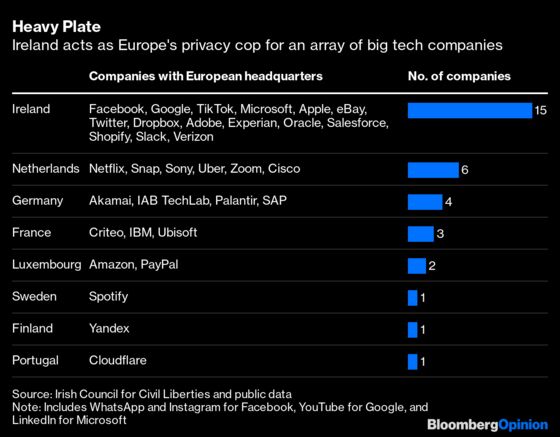

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Europe’s ambition to lead the world on data privacy has a weak spot: Ireland. The country’s Data Protection Commission works on behalf of 447 million EU citizens to defend their data from Meta Platforms Inc., Alphabet Inc. (the parent companies of Facebook and Google respectively), Microsoft Corp., Apple Inc. and roughly a dozen other tech giants — and it’s been too lax on the job.

The DPC has barely dented its casework as Europe’s main privacy enforcer, publishing decisions on about 2% of the 164 privacy cases it has taken on with “cross border” significance, according to a September study by the Irish Council for Civil Liberties, a human-rights organization. It’s had this job since Europe’s landmark General Data Protection Regulation was applied three years ago. Ireland is responsible for policing an array of large tech firms because they have based their European headquarters on its shores.

Spain has a similar budget to Ireland’s, but its privacy regulator has ploughed through 52% of its cases, while the Netherlands has completed 36%, the study adds. While Spain issues roughly two or three decisions a day, Ireland is doing two or three a year. That’s problematic when Ireland is policing so many firms with an enormous influence on society.

What gives? Helen Dixon, head of the Irish DPC, this month defended her agency’s performance to Bloomberg News, arguing that regulation is more complex than people realize and crucially, takes time. Complaints underpin cases, and the Irish agency also receives far more of these than its peers because it oversees such well-known firms, a DPC spokesman said, adding it had resolved 600 out of 1,200 cross-border complaints since 2018.

Still, the criticism bubbling up for years has recently become a chorus, and points to issues with both speed and quality of work:

- The European Court of Justice said earlier this year that the DPC showed “persistent administrative inertia” in its case work.

- The EU’s Parliament last year said it was “particularly concerned” so many privacy cases referred to Ireland had not reached the stage of a draft decision.

- Other European data-protection agencies have raised an unusually high number of objections to the agency’s decisions, with many grumbling about the piddling nature of fines, as well as the poor quality of probes and lack of documentation, according to Austrian privacy lawyer Max Schrems, who has been a thorn in the side of the Irish agency for a decade.

- Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen warned European lawmakers last month that the Irish regulator suffered from a conflict of interest because so many tech giants were based in the country.

One of the drawbacks of the EU’s vast architecture is that if a member state fails its role, another can’t take up the slack, and that has left other privacy regulators frustrated. Several activist groups, who would normally be going after Big Tech companies, are now also targeting the DPC. “It’s unprecedented,” says Schrems, who last week filed a complaint with Austria’s Office for the Prosecution of Corruption against the Irish agency.

Johnny Ryan, a senior fellow at the Irish Council for Civil Liberties, has also filed complaints about the DPC’s work. “They’re a black box,” he says. A DPC spokesman said it was obliged to keep much of its work confidential. He also declined to comment on Schrem’s complaint broadly, but stated that the agency “must balance its obligations to protect confidential information against the complainant’s and the data controller’s rights to fair procedures.”

Much of this was predictable. Ireland’s long-standing culture of low tax and low regulation attracted many large multinational companies, and that has likely weighed on the country’s ability to have checks and balances. Dixon, who was appointed to her DPC position by the Irish government in 2014, has a budget is overseen by the Irish Justice Ministry. It is not funded by fees paid by companies, as is the practice for the U.K., Spain and other countries.

Europe’s privacy watchdog needs some kind of reform. Civil litigation and complaints like Schrems’ will help, but the Irish government should also launch an independent review of the agency. It could appoint two additional commissioners to work with Dixon, people who have deeper expertise in privacy regulation and a tougher approach to tech companies. Whistleblower Haugen has proposed an even more radical option: Set up a single privacy regulator for all the EU, bringing together tech specialists spread over different national agencies.

Dixon likely never intended to give Facebook and Google an easy ride, but the system she works under makes policing them extremely difficult.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Parmy Olson is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. She previously reported for the Wall Street Journal and Forbes and is the author of "We Are Anonymous."

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.