(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Soaring copper, lumber and agricultural prices are boosting inflation in a way that exceeds what some economists had anticipated. Federal Reserve officials have reiterated their belief that these price spikes are “transitory,” but what if they have it wrong in not accounting for labor dislocations, supply-chain logjams, and a new environment in which the market is addicted to the Fed’s support?

Bloomberg Opinion columnist John Authers, Bloomberg Surveillance anchor and Bloomberg Opinion columnist Lisa Abramowicz and senior commodities reporter Jack Farchy offered their insights on whether or not the Fed is behind the curve. Their remarks have been edited and condensed.

What does the Fed have wrong?

ABRAMOWICZ: The better question is which risk is more realistic right now: disinflation or rapid inflation. The Fed says disinflation. Markets increasingly disagree.

It’s easy to understand where the Fed is coming from. Central bankers have been conditioned by years of overestimating the pace of rising prices. They’ve contended with globalization, aging demographics and swelling debt loads that have tamped down potential inflation despite money printing and ultra-low rates. But markets are looking at a new paradaigm, one of disrupted supply chains, new technologies, massive fiscal spending and social programs aimed at boosting lower-wage incomes.

Which brings us to the question at hand: Which is the more pernicious risk, inflation that’s too low or too high? At this point, very high inflation would puncture valuations in a global bond market that exceeds $128 trillion. Relatively stagnant prices would leave companies and countries saddled with record amounts of debt, unable to grow (or inflate) their way out of it.

The answer to this depends on the pace of inflation. If it skyrockets, it could be as damaging as slowing growth, or even worse. The Fed, however, is worried about a world unable to crawl out from under its massive burden of debt, leaving the world a less dynamic and more unequal place.

FARCHY: At his last press conference, Jay Powell set out two reasons for thinking a rise in inflation should be transitory: the base effect of a comparison with last year’s depressed prices; and bottlenecks that are “temporary and expected to resolve themselves.”

When it comes to commodity markets, he’s clearly right that there is a significant base effect -- April 2020, after all, was when oil prices turned negative. But commodity prices are also high by comparison with less extreme moments in history. Iron ore and copper have hit all-time highs. Corn prices this month traded within 15% of their all-time highs. The Bloomberg Commodity Spot Index has only been higher than today’s level twice in history: in July 2008, just before the financial crisis, and in mid-2011, at the high point of the China-led supercycle.

It is also true that commodity markets are cyclical: When prices rise, producers respond by producing more, and so eventually prices fall again. As the old trader’s adage goes: The best cure for high prices is high prices.

But it’s far from obvious that the rise in commodity prices can be explained away by short-term bottlenecks. Yes, trade flows have been disrupted by things like the Suez Canal closure and the shortage of shipping containers. Yes, some commodity production -- for example, mining in Chile and Peru, and meatpacking in the U.S. -- was affected by outbreaks of Covid last year.

But there are also longer-term trends: low investment in new supply by oil companies and miners, amid pressure from shareholders to pay higher dividends and to invest less in fossil fuels. And potential for an extended period of strong demand that has some on Wall Street calling for a new supercycle.

The supercyclists may be wrong, but it’s hard to dismiss their arguments out of hand. If they are right, then commodity prices could continue to exert upward pressure on overall inflation for many years yet.

AUTHERS: If the Fed is missing anything so far, I think it is the extent to which inflationary expectations have already risen faster than might have been expected. We’ve had a generation of spectacularly stable inflation expectations since Paul Volcker persuaded everyone that the Fed would never allow inflation to come back. I suspect it’s easier to shake those expectations back into life than the Fed currently assumes.

For more concerning evidence of reviving inflation expectations, I’d look at the University of Michigan survey of consumers. It always overstates inflation, but the direction of travel is concerning, and the rise is hard to ignore. Since the survey started asking the question in 1987, expected inflation has only been higher than it is now during the oil price spikes of 1990 and 2008. The good news is that the Fed appears to have successfully jolted Americans out of their deflationary psychology. The risk is that they will reinstall an inflationary mindset.

Is the Fed’s choice of core PCE still the right gauge to be looking at when talking about inflation?

