Jeremy Corbyn's Four-Day Week Is Not Such a Bad Idea

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- You can’t accuse the U.K.’s opposition Labour party of being dull on economics. Since Jeremy Corbyn became leader in 2015 and picked John McDonnell – an avowed socialist – as Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, a long list of quirky ideas has issued forth.

Labour is thinking about re-nationalizing the country’s rail, energy and water industries, changing the remit of the Bank of England to include a productivity target, and introducing a universal basic income. And now it’s toying with a four-day work week for lucky Brits. Robert Skidelsky, an economic historian and biographer of John Maynard Keynes, is putting together a report on the subject that’s due in July. McDonnell is interested and may end up making it official party policy.

A sharp reduction in working hours isn’t new exactly, so there are plenty of historic and international examples to guide Skidelsky. The evidence suggests that letting people work less is a poor way to boost employment, but may improve productivity. Since the British economy is very good at creating jobs, but very bad at boosting efficiency, a four-day week may appeal.

Yet there still isn’t a huge amount of empirical data to show just how much of a lift fewer hours would give to staff productiveness. As such, it’s probably too early for the U.K. to experiment with a four-day week across the public sector – something Skidelsky is looking into. It would be far better to let companies test the idea individually (which is already in train) before making the change for state employees.

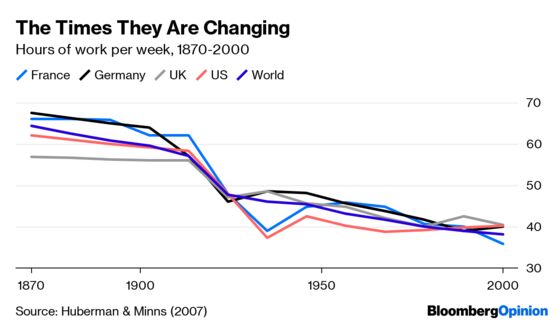

It’s not as if the working week has been left untouched in modern times. The number of hours worked around the world has fallen sharply over the last century and a half. Michael Huberman and Chris Minns, two economic historians, found that the average full-time worker toiled for more than 64 hours in 1870, and just 38 in 2000. In Britain, the trend is less pronounced but striking still: Weekly hours have fallen from 57 to 40.5. These gains in leisure time were accompanied by a phenomenal rise in global income, thanks to huge increases in productivity in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries – inspiring Keynes’s famous prediction that technological improvements would lead eventually to a 15-hour work week.

The biggest question for McDonnell and Labour will be what purpose they’d want a cut in hours to serve? Pasquale Tridico, the head of Italy’s social security institute and an adviser to Italy’s populist labor minister Luigi Di Maio, advocates reducing the working week to spread the same amount of employment across more workers and hence cut joblessness. But several studies reject this idea. For example, Matthieu Chemin and Etienne Wasmer, two economists, looked at France’s 35-hour week and found no positive effects on employment. Similar studies in Germany, Canada and Chile reached the same broad conclusion.

Yet joblessness is hardly a problem for Britain anyway. Its employment rate for those aged between 16 and 64 has climbed above 76%, the highest level on record.

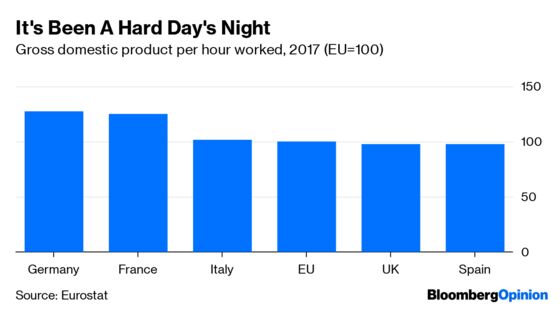

Productivity, though, is a deep concern for the U.K. In 2017, the average British employee produced 2.1% less output per hour than the average European Union worker. In France (with its 35-hour week), productiveness was 24.8% higher than the EU average, according to data from Eurostat; it was 27.6% more in Germany.

The most recent empirical literature finds that cuts in working hours are indeed connected to higher productivity. One study looking at Britain during World War One found that productivity increased alongside the number of hours worked up to a certain threshold, only to fall afterwards because of fatigue.

The economists Marion Collewet and Jan Sauermann have examined a more recent dataset of call center agents in the Netherlands. They found that an increase in the number of hours by 1 percentage point leads to an increase in output (as measured by calls answered) of just 0.9 percentage points. So piling on more hours leads to a loss in productivity. In fairness to hard-driving employers everywhere, the researchers also say that doing more hours is associated with higher quality on the job, showing that this isn’t a straightforward subject.

Still, the overall research suggests that cutting back on hours worked might indeed be positive for productivity. Yet the quality of the studies doesn’t seem robust enough for a drastic solution, such as rolling out a four-day week for U.K. state employees. Several private sector companies are already experimenting with a shorter week and some are reporting productivity gains. They say workers feel more motivated and have greater loyalty so tend not to quit.

If this is indeed the case, one would expect more firms to move to shorter hours. Only when there’s critical mass, should the public sector follow suit. Until that happens, Labour would be wise to hold fire – and delay Keynes’s dream a little longer.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Ferdinando Giugliano writes columns on European economics for Bloomberg Opinion. He is also an economics columnist for La Repubblica and was a member of the editorial board of the Financial Times.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.