(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As Israelis and Palestinians keep clashing in the Middle East, their conflict also spills onto streets from Canada to France and the U.K. But nowhere in the West is the strife more excruciating than in the nation that once perpetrated the Holocaust.

In recent days, thousands of protesters have thronged the streets of several German cities, shouting abuse not only at Israel but also against Jews in general — and using tropes of anti-Semitism too vile to repeat here. At one rally, an Israeli woman who is a journalist was physically attacked. And although these were diverse mobs, many marchers were young Muslim men of Arabic background, whether they had German citizenship or not.

The reaction from mainstream German society was swift. Public figures and politicians across the party spectrum emphasized that while criticism of Israel and its policies is covered by the freedom of speech, hatred of Jews is unacceptable and intolerable.

Even the far-right Alternative for Germany, a party often suspected of pandering to both anti-Semitism and anti-Muslim xenophobia, spoke out, twisting the circumstances to serve its ugly purposes. If we’re serious about fighting anti-Jewish prejudice, said Alexander Gauland, one of its leaders, we have to “stop uncontrolled Islamic mass immigration and deport the criminals.”

Gauland’s logic takes a demagogic turn. Nonetheless, he put his finger on one of the most sensitive topics imaginable: the fraught psychological geometry between Germans, Jews and Muslims. What makes this triangle so agonizing — and leaves so many Germans groping helplessly for appropriate words and emotions — is the legacy of the Holocaust.

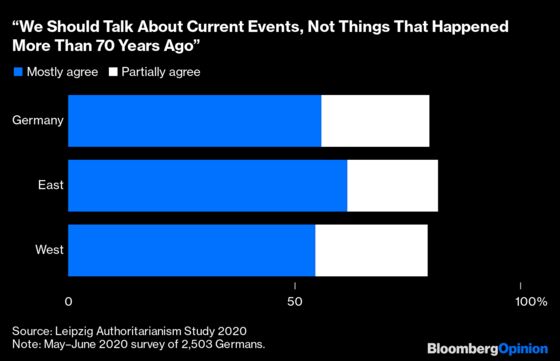

Postwar Germany was built in large part on atonement for Auschwitz. Germans drew two main lessons from their national crime. For a long time these didn’t conflict, but nowadays they do.

The simpler lesson of history was: Never again discriminate against Jews, and help protect them wherever they are, whether in Berlin or Tel Aviv. You could call this the particularist form of remembrance and responsibility.

But there was also a generalized version: Never again discriminate against any minority, and give succor to the oppressed wherever they are, whether in Berlin or Gaza. In this form, the moral imperatives of German atonement cover Muslims as well. I vividly remember such sentiments in my conversations with Germans during the refugee crisis of 2015, when the country — at least for a while — prided itself on its “welcome culture” toward the arriving Syrians and Afghans.

This national moral compass hasn’t eradicated endemic anti-Semitism and prejudice, however. Researchers at Leipzig University found that xenophobia has declined, but lingers. In what used to be West Germany, it decreased from 21.5% to 13.7% of the population between 2018 and 2020. In the formerly communist East, where Germans largely missed out on the postwar atonement culture, it waned from 30.7% to a still disheartening 27.8%.

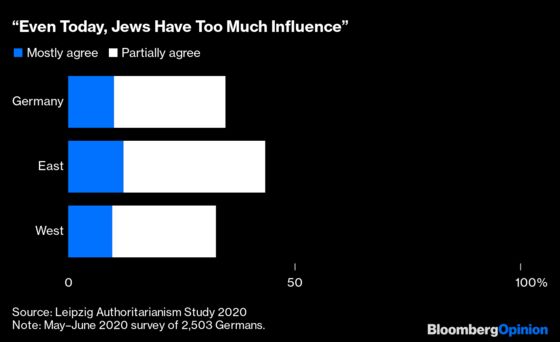

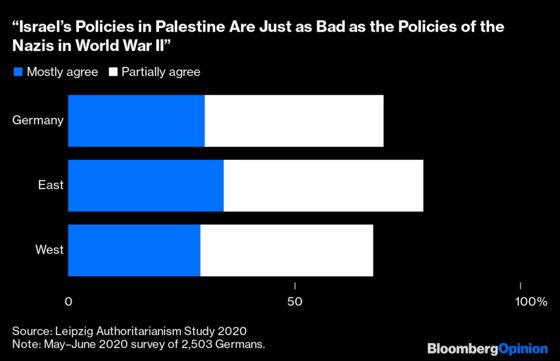

More specifically, more than one in four Germans still agreed with the statement that Muslims should be banned from immigrating to Germany. And anti-Semitism, overt or subtle, remains unnervingly widespread among Germans overall (see charts).

Even if prejudice among ethnic Germans is stable or trending down, its manifestations appear to be growing more violent. Many Jews report feeling less safe. The most shocking incident, on Yom Kippur in 2019, was an attempted massacre by a white supremacist in a synagogue in the eastern city of Halle. He failed to break down the barricaded door, but he then randomly gunned down a woman and a man elsewhere.

Germans have no problem denouncing their native-born anti-Semites, but the imported strain presents new problems. For a long time, the German mainstream didn’t know how to label or discuss the prejudices and misogyny that some Muslim immigrants brought with them.

To point the finger too bluntly at Muslims from Arab cultures would be unfair, because most Muslims are neither anti-Semitic nor misogynist. It would also be a sin against the generalized lesson of the Holocaust — never again discriminate or stereotype.

And yet, after the ugly scenes this week, many mainstream politicians are now overcoming the customary German reticence in discussing these matters. A leader of the center-right Christian Democrats bluntly observed that German anti-Semitism now has three main sources — the far right, the radical left, and some Muslim immigrants — and that all three must be fought equally. Armin Laschet, the party’s boss and candidate for chancellor, averred that all Germans, including Muslims, share in the moral legacy of the Holocaust.

If anything good is to come out of this latest round of conflict, it may be that Germans of all faiths will now renew their collective effort against prejudice, but with more honesty — and that people in other countries do exactly the same.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andreas Kluth is a columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. He was previously editor in chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for the Economist. He's the author of "Hannibal and Me."

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.