ABRAMOWICZ: On the question of PCE in particular, it’s a tougher metric to use in a pandemic economy. As an example, prices in hardware stores have increased quite a bit, while the cost of flights stagnated (at least until recently) as people stayed home. PCE, which looks at both services and goods price rises, won’t pick up these disparities. That said, it’s a hard measure to disregard entirely as, theoretically, the gap between services and goods inflation should narrow as the world returns to something more normal. In general, however, the investors and economists seem to be looking most closely at wage growth to determine the likely stickiness of inflation.

AUTHERS: PCE rather than CPI? It’s easy to be cynical about this because the PCE measure tends to be lower. It also doesn’t come with all the useful component data that allows us to go to town explaining the CPI each month, and it only comes out quarterly. The PCE is arguably better at the moment as it is based on the prices of what businesses are selling, rather than what consumers are buying, and because it tries to take account of changes in buying habits; if people substitute X for Y because there is a shortage of Y and its price has gone up, the PCE index will adjust to have X instead of Y. Thus, theoretically, it should not be too badly thrown by the effects of shortages and bottlenecks for individual companies’ supply chains as the economy reopens.

That was a much geekier answer than I expected to be offering, but in general I can understand why the Fed uses Core PCE as a target, and I can also understand why many people find this suspicious, or get cynical about it.

FARCHY: If we’re looking at inflation, the commodities that have the greatest impact on inflation are energy and food. On the energy side, the oil price has risen a long way from the lows of last year, but it’s still a long way below the highs of the last cycle. Demand is rebounding rapidly, meaning it could have further to go, notwithstanding the longer-term energy transition.

Asian thermal coal prices are back at historically high levels above $100 a ton. In agriculture, all the focus is on the weather: Prices have risen a long way, but if the U.S. gets the drought that some people are worrying about, they could yet rise further. But the commodities attracting the most investor optimism are ones tied to the current extreme strength in the construction and manufacturing sectors, or to expected future demand driven by the energy transition. Examples include lumber and steel (the former), lithium and cobalt (the latter), and copper and aluminum (both).

Does adjusting prices as a result of innovation -- also known as hedonic price adjustments -- in the U.S. CPI basket structurally suppress reported inflation rates?

ABRAMOWICZ: This is an argument many people make -- when they shop for food, or pay tuition, or buy a new car, everything seems much more expensive and yet the Fed-tracked measurements of inflation remain much lower than that. Some people point to hedonic price adjustments -- the idea that indexes are altered to reflect both higher intrinsic value in goods that might otherwise be seen as the same, as well as external forces like, say, a pandemic crash and violent rebound.

AUTHERS: On hedonic adjustments: The classic argument that inflation is under-stated is that the basket is wrong and that the stuff people really need is going up by more than CPI. But economists argue that this is exactly the wrong way around. It is the stuff we buy the most where there has been the most frantic activity to compete on quality as well as price, and the quality has improved so much that we are getting much better value for money.

ABRAMOWICZ: There’s a larger question here: At what point do the everyday prices people pay on the stuff they need lead to the inflation that the Fed cares about?

The answer is (surprise, surprise) tricky. If prices of staples rise too much, many households will buy less stuff, especially if their salaries don’t rise a proportionate amount. This is a dreaded outcome that gets the economy closer to a stagflationary environment, not necessarily runaway inflation on a broader level.

In my mind, a big issue is, at what point will inflation in the most commonly purchased items lead to their demanding much higher wages? This would get us closer to a more broadly inflationary environment. And it’s deeply relevant right now since the Biden administration is pushing higher minimum wages and more unionization.

Could labor costs start rising and to what extent does it need to be a structural rise for inflation to stick?

AUTHERS: Labor costs are obviously crucial to this, and they are central to the so-called Phillips Curve relationship -- that suggests there is a trade-off between inflation and unemployment. It is popular to view what happened under Paul Volcker four decades ago as the ultimate sign that there was a trade-off; the Fed was prepared to withstand very high unemployment for a few years, and crushed inflation in the process.

In practice, as I understand it, it looks as though the relationship may have been more to do with the higher rates that Volcker levied, and his success in convincing people that he would keep them high until inflation came down. The high unemployment of the early 1980s was incidental. So the Phillips Curve relationship may not be as strong as many once believed. Rereading the issue that way, the crucial question becomes: Do people believe that the Fed will allow inflation to rise? If so, they will push for higher wages (which is inflationary), and they will buy things sooner rather than later (which is inflationary).

