Vinik Failed to Resurrect a Hedge Fund. Who Needs One?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Don’t count on a comeback for equity hedge funds.

That appears to be the conclusion Jeffrey Vinik reached when he decided recently to close Vinik Asset Management. He resurrected the hedge fund earlier this year after closing it in 2013.

The move to reopen the fund was a bold act of defiance when investors are dumping stock pickers, including equity hedge funds, in favor of low-cost index funds. “I think this is an incredible opportunity for old-fashioned stock picking,” Vinik told CNBC in January. “We’ve had decades, maybe 10 or 20 years, of active managers underperforming passive managers.”

So what happened? “Simply put, it has been much harder to raise money over the last several months than I anticipated,” Vinik said in a letter to investors, adding that performance hasn’t been strong enough to entice new investors.

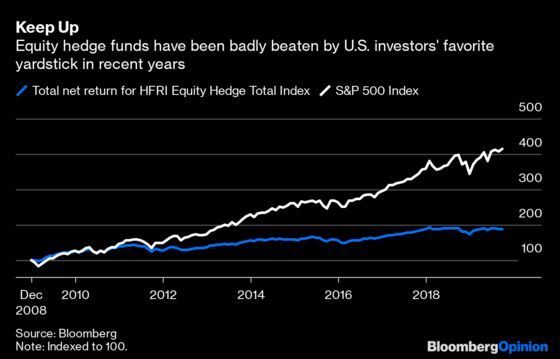

But performance isn’t exactly the issue. Yes, as any portfolio manager can attest, U.S. investors have a bad habit of comparing every investment to the U.S. stock market — by which they usually mean the S&P 500 Index — even if it’s not an appropriate yardstick. So it probably didn’t help that the S&P 500 outpaced Vinik’s fund by roughly 4 percentage points, including dividends, since the fund began trading on March 1. More broadly, the S&P 500 has beaten equity hedge funds by 8.1 percentage points a year since 2009, as measured by the HFRI Equity Hedge Total Index.

The bigger problem is that no one needs equity hedge funds anymore. As I pointed out in January when Vinik announced the relaunch of his fund, investors can turn to low-cost funds for nearly every style of stock picking, including long-short strategies favored by hedgies that call for simultaneously betting on some stocks and against others. During hedge funds’ heyday in the 1990s and 2000s, those options were scarcely available.

There are already 19 exchange-traded funds in Morningstar’s long-short equity category. They’re relatively new — 13 have a two-year track record, 11 have a three-year record and only four have been around for five years — but they’re already proving to be formidable opponents. Their average return beat the HFRI index by 0.6 percentage points annually over two years through September, 0.8 percentage points over three years and 0.9 percentage points over five years.

It’s not that long-short equity ETFs have a better mousetrap — they simply charge lower fees. Their average expense ratio of 0.85% a year is a fortune in ETF land, but it’s a bargain compared with the traditional 2% of assets and 20% of profits levied by hedge funds. It’s hard to see how hedge funds make up that difference plying the same strategy.

So while it’s true that there’s little interest in strategies that bet against stocks during a raging bull market like the one the U.S. has enjoyed since 2009, investors have little use for hedge funds even if long-short strategies shine during the next downturn, as is widely expected.

Like Bjorn Borg returning to tennis in 1991 after retiring 10 years earlier, armed with a wooden racket when other players wielded a superior graphite one, Vinik must have realized that the game had passed him by. “I very much doubt I will go back into the hedge fund business,” he said.

Equity hedge funds don’t have to disappear. They could lower their fees, for starters. There will also be a handful of stock pickers who overcome their princely fees by making prescient, concentrated bets. Everyone else in the bloated $800 billion equity hedge fund industry would do well to heed Vinik’s example.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.