Why Jerome Powell Absolutely Loves This Jobs Report

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- October’s U.S. employment report was strong in virtually every respect — a sorely needed jolt of confidence in the labor market after months of missed forecasts and hand-wringing about vacant jobs. It also backed up some notable comments from Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell earlier this week when he was asked how to define “maximum employment.”

That term, of course, is one of the bedrocks of the central bank’s new policy framework for raising interest rates. Powell said at his press conference Wednesday that the labor market is “clearly not” at a level the Fed deems consistent with full employment. That’s almost certainly still the case even after the latest figures, which showed nonfarm payrolls increased 531,000 last month and were revised higher by 235,000 in the previous two months, causing the unemployment rate to fall to 4.6%. For context, that’s lower than the rate in December 2016, when policy makers embarked on two years of tightening.

Still, traders and economists have long understood that the Fed has a different view this time around. Among the lessons learned from the last cycle: The jobless rate that generates inflation seems to be far lower than previously estimated. For a while, Fed officials highlighted the pre-pandemic employment-to-population ratio as a potential indicator of when the economy would hit maximum employment.

With a bit of rhetorical flourish, Powell appeared to shift away from that framing this week. “The temptation at the beginning of the recovery was to look at the data in February of 2020 and say, ‘Well, that’s the goal because that’s what we knew’ — we knew that as achievable in a context of low inflation,” he said. “There’s room for a whole lot of humility here as we try to think about what maximum employment would be. ... We have a completely different situation now where we have high inflation, and we have to balance that with what’s going on in the employment market.”

Saying it’s tempting to do something is a classic setup for explaining why it would be misguided. In this case, Powell seems to be pushing back on the idea that there’s a specific pre-pandemic level in any metric that must be met before the Fed raises interest rates. The idea behind the central bank’s new framework was that the U.S. economy could tolerate a hotter jobs market without a sharp increase in inflation. Now, Powell acknowledged, “the level of inflation we have right now is not at all consistent with price stability.”

That lowers the bar for reaching maximum employment — a crucial shift as bond traders think about when the Fed will potentially start increasing interest rates.

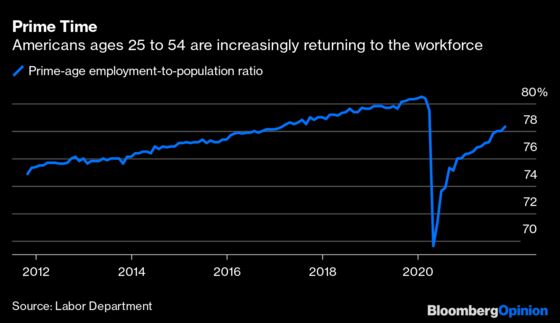

Consider the prime-age employment-to-population ratio of adults ages 25 to 54. Whereas some officials were previously looking at the workforce as a whole, Powell acknowledged there’s “a significant number of retirements,” in contrast to the last cycle in which people were “just not retiring at the rates they were expected to retire. So, maybe this was just catch up on that.”

Prime-age EPOP jumped in October to 78.3% from 78% in the previous two months. If that kind of increase were to continue on average month after month, the ratio would eclipse its January 2020 high in June — precisely when the Fed’s tapering is set to end. By contrast, overall EPOP rose to 58.8% in October from 58.7%. At that pace, it would take almost two full years to get back to pre-pandemic levels.

Yes, the number of jobs is still some 4.2 million below the early 2020 peak. But as Peter Boockvar, chief investment officer for Bleakley Advisory Group, put it: “We know though that many people that make up the difference are not coming back, whether they’ve retired or there is some other reason, so hoping for a pre-Covid labor force repeat is completely unrealistic.” Fed officials might not deem it out of the realm of possibility, but they’ve subtly pivoted to acknowledge that getting back to those lofty heights might not be the stringent definition of maximum employment they once assumed.

The reaction in the U.S. Treasury market suggests something similar. Most strikingly, yield curves are flattening again — a sign that traders expect the Fed and other central banks to ultimately step in and gradually tighten policy to prevent inflation from overheating. Now, two-year U.S. yields still remain below levels from last week, but overall the expected path of rate increases hasn’t changed much within short-term rates markets, which forecast about two 25-basis-point moves higher next year.

This jobs report indicates the labor market remains solid and is on track to get even stronger into next year. The Fed’s taper timeline gives policy makers eight months to see how the economy rebounds from the pandemic. When that time expires, it looks increasingly likely that the central bank’s criteria for starting to raise rates will be met on all three fronts.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.