. But that looks like a reflection of harsh seasonal adjustments from the Bureau of Labor Statistics — the rest of the jobs report was unambiguously strong. As it did in the November report, the household survey told a much more optimistic story about the labor market, with the unemployment rate tumbling to 3.9%, beating projections for a dip to 4.1% and another big step toward the 3.5% level that Fed officials see prevailing from the end of the year through 2024. Average hourly earnings jumped 4.7% from a year ago and 0.6% from November, both handily outpacing the median forecast.

For traders who are trying to pinpoint the Fed’s path of tightening, it all boils down to the calendar of the most-important economic releases relative to the central bank’s coming policy decisions — and the December jobs report was the first important economic indicator of 2022. Next up: the latest consumer price index data, which is expected to show a 7.1% increase from a year ago and 5.4% when excluding volatile food and energy prices. Both measures would be higher than November’s figures, which reached levels unseen in decades. Two weeks later comes a Federal Open Market Committee decision that won’t be eventful on its own but should set the scene for the following meeting in March.

The central bank goes to painstaking lengths to signal to markets that it’s about to do something meaningful. Think back to June 2019, for instance, when Fed Chair Jerome Powell made clear that it was on the verge of cutting rates the next month (it did). Or January 2019, when the policy statement stressed that officials “will be patient” about adjusting rates, which foreshadowed an abrupt shift to projecting zero rate increases for that year, compared with two in their previous forecast.

With a 3.9% jobless rate and inflation that’s expected to remain way above target, it stands to reason that the Fed could insert some language into its next statement suggesting that raising the fed funds rate “may soon be warranted” (the same phrase used after the September meeting to indicate tapering would begin in November). Barring any significant economic setback, that would prime markets for a March increase.

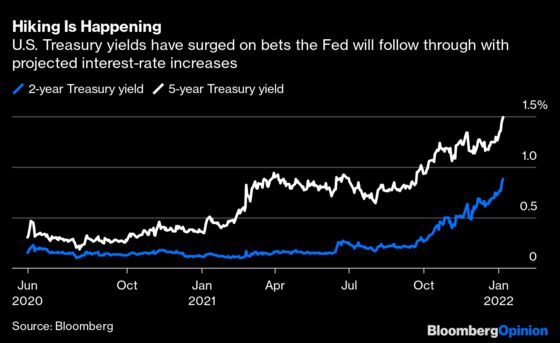

St. Louis Fed President James Bullard took such a stance on Thursday, arguing the FOMC should “begin increasing the policy rate as early as the March meeting in order to be in a better position to control inflation.” Fed Governor Christopher Waller said bluntly in late December that “March is a live meeting for the first rate hike.” The bond market, for its part, priced in a greater than 80% chance of such a move after Wednesday’s release of December’s FOMC minutes. The five-year U.S. yield topped 1.5% after Friday’s jobs data, up from 1.3% at the start of the week.

Those minutes are even more critical to reread now that December’s employment data is in hand. Here are two key passages on how Fed officials saw the labor market at the time:

“Many participants judged that, if the current pace of improvement continued, labor markets would fast approach maximum employment. Several participants remarked that they viewed labor market conditions as already largely consistent with maximum employment.”

“… maximum employment, a condition most participants judged could be met relatively soon if the recent pace of labor market improvements continued. A few participants remarked that maximum employment consistent with price stability evolves over time and that further improvements in labor markets were likely over subsequent years as the economy continued to expand. Some participants also remarked that there could be circumstances in which it would be appropriate for the Committee to raise the target range for the federal funds rate before maximum employment had been fully achieved — for example, if the Committee judged that its employment and price-stability goals were not complementary.”

Fedspeak is a language unto itself. Note “several” officials said at the time that the U.S. economy had pretty much already cleared the “maximum employment” threshold for raising interest rates and “most” expected it would hit that goal “relatively soon.” The December jobs data is yet another step in the right direction, and when put in the context of the minutes, it suggests a majority of policy makers would be on board with declaring both conditions of the dual mandate satisfied come March.

The wild card in all of this is the employment cost index for the fourth quarter, which will come out on Jan. 28, two days after the FOMC decision. The broad gauge of wages and benefits across the U.S. increased 1.5% in the third quarter compared with the three months through June, the largest increase on record and reflecting a nearly 6% annualized pace. It was so shockingly large that Powell said he considered increasing the amount of tapering at the November meeting, which took place just days after the data was released, but ultimately chose not to because officials had so clearly “socialized” the initial pace.

If for whatever reason the ECI data slows more than expected, the Fed might feel less urgency on raising rates. Still, December’s wage data beat estimates by an impressive margin, and November’s figures were revised higher. Aggregate wage income, which combines payrolls with hourly earnings and hours worked, was up almost 10% in December relative to a year earlier. For central bank officials, there’s little reason to think ECI will seriously disappoint.

The fact remains that the Fed is in a weird, uncomfortable place as the U.S. approaches two years of living with the Covid-19 pandemic. Inflation isn’t transitory. The central bank is still buying tens of billions of dollars of bonds a month while simultaneously deliberating about a balance sheet runoff that “would likely be faster than it was during the previous normalization episode.”

It’s the new year and way past time to clean up the narrative. The U.S. economy is in an inflationary boom and the Fed is ready to move interest rates off the zero lower bound. A 3.9% unemployment rate, even with subdued headline job gains, is consistent enough with “maximum employment” that the central bank needs to tighten monetary policy to reduce inflation and promote a long expansion that’s “broad based and inclusive” and brings more people into the workforce. Powell’s December press conference and the FOMC minutes said all of this, but now it’s about taking action as soon as possible. Given the deliberate nature of the Fed, that makes March 16 the flashpoint.

More From Other Writers at Bloomberg Opinion:

- Biden’s Economic Performance Is Unbeatable: Matthew Winkler

- The Fed Can’t Make People Go Back to Work: Michael R. Strain

- The Biden Economy Is Actually Doing Pretty Well: Karl W. Smith

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.