Investors Have Deutsche Bank and Credit Suisse Upside Down

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Credit Suisse Group AG had a horrible first quarter. Deutsche Bank AG had strong revenue growth, but that was tainted by some unexpected costs.

The Swiss bank is just beginning to fix a wealth of problems, while its German rival is nearing the end of an overhaul of its assets, staff and systems. Credit Suisse is losing market share in dealmaking and trading. Deutsche Bank just had its best fixed-income trading quarter in years and is winning back clients for takeover advice.

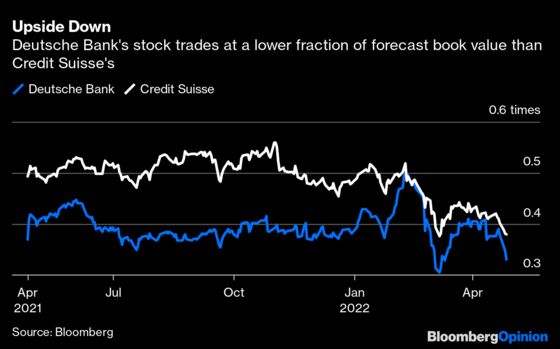

But investors still put a higher value on Credit Suisse. The German lender’s shares dropped nearly 6% on Wednesday morning, while the Swiss group’s stock was down less than 1%. This is a puzzle: Investors are changing their views on both too slowly.

Since last year, the joke is that Credit Suisse has taken Deutsche Bank’s mantle as Europe’s most dysfunctional major bank. The Swiss group’s slapdash risk management was exposed by its $5.5 billion loss on the collapse of hedge-fund-like family office Archegos, whose founder, Bill Hwang, has now been handed criminal charges in the U.S. Meanwhile, some Credit Suisse clients faced huge losses on funds invested in short-term debt managed by Greensill Capital, the failed U.K. lender.

Deutsche Bank’s problems were probably worse five or six years ago than Credit Suisse’s are now: It had more bad assets and needed a costly IT rebuild. With a lot of hard work done, Deutsche Bank now needs revenue growth to boost its profitability. Some investors are skeptical that will come.

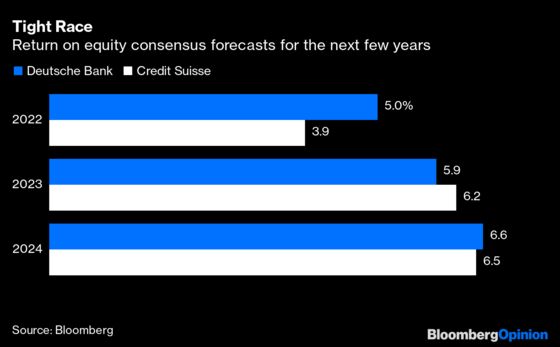

Even so, Deutsche Bank’s return on equity is forecast to be higher than Credit Suisse’s this year and in 2024, according to Bloomberg consensus data. Credit Suisse is forecast to do marginally better in 2023.

In the first quarter, Deutsche Bank did well where expected: Trading in interest rates, currencies and emerging markets gained from volatility and the wider gaps between buy and sell prices that banks can quote in such times. Its fixed-income revenue growth was bested only by Goldman Sachs in percentage terms.

On top of this, its investment in merger and acquisition bankers is bearing fruit, with fees up by nearly 90%, admittedly from a small base.

However, costs were increased by two things: Higher expected bonuses for bankers in the areas that are doing well and a big jump in the European levy for an insurance fund to cover future bank failures. The levy rose 28%, but also each division had to pay a greater share because Deutsche Bank’s bad bank has shrunk and so it takes a smaller allocation of the tax.

This cost surprise was another complicated wrinkle in Deutsche Bank’s recovery story. It shouldn’t trouble investors, but as a bank that is working to win back trust, any wobble still provokes a reaction.

At Credit Suisse, the story was simpler: It lost revenue in most businesses. Some was predictable: In the investment bank it has shut down its prime brokerage, which lends to hedge funds, while its fixed-income trading is geared towards U.S. mortgage bonds, where trading was poor for all banks. In wealth management, the weakness of Asian markets, renewed bouts of Covid and China’s common-prosperity policy to rein in billionaires and technology entrepreneurs have all taken their toll as they did for UBS AG this week.

But Credit Suisse lost more ground than expected in advisory work on takeovers, in leveraged finance for private-equity deals and in equities trading. Even accounting for the $173 million revenue lost from its closed prime brokerage, equities trading was down 30% to $545 million, a much worse performance than rivals like Morgan Stanley and UBS, where revenue rose.

Fees for dealmaking and fundraising advice were also down much more than peers — nearly 60% lower. The collapse of the SPAC-listing conveyor belt, which fed both Credit Suisse’s advisory and equities businesses, has hurt, but being so reliant on one high-risk business isn’t good.

But there’s a question too about whether the bank has the right people and incentives following several years of aggressive targets, weak risk management and the subsequent disasters. Some investors are concerned that the culture at Credit Suisse will take longer to correct than just a year or two.

Credit Suisse is also cleaning up a long list of dirty laundry in courts and negotiations, some of which has been around for more than a decade. It pre-announced nearly $700 million in litigation charges, which was expected to push it into a loss for the quarter. Ultimately, that loss turned out worse than expected because of the revenue weakness.

Investors won’t give Deutsche Bank the benefit of the doubt until it regularly produces revenue growth and keeps costs controlled. But they also don’t seem to have faced up to how much work and time might be needed to turn Credit Suisse around.

Deutsche Bank’s stock-market valuation is back down at one-third of forecast book value. Credit Suisse, while down a lot, is still at nearly 40% of forecast book value. They ought to swap places.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

- FANGs and the Euro Crash Into Crises of Expectations: John Authers

- Has the Activist-in-Chief Met His Match?: Chris Hughes

- UBS Knows This Trading Boom Won't Last Forever: Paul J. Davies

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Paul J. Davies is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering banking and finance. He previously worked for the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.