In terms of whether labor costs have already started rising: There is plenty of evidence from surveys that companies are finding it hard to fill vacancies. That implies higher costs and upward pressure on wages. The Biden administration is the most unabashedly friendly toward unions in many decades, and this may yet lead to greater wage inflation, although it is hard to see it in the numbers as yet.

Unfortunately, the official numbers on hourly and weekly earnings are currently broken due to composition effects. It was low-paid workers who tended to lose their jobs in the lockdown, leading to a big rise in average earnings a year ago. It is the lower-paid who tend to be returning to work at present, meaning wage growth appears artificially low. Those numbers can be ignored, for now, as they plainly represent transitory effects.

The Atlanta Fed keeps a “nowcast” of wage growth for both high-skilled and low-skilled workers, and finds that both are currently enjoying year-on-year wage inflation of 3.50%. That’s somewhat above average for the low-skilled, and below average for the high-skilled; there isn’t clear and present evidence of wage inflation to date. There is logical reason to fear that that could happen.

The world economy is quite literally running low on everything. If magnitude is what sets apart 2021’s supply crunch from past disruptions, the inflationary case seems pretty clear. What’s the counterargument?

FARCHY: It’s not too difficult to construct bearish arguments about commodity markets. The current boom is thanks to the unusual situation of strong, synchronized, commodity-intensive growth around the world. People are coming out of Covid renovating their houses rather than spending on holidays, and governments are coming out of Covid spending money on infrastructure. That has been very bullish, but it can’t last forever: The tragic situation in India is affecting India’s commodity demand; and the Chinese credit cycle appears to have turned.

And on the supply side, not all commodities are in short supply. There are indeed some, like copper, with relatively constrained future production. But in oil, for example, OPEC+ is still holding millions of barrels of daily production off the market. And while I highlighted the risk of a poor U.S. crop in my last answer, the flip side is that the agricultural commodity markets have built in a significant weather premium. If the weather is fine, prices are likely to come down.

But when it comes to forecasting the next few months of commodity prices, the biggest unknown is the one at the heart of this discussion: What will policymakers do?

One reason commodity prices have been rising is because investors are ploughing money in as an inflation hedge. If the Fed takes a more hawkish stance, that trade could unwind. Likewise, the Chinese government could try to squash the commodity boom by moving more aggressively to cool the economy.

Is there a magic number on the amount of debt issuance that could make debt to GDP unsustainable? Or perhaps trigger the Fed to act in some way?

ABRAMOWICZ: I almost wish there were such a number, because it would make things so much easier! But no, there’s no magic number of debt issuance that I know of. In fact, riddle me this: As the U.S. incurs record amounts of debt, the nation’s borrowing costs have generally dropped. As a result, the servicing cost has actually gotten more sustainable for the country than during other periods in the past.

A big part of this is because the Fed has been buying a significant proportion of newly sold U.S. government debt. But that’s not the whole story.

Growth tends to be slower for countries and companies with more debt. So as the U.S. borrows more money, its economy is more likely to slow unless the cash is used for really productive endeavors. In other words, unless there’s some serious innovation, more debt can itself lead to lower sovereign borrowing costs in developed nations because it dampens potential growth and inflation.

You can insert 25 caveats to this here -- it doesn’t account for MMT; we’ve observed this during China’s rise and globalization, etc. But the point is, it’s complicated. And no, there’s no magic number.

After the global financial crisis, China had a massive infrastructure package that boosted commodity demand. Arguably, that was one trigger of inflation in the post-recessionary era. To what degree will the success of fiscal spending determine the fate of the economy? Is all fiscal spending created equal?

AUTHERS: China’s massive infrastructure package was critical in helping to lift the world out of the Great Recession, but the most important point about it was that it didn’t spark inflation. Chinese core CPI topped out at 2.5% in 2011. Metals prices, on which Jack knows more than I do, did rise a lot, but that proved transitory. After 2011, they went into a prolonged bear market.

Why we had such a lifeless non-inflationary recovery is of course one of the critical questions of the age. Certainly a big part of it is that most developed countries didn’t resort to big fiscal spending. Instead there were fears over the deficit in the U.S., David Cameron and George Osborne resorted to austerity in the U.K., and the euro zone spent the best part of a decade dealing with its sovereign debt crisis. Even in China, where the splurge of spending was financed with debt, the leadership swiftly pivoted toward attempts to rein in debt.

