(Bloomberg Opinion) -- When it comes to financial markets, narratives are powerful things -- and often misleading. The big (and unexpected) decline in yields on longer-term U.S. Treasury securities from about 1.75% in late March to a recent 1.15% has convinced many investors that central bankers were right all along, and that the faster inflation the world is currently experiencing is merely temporary and will decelerate again when supply-chain bottlenecks caused by the pandemic have eased. The trouble is that much of the drop in yields has nothing to do with inflation and even the bit that does probably doesn’t say anything interesting about where inflation is headed.

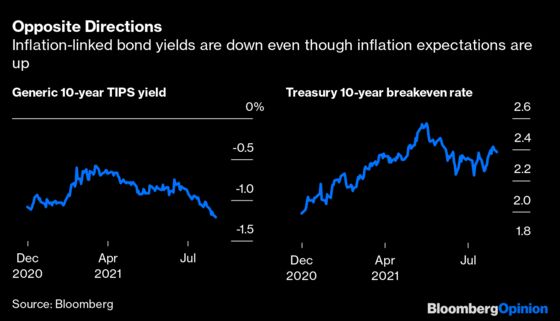

There are a number of ways to think about this. The first is that movements in bond yields don’t only reflect inflation expectations. In simple terms, the two main components of a Treasury bond’s yield are the real yield (which is what you get after accounting for inflation) and the expected rate of inflation over the life of the bond. (There is, or should be, a risk premium for both expectations being wrong, but put this aside for now.) The drop in 10-year yields the past few months reflects a decline in real yields, which you can easily see from the yield on 10-year Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, or TIPS. In mid-March, the yield on 10-year TIPS rose to a “high” of minus 0.58%, before dropping to minus 1.20%. Measures of inflation expectations, though, rose over the same period.

The drop in real yields also comes with a story that dovetails with the inflation narrative: that U.S. economic growth is slowing, thus crimping demand-led inflation pressures. Well, growth will slow, but that was always going to happen given the very strong rebound in the first half of the year. And there is a big difference between a slightly weaker growth rate, where the baton is passed from the government to the private sector, and demand screeching to a halt. Lest we forget, Democrats are in control of the government and, for better or worse, has no aversion to spending trillions of dollars more on the economy. Looked at another way, the true shocker is that the real cost of government borrowing has fallen to a record low in real terms.

Part of the answer is that one arm of the government — the central bank — has been buying bonds issued by another arm of the government — the Treasury Department. So far this year, the Federal Reserve has purchased about $490 billion of the $2.7 trillion of the Treasury’s net issuance.

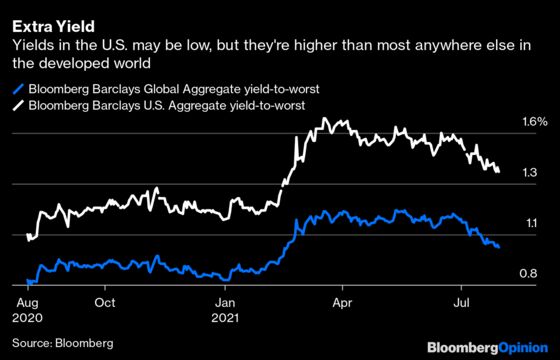

That still leaves the tidy sum of $2.2 trillion that needs to find a home, which is where the alchemy of financial markets comes into play. Even if yields in the U.S. look shockingly low, Treasuries do at least have something recognizable as a yield. Some $16 trillion of bonds globally have yields that are less than zero, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Normally, any foreign investor buying U.S. assets would have to take currency risk. But because short-term rates in the U.S. are so low and the Fed has flooded the world with dollars, foreign investors can buy U.S. Treasuries hedged into their own currencies with a huge pick up in yield compared with local alternatives, thanks to something called a cross-currency basis swap.

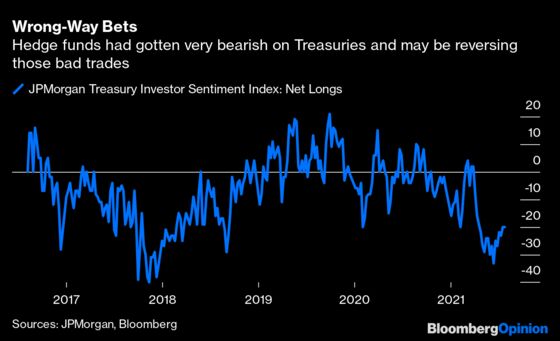

And as U.S. debt prices have rallied, the gap in yields between short- and longer-term yields has shrunk, forcing the many hedge funds who had been betting on the opposite happening to reverse those trades. This has, in effect, meant selling shorter-term bonds and buying longer-term bonds. As longer-term bonds rallied, so-called systematic funds such as commodity trading advisors and the like have jumped into the market to take advantage of the momentum, further pressuring yields lower.

Inflation expectations have barely budged in all this. Partly, I suspect, because although inflation has come in stronger than expected, the overwhelming majority of investors expect it to recede. This fits with their experience of the past 25 years, conforms to the narrative by central banks and echoes what they think (wrongly) the bond market is telling them.

Here’s the thing, though. Although used cars are a bit of an oddity, the evidence that overall inflation rates are about to fall is minimal. Import prices are still rising and are likely to rise further still judging by South Korean export prices, the bellwether of global trade prices. Prices for services prices, which accounts for some two-thirds of the economy, were rising at about 3% at last count and look set to rise further. Company inventory levels are low relative to demand, a situation that will take many quarters to solve, not a few weeks.

You shouldn’t think that markets — or central banks — have any special insight into inflation. In March of 2020, the bond market was signaling it expected an inflation rate of 0.25% in the next five years. It’s now signaling inflation of 2.7% and I strongly suspect that will go higher.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Richard Cookson was head of research and fund manager at Rubicon Fund Management. He was previously chief investment officer at Citi Private Bank and head of asset-allocation research at HSBC.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.