So I would see plenty of room for a big debt-funded splurge on infrastructure spending to make a very big difference to the developed world. It hasn’t really been tried in a long time. If it’s successful, it boosts employment and brings some inflation in its wake, and if it’s a disaster it doesn’t get many people back to work but revives inflation. The key is how productively the money is invested.

To the extent that inflationary expectations can be self-fulfilling (and they very much can), it’s interesting to see how strongly investors are currently betting that the current combination of easy monetary and fiscal policy in the U.S. is going to give us higher growth in combination with higher inflation.

I think the critical point that leads investors to make this assumption is that this time there is an alignment between fiscal and monetary policy, and there is more of an agreement between economies.

FARCHY: To me, one of the most interesting aspects of the post-Covid spending in much of the world is its focus on stimulating green technologies -- and, particularly, electric vehicles. That’s a big part of what’s driving bullishness about metals like copper, aluminum, cobalt and lithium, and what’s causing some people to be bearish oil in the medium to long term.

But from the point of view of inflation, it’s interesting because it is, in a sense, inflationary. John made the point earlier about modern iPhones being disinflationary because they’ve replaced dozens of other devices; well, for electric vehicles it’s the opposite story. We can all hope that at some point in the future EVs will be cheaper than combustion-engine cars, but for now they are significantly more expensive. That makes the coming electric vehicle revolution very unusual among technological revolutions: It involves a shift to a higher-cost technology.

So, what if this all goes wrong? Is a market fallout inevitable and what might that look like?

ABRAMOWICZ: This is a grand experiment on every level. Theoretically, much higher inflation could torpedo markets of all types that are valued on near-zero rates. Even moderately higher inflation could further dent valuations of tech stocks, SPACs, and certain areas of credit markets.

No one really knows the path this could or would take, because there’s also a feedback loop: If riskier assets start selling off, investors typically return to Treasuries, which would put a natural cap on how high benchmark yields could go. And the Fed has shown a willingness to act aggressively when put to the test. But this time could be different, with some investors abandoning traditional 60-40 investment models in preparation for stock and bond markets selling off in tandem.

To sum up, one of the biggest concerns I have is that the Fed is tethered to keeping rates close to where they are for the foreseeable future for fear of otherwise triggering a financial crisis. There’s so much debt out there, and such high equity valuations, that a significant selloff could bleed into the real economy in ways that would hurt the most vulnerable households. The Fed at a certain point is being held hostage by the market it has enabled.

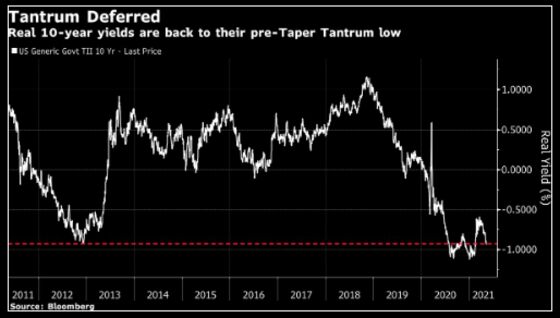

AUTHERS: This is a question about how far real yields can rise before they upset the stock market. Recent history gives us some clear guidance. At present, real yields are right down at their low from late 2012, which ended with the dramatic “taper tantrum” when then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke started talking about tapering off QE asset purchases. They can’t go much lower, and there is room for them to rise. Real yields topped just above 1% in late 2018, and that caused equity markets to freak out, and the Fed to pivot. It prompted the selloff that reached a crescendo on Dec. 24, now generally known to traders as the Christmas Eve Massacre. So it’s unlikely that real yields can get as high as 1% (historically a very low number) without prompting a spasm in the stock market. Which is alarming in itself.

FARCHY: On the commodities side, the main driver of the boom has been the very strong, synchronized global economic rebound. But there is no doubt some speculative froth, too. I don’t think a bond market wobble is likely to completely derail the rally in commodities, but it could certainly take some of that froth out of the market and so trigger a sizeable correction. All the more so if it coincides with a large U.S. corn crop, or bad news about new Covid variants